Editor's Note: The following is an excert from What We See, out now from Quarto Press.

I became a photojournalist around 2007 while I was a college student in New York. If I felt the yawning absence of women colleagues and mentors in the press corps at the time, I certainly did not understand how it was impacting my own growth as a photographer. But, by 2016, industry reports were starting to emerge that only 15 to 20 per cent of working news photographers were women and that major news outlets were hiring women photographers at even lower rates. And when interrogated about their assigning practices, editors frequently responded that they just did not know where to find women photographers.

In response, I launched Women Photograph in 2017, a hiring database of women and nonbinary photographers from around the world. Today, our community includes more than 1,600 independent photographers based in 110 countries. And our mission has grown alongside it. We distribute project grants, host annual skills-building workshops, run a mentorship programme that connects early career photographers with editor and photographer mentors, exhibit the work of our photographers at festivals and in galleries internationally, and collect hiring and publishing statistics on the photojournalism industry.

Our inaugural book What We See is a broad survey that represents the equally broad careers of our members. The goal is not to make any generalizations about the gaze of women and nonbinary photographers — such generalizations are impossible. The directions in which we can expand our traditional understanding of photojournalism are infinite. This book merely begins to hint at the possibilities.

Many of the photographs in this selection represent an evolution in the medium — the photographer no longer dictates the narrative. Instead, the distinction between photographer and subject morphs into a visual collaboration. In that way, reclamation here is not just for the photographer, but also for those in the photographs themselves: they are being explicitly empowered to dictate the terms and the construction of their own narrative. This makes the images even more powerful: whether through painted mythology or protective nail polish, the agency of storytelling does not belong to the photographer alone. — Daniella Zalcman

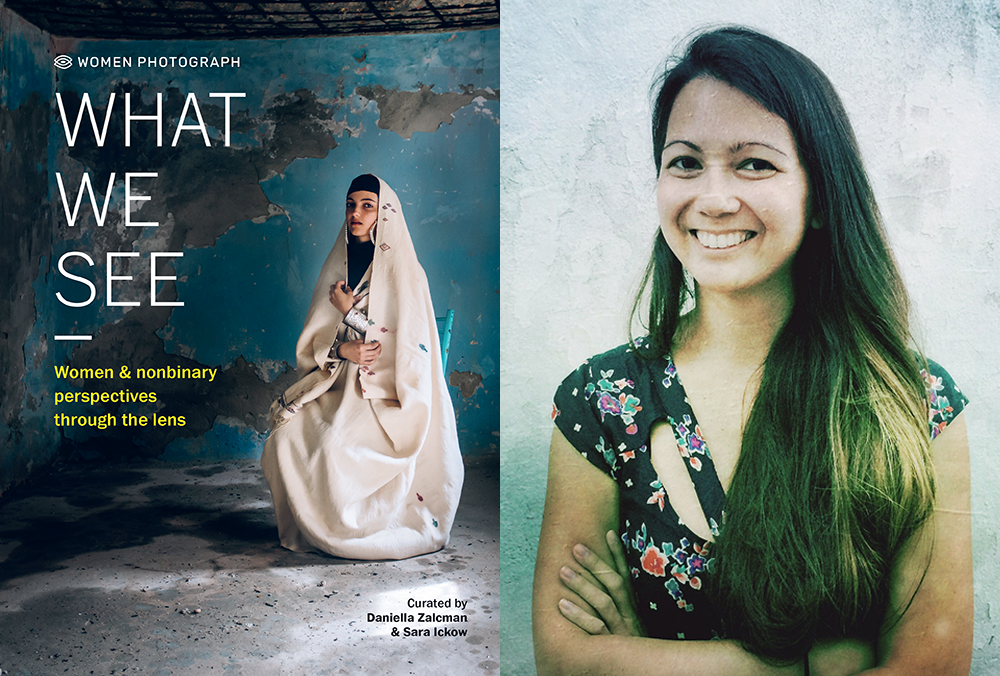

Yumna Al-Arashi, Yemeni Egyptian American

Northern Yemen (Yemen; 2013)

This work was made during my last trip to Yemen, before the ongoing conflict began in 2014. The image was part of a series of photographs that sparked conversation around the ways in which we perceive Muslim women in Western media. I felt the need to ask why Western media always portrayed Muslim women in a negative light, especially hijabi women. This portrayal used women’s bodies as a weapon of war, creating propaganda under the usual guise of ‘us’ needing to save ‘them’ from their oppressors. I believe women’s emancipation does not require women to adhere to any way of dress — whether it is hijab or bikinis. Defining emancipation based on physical appearance is not adhering to the truest form of the word. Woman’s emancipation enables a woman to have equal rights in every realm, no matter how she dresses. I sought to photograph women close to me in landscapes and poses that reflect their power. The series was a launching point for my career as a photographer and helped me start to investigate the ways images impact our notions of the world, and why it is so important that we take a critical approach to the work we both digest and produce.

