A jugaad being repaired along the highway from Ajmer to Udaipur in Rajasthan. Photos: Ken Botnick

Everywhere you look in India you will find evidence of the maker’s hand. Signs painted on walls, trucks ornamented and painted with messages, cooking utensils, hand-woven and printed clothing, ritual religious objects, any number of containers made from recycled metals — even the famous jugaad vehicles cobbled together from spare parts for new lives as trucks and tractors — are just a few of the handmade objects. These articles are made with such remarkable ingenuity and embellished with such attention to detail that India could easily be considered more “high touch” than high tech. But is there anything to be learned from this intimate, hands-on, experiential culture that might be relevant to one that is becoming increasingly virtual?

An axiom popular in design circles today, “making is thinking,” implies that experiential knowledge is the most direct stimulus to innovation. The process of acquiring experiential knowledge, however, also involves an intimate relationship between the maker and his material. The maker must be familiar not only with where, when and how to source his material, but also with the best ways of giving it form. Craft culture, patronizingly referred to as “small-scale industry” by those who deal in steel and cement, is thus particularly well suited to innovation. This innovation, we argue, is the result of design thinking born from the maker’s acts of processing and shaping raw materials in his hands. We call this mode of design thinking based in the experience of craft “subtle technology.” We further propose that the Indian craftsman, faced with the demands of a population that is continually testing the limits of its resources, is uniquely placed to present us with a model for sustainability and innovation for contemporary design practice.

To the extent that a craftsman is connected to his art through personal experience, that relationship is impossible to replicate. When Indian management professionals, playing up to the current obsession with innovation, ask why they cannot seem to harness the authentically innovative spirit of the Indian streets, they fail to recognize that this kind of knowledge is by its nature unquantifiable. To draw on the ideas of the economist Friedrich Hayek, experiential knowledge is impossible to translate into statistics and cannot therefore be conveyed to any central authority in statistical form. Hayek argues that statistics are generated “precisely by abstracting from minor differences between the things, by lumping together, as resources of one kind, items which differ as regards location, quality, and other particulars.…” The process of generating statistics would thus seem to call for an elimination of the very life blood of innovation that lies in the knowledge of detail, such as only the “man on the spot” may possess. When business decides to disregard “mere detail” in the name of efficiency, it also chokes off the possibility for innovation that derives from the irreducible experientiality of artisanship.

Design might be thought of as a two-stage process, the functional and the elaborated. First, the functional requirement is fulfilled — a chair, a cup, a lamp, a sari. The process could end with the simple, usable object, but this lowest-common-denominator problem-solving is often not enough for both makers and users, who long for something more profound — an aesthetic “adjustment,” a deliberate attempt to make the functional object beautiful. This is usually done through the addition of color or the elaboration of form, both essential components of the practice of embellishment. In her book Art and Intimacy, ethologist Ellen Dissanayake calls it the process of “making special.” But as Dissanayake is careful to point out, making something special is not only making it beautiful. Positioning herself against conventional histories of humanity where the artistic impulse is considered to be a relatively late development, Dissanayake argues that, on the contrary, it was a primal impulse, located in the intimate reciprocity of the mother-child interaction. The “special” for Dissanayake thus arises equally from a transcultural desire for beauty and a basic human need for intimacy, both of which are fulfilled in the creative act of elaboration.

Elaboration connects the maker (and user) to a unique cultural context by employing shared aesthetics in color, pattern and materials, even as it enables makers to mark the object with their individual stamp, their personality — to announce to the world their role as creator. Handloomed saris from across India, for example, use modes of embellishment — colors, textures, motifs, types of weave, print or embroidery — that allow the discerning viewer to establish the object’s origins at once within a particular region of India. At the same time, each handloomed sari is one of a kind, allowing the weaver to claim it as a special creation. To the extent that the wearer is conscious of its unique quality, the buying of a sari might be thought of as the currency of intimacy between the maker and user, the mark of the maker’s hand representing almost a personal gesture for the owner.

Since raw material is usually expensive, the craftsman must know how to make the most of what he’s got. This often brings to the fore his economical genius for gathering, managing and storing materials. It is only through working the material repeatedly that the craftsman becomes familiar with its properties well enough to coax it into shape. But while we see the craftsman’s contribution as his genius for forming material, we rarely give him credit for more abstract design thinking about the broad implications of his creation.

