“Liewer bang Jan as dooie Jan.”

This Afrikaans idiom roughly (directly) translates to “Rather scared Jan than dead Jan.” It’s an expression similar to rather safe than sorry but much more urgent.

Objects designed to provide safety can still put you in life or death situations, just like their earlier, unsafer, predecessors. Many “safe” objects now bear the word “safety” as part of their (misleading) titles. Many other safety objects boldly proclaim PROTECTION, HEALTH, and SAFETY on their covers with much smaller, thankfully bold, WARNINGS and DIRECTIONS about all potential dangers on the back. But are these objects as safe as their names suggest?

The Safety Pin

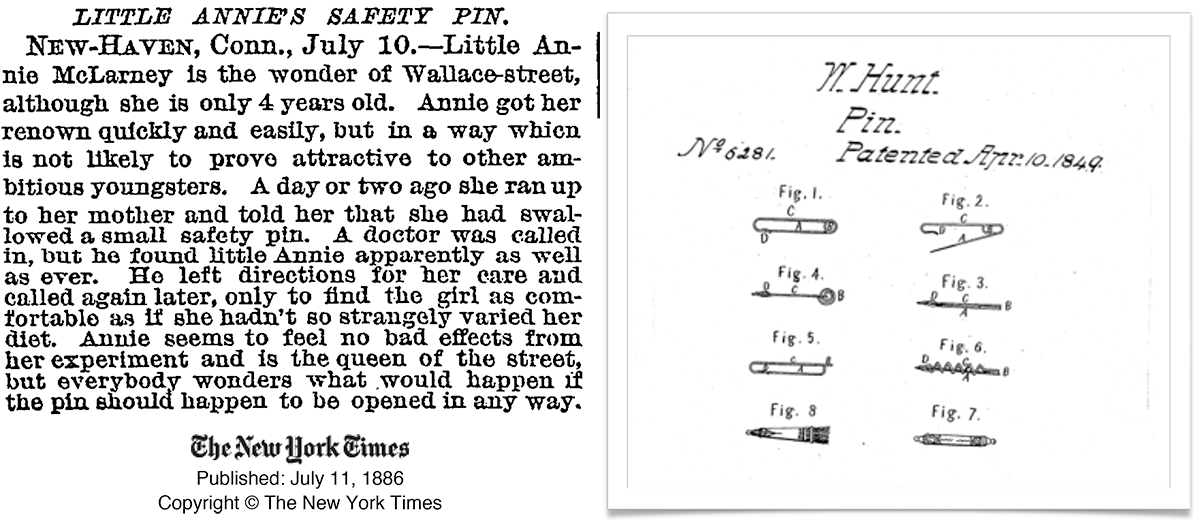

In 1886, the New York Times published an article about “Little Annie” who swallowed a safety pin. This “wonder of Wallace Street” survived the incident without any repercussions. But other children have not been as fortunate. Boye Dye, nine months old, experienced breathing complications after a safety pin became stuck in his throat, and Pearl Messler,13 months old, died soon after the removal of an ingested safety pin.

The safety pin was patented on April 10, 1859 by Walter Hunt. The patented description of the pin reads: “made from one entire piece of wire or metal, (without a joint or hinge, or any additional metal except for ornament,) forming said pin and combining with it in one and the same piece of wire, a coiled or curved spring, and a clasp or catch.”

Gene Moore, a window dresser for Tiffany’s and Co., designed a gold safety pin with diamonds in 1967. He said “It is an everyday common thing, but nobody would think of it in diamonds […] They are crazy like my windows are crazy.” Moore kept the original shape and embellishments. The basic shape and use stayed the same.

In 2016, the safety pin also became a symbol of unity for people who were against Trump and Brexit, representing safety for immigrants and refugees. Since safety isn’t always safe, “Do not swallow and do not pin onto people” could be added to the (soon to be redesigned?) safety pin packaging.

The Safety Match

Another misleading household object is safety matches. Matches allow people to light the “family gathering place” of ancient days without the tedious task of finding two perfect sticks to rub together. Creating fire through friction evolved globally. The first “real” matches were split pieces of wood tipped with sulfur that ignited when brought into contact with phosphorus. Friction matches followed, and soon after came safety matches. For safety matches, the splinters were improved only to ignite when struck against a chemical surface, allowing users to make fire without burning their hands.

Yet, safety matches still had dangerous potential. In 2014, 588 packets of Martha Stewart Safety Matches were recalled from Kmart by the Consumer Product Safety Commission on the basis that they might self-ignite, causing a fire hazard. The matches also can contain potentially lethal chemicals. One of these includes potassium chloride, the same chemical used to stop the heart in a lethal injection. “Do not swallow, lick, or chew” should be added to the permanent directions for use.

The Safety Razor

The double-edged safety razor is yet another “safety” household object, which has been revived by hipsters and shaving aficionados who believe that the cartridge razor isn’t as effective as the older safety razor. Before the replaceable safety razor, shaving was done with a straight-edged razor, which had a thick, dangerous, sharp blade. In 1901, King Gillette founded the American Safety Razor Company and in 1904 patented his “safety razor.” Though Gillette wasn’t the first to make a safety razor, he was the first to patent it and sell it as a product. Apparently the trick to a safety razor is in its angles and the only “unsafe” thing is its sharpness. So, if you practice enough, and use only as directed, you won’t cut your face.

The Electric Fence Warning

Surrounding the “safer” homes in South Africa are walls topped with spikes. Usually, if someone had a break-in or burglary, the scare of the process has them installing an electric fence. The Nemtec Electric Fence consists of many different parts that form the actual fence as well as “accessories” to help you complete your perfect fortress. By law, insurance companies have to install alert features. For an electric fence, you need at least a four-foot wall, wire, loops, bobbins, tensioners, springs, poles, at least seven types of hooks, a lightning diverter, a fence-light to indicate power status for “peace of mind,” a siren to alert you and the neighbors, strobe lights as a visual indicator of an alarm, preferably an electric motor for your gate and of course, the “DANGER: ELECTRIC FENCE” sign. This sign often shows a hand touching a wire, misinforming the reader. Key indication: Don’t touch.

Use Only as Directed

Is it a design flaw or a human flaw when people get hurt when using safety tools, equipment, gear, or objects? Perhaps the idiom “Liewer bang Jan as dooie Jan” could be changed to something a little less catchy, but something that would fit right in with the dryness and forced wording of usual safety posters: “Rather USE ONLY AS DIRECTED Jan, than dead Jan.”