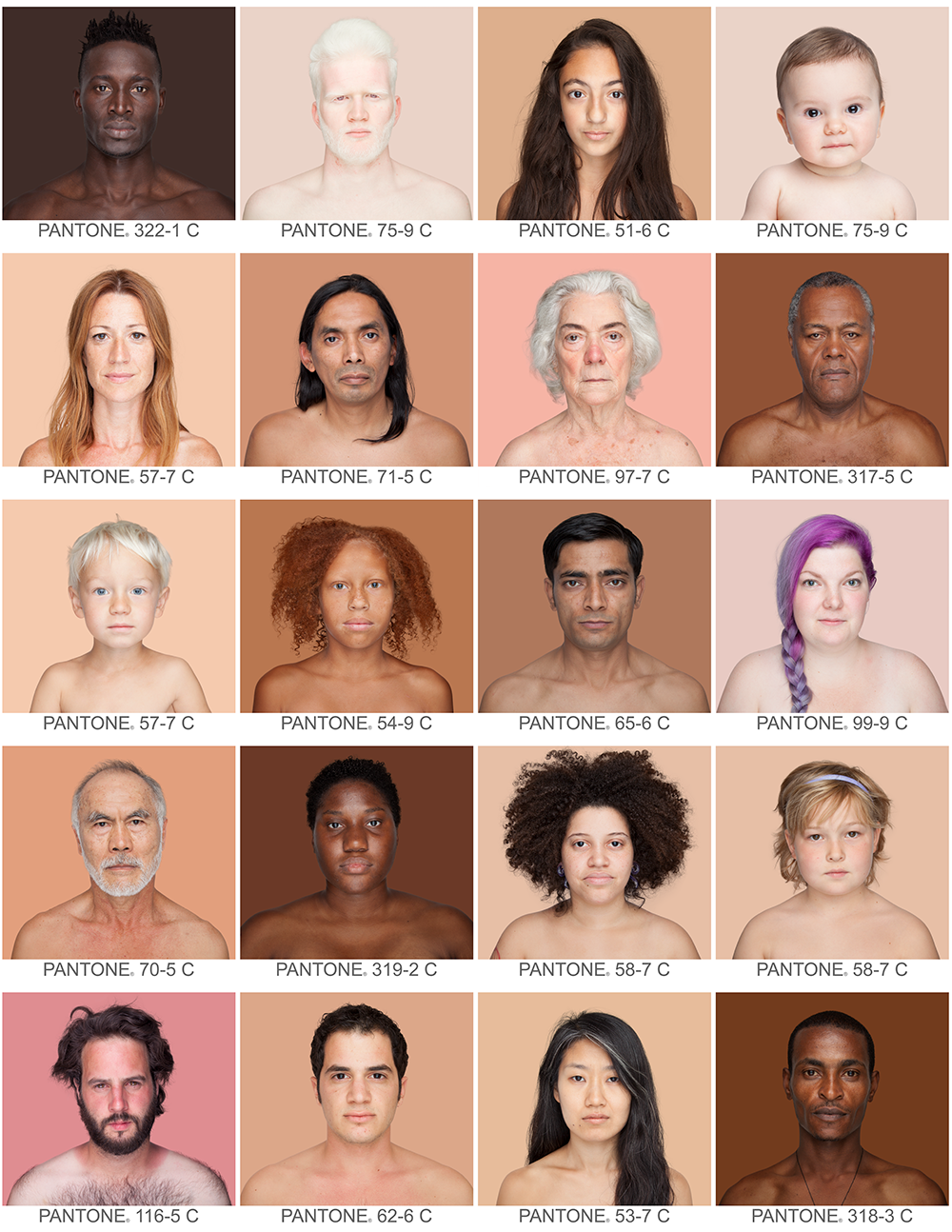

Angélica Dass, Brazilian Spanish

From the series Humanæ (Global; started 2012)

Humanæ is an ongoing reflection on skin colour, and an attempt to document humanity’s nuanced colours rather than the simplified labels ‘white’, ‘red’, ‘black’ and ‘yellow’ associated with race. It also seeks to demonstrate that what defines human beings is our inescapable uniqueness and, therefore, our diversity. The background for each portrait is tinted with a colour tone identical to a sample of 11 × 11 pixels taken from the nose of the subject and matched with the industrial Pantone palette, which, recontextualized, calls into question a spectrum of contradictions and stereotypes related to race. My practice combines photography with sociological research and public participation. I see this project as an activist undertaking, manifested especially in the direct and personal dialogue between me and the public. Humanæ’s message is fundamentally educational. I have photographed more than 4,000 volunteers so far across 20 countries and 36 cities around the world. Humanæ is a spontaneous participatory project that has no set end date; instead it acts as a catalogue of the breadth of who we are, without labels.

Yagazie Emezi, Nigerian

From the series When Did A Piece Fall Off, (London, UK; 2018)

This image is selected from When Did A Piece Fall Off, a series of p ortraits featuring a young woman on a journey of retraced steps and discovery. These images were intended to support a fictional story and allowed me to push beyond my normal space of the outdoors by using a studio provided by PDesigns Studios, in London, with a patterned set design by artist Christina Poku. I wanted to combine my usual documentary approach to photography with something soft and sensitive in regard to the model Favor and the setting. In this bid to try new things, I applied it to the story of Favor, exploring what happens when we leave the old for the new, what is left, what is taken. In addition to the use of fragmented pieces of pattern and glass to build out the story, I also tend to accompany my series with questions and short poems:

What do we leave behind when coming into ourselves?

Looking for lost selves, when did a piece fall off?

Along the way, when you broke down, what part of you did you forget to pick up as you gathered yourself again?

Erika Larsen, American

Magda, (Peru; 2018)

I met Magda during a 14-year exploration of ritual through photography. Fascinated by thoughts of transformation and regeneration, I began to contemplate healing. In time, I came to define healing as the experience of transcending suffering. I realized that healing was simultaneously a subjective encounter and an expression of humanity’s wholeness. With that in mind, I searched for people who could share primordial knowledge to help me better understand what it means to be human. This awakened a desire to document ritual, to remember that we are part of nature, and ultimately brought me to a new understanding of time. This journey took me through the Americas and into communities that are deeply intertwined with the natural environment. I met Magda at her home in San Francisco, Peru, where I had met her father and mother years before that. I returned to them several times over the next 14 years. Their daily routines revealed a profound connection to collective memory and a respect for broad interpretations of time. This image is part of my book Materia Prima, which is a collection of photographs and poems from this project and includes collaborations with artists Frida Larios and Tsista Kennedy.

Charlotte Schmitz, German

La Puente, Machala, (Ecuador; 2016)

I first heard of La Puente, one of the largest brothels in Southern Ecuador, while living in Machala as an 18-year-old exchange student. The brothel stuck in my mind as a place that symbolized the gendered double standards that exist in every society. Hyperaware of, and always bothered by, the inevitable hypocrisy surrounding one’s existence as a woman, I returned to

La Puente 10 years later to interview and photograph women sex workers, to make sense of their marginalization and misrepresentation all around the world. The majority of sex workers are women, yet most visual projects are authored by men and often fail to provide a deeper emphasis on how sex workers want to be seen. These Polaroids were created in collaboration with the women in La Puente, who chose their own poses and became part of the creative process by applying nail polish to their portraits, in some cases choosing to obscure their faces or otherwise embellish their images. When asking one woman what she was thinking while painting with nail polish on her photo she shared: ‘I was thinking that I was enhancing my beauty and covering my identity’.

Miora Rajaonary, Malagasy

Hanta (Antanimalandy, Madagascar; 2017)

Hanta, a Sakalava woman from Antanimalandy in northwest Madagascar, poses in her lamba garment. She wears the Malagasy traditional mask, the masonjoany, a powder made from the tree of the same name that grows on the western coast of Madagascar. ‘This is my favourite outfit, I feel proud and empowered when I wear it.’ My series, LAMBA, is a photographic project intended to show how the lamba, this Malagasy garment, serves as a symbol of the island’s cultural heritage, pride and tool of empowerment for Malagasy people. Although Western clothing now dominates daily fashion in Madagascar, the lamba still accompanies most people at each important step of their lives. For Malagasy women, it remains a symbol of status and cultural pride. For each picture, I used a lambahoany as a background (a printed cotton lamba typically depicting a Malagasy everyday life scene and featuring a proverb on the lower border of the design). This project, inspired by traditional African studio portraiture, is my tribute to my people, my country and my cultural heritage. As a photographer born and raised in Madagascar, I strive to find new angles and stories on cultural and environmental issues in contemporary Africa through my work.

Isadora Kosofsky, French American

Jeanie and William, (Los Angeles, California, USA; 2012)

This image is from Senior Love Triangle, my long-term photo documentary that shadows three seniors in a romantic conflict. I first met Jeanie, Will and Adina outside a retirement community in Los Angeles and felt an immediate connection to them without knowing the details of their dynamic. Will first formed a relationship with Adina. Then, he moved into another retirement home where he fell in love with Jeanie. Since Will did not want to choose between Jeanie and Adina, they formed a trio. Although there were generations separating us, I was also contending with questions about the fragility and vulnerability of intimacy and romantic connection. All of us have found ourselves in some form of love triangle, whether literally or spiritually. We carry our past loves and heartbreaks into our present relationships. While shadowing them, I experienced longing and remoteness. I have always been drawn to people who experience loneliness even among others. Jeanie, however, saw this chapter of her life as a form of liberation. She could abandon her fears and embrace her sovereignty. Their bond challenges socio-cultural norms about older adults. They break from constraints, while facing ageless desires to be seen and wanted.

Kiana Hayeri, Iranian Canadian

Mayhem, (Kabul, Afghanistan; 2021)

A girl was reunited with her mother after a bombing at Sayed Ul-Shuhada school in Kabul, Afghanistan, which occurred about a week after the Taliban’s renewed offensive that followed on from the American troop withdrawal. The mother lost a second daughter, aged 13, in the attack, which killed at least 90 people. I have lived in Kabul since 2014 and have covered too many bombings. But this one, outside a school, was probably the hardest. The day before this photo was taken, there was a triple explosion outside a school in Kabul City. Because I am a woman, I was able to enter the space without causing too much distraction. There was a humming sound – the sound of the women crying quietly — but the room was silent otherwise. At this mosque they were burying two girls who were killed the day before. The sister arrived late because she had passed out earlier that morning, so they had taken her to the hospital. The area around the school is one of the poorest areas of Kabul.

Luisa Dörr, Brazilian

The Flying Cholitas, (Outskirts of El Alto, Bolivia; 2019)

I first encountered the wrestlers while my husband was making a documentary and I saw a short clip of the cholitas in his film. I loved them immediately. Super Barrio wrestling was created in Mexico many years ago around the same time the Fighting Cholitas were born in El Alto, Bolivia. In this image, Elizabeth La Roba Corazones fights against Alicia De Las Flores at a ring in the outskirts of El Alto. In traditional Bolivian dress, the cholitas launch themselves at each other, executing perfect moves in a quest to win. What follows is part acrobatics, part theatrics. They climb the corner ropes high above the ring and ‘fly’ across the stage, like any Hollywood hero endowed with superpowers; hence their nickname. At first, I was fascinated by the skill – seeing these Indigenous women flying through the air, reclaiming the clothing their community was forced to wear as servants for Spanish occupiers. But then I saw it went beyond the ring. They are fighting for their rights, for recognition, for equality. They are fighting to put a meal on the table for their kids. They’re fighting for their lives.

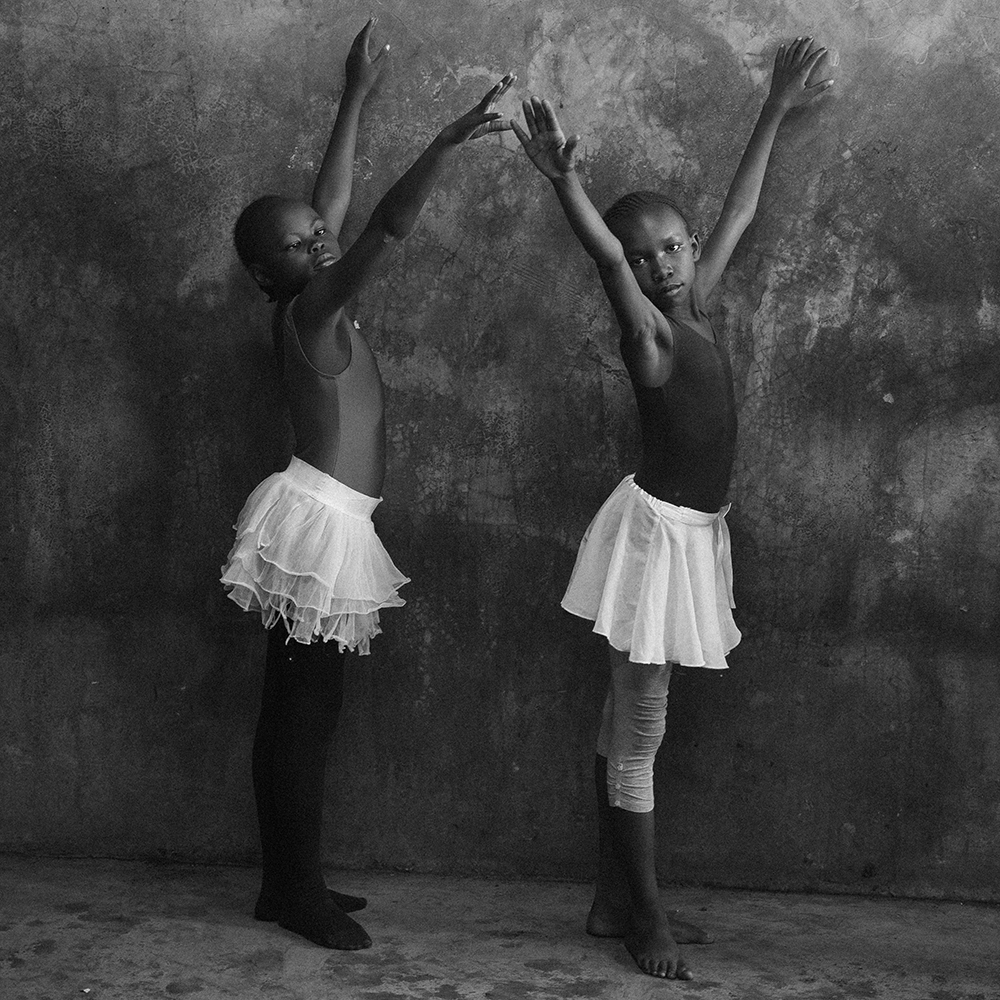

Sarah Waiswa, Ugandan

Last Act, (Nairobi, Kenya; 2017)

This image is part of my series Ballet in Kibera and was one of the first personal projects I worked on in my career as a documentary and portrait photographer. I have an interest in the intersection between identity and self-expression, particularly new African identities, and strive to highlight social issues on the continent in a contemporary and non-traditional way. I was intrigued by how ballet, often associated with privilege, was being used as a form of self-expression in one of the largest informal settlements in Nairobi. It was also interesting to me how, in that room, the children were allowed to express themselves in spite of their circumstances. I wanted to capture the in-between state of imagination and reality and offer an alternative to the monolithic stereotype of the poor African child from the slum. It was a project that told an African story without centering on poverty, but instead focused on human beings navigating their world. I worked with Annos Africa, a non-profit organization that offered the classes and initially I just watched. For me, it was an important lesson in just how important it is to spend time with your collaborators.

Kendrick Brinson, American

The Aqua Suns Get Into Costume, (Sun City, Arizona, USA; 2010)

Members of the Sun City Aqua Suns, a synchronized swim team made up of retirees, wait for their cue for a holiday reindeer routine in the pool at the Lakeview Recreation Center. Their performance was part of the Holiday Around the World celebration to mark the 50th anniversary of Sun City, America’s first retirement city that remains one of the largest in the world. Since 2009, I have been photographing the more than 40,000 residents 55 and older in this age-restricted city. My two favourite groups to photograph are the Aqua Suns, though sadly the synchronized swim team has now disbanded, and the Sun City Poms, a group of cheerleaders 55 to 89 years old. The lesson I have taken into my personal life after photographing the amazing community groups in Sun City — there are more than 100 clubs for the residents, ranging from tap dancing to pickle ball to weaving to woodworking — is to lean in to doing more creative things outside of photography. I have learned about the joy of doing things that make me feel good and that I do not necessarily have to be the best at them, or even good at them. I have watched these women rehearse and perform and I am inspired.