One striking example of this is found in the unstitched garments of India, the sari and lunghi. The genius of these garments is in their simplicity; rectangles that wrap the body in a variety of ways, saris and lunghis defy changes in size and body shape. Because they are not elaborately shaped as western apparel is, they are endlessly adaptable, and certain classic textiles remain in style year after year. The simplicity of the sari’s shape also gives rise to a spectacular variety in designs of the textile itself, inviting infinite elaboration of color and pattern as invented by the textile weavers, printers and dyers. The rectangle further invites adaptive reuse once it is too threadbare to be worn as a sari any longer. Across India, old saris find new lives as pillows, pouches, ropes, lightweight blankets, hammocks for babies and more. They are even used as fences in Rajasthan. Such applications would be impossible if the original design were not so ingeniously simple, so functionally pure. A new sari would hold the wind too well to be a useful fence, and if its shape were more complex, its afterlife would be limited to ragstock. The sari, therefore, in its simplicity represents a mode of design thinking grounded in adaptability, innovation and sustainability based in craft that is distinctively Indian.

Sari fence in Rajasthan

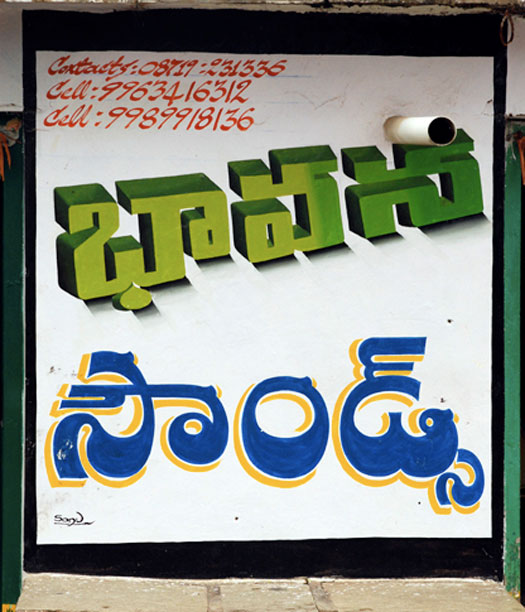

If saris and lunghis point to the collective genius of Indian design, then hand-painted signs on the streets of India suggest a more individualized agency. Hand lettering follows much of the same pattern of other craft areas but with a wholly different outcome, in that it doesn’t produce a useable object. The flowering of signs and symbols points us to a universe of concrete language. The sign painters are amazingly adaptive as they explore new ways of creating familiar letterforms in a bid to capture the client’s eye and stand out in the crowd.

For this sign displayed in Parvathagiri, Andhra Pradesh, the painter used a combination of approaches to depth that result in a surprisingly fresh composition

This underwear sign presents an example of innovative thinking about space. Finding a drain opening in the path of his endeavors, the artist spontaneously incorporated a navel (and home for a mynah bird)

Indian sign painters have long used graphic devices to give their work a three-dimensional quality, as if to produce an illusion of space that is deeper than the board on which the words are painted. This tendency might be considered a shared aesthetic among sign painters, a cultural norm. To render a letter with the illusion of depth is not as simple as it looks, but can be accomplished only with knowledge of certain attributes of visual depth perception.

Decorated dung huts in Rajasthan

Embellishment is not only a means of celebrating life. Sometimes it is also an act of defiance in the face of finitude. The exterior surfaces of dung huts (known as batoda in Rajasthani) are decorated by the women who own them as a means of claiming them publicly as possessions and expressing pride in their beauty and neatness compared to those of their neighbors. Could it be that even the humblest of things — a heap of dung that will soon end up as fuel in the fire — is worthy of the extra time it takes to elaborate its existence, to celebrate it? The maker of the batoda doesn’t usually have the luxury of time, yet she finds the time to make her work special, to take it beyond the realm of the ordinary and the unadorned.

Even the sides of the bucket attached to this massive backhoe have been decorated with welded strips of metal. A repair job or pure aesthetic adventure?

In conclusion, on India’s streets, the act of making functional things — cups, chairs, signs, books — is creativity at its most direct expression; meeting a need. Embellishing that object, making it special, requires that the maker take time with the thing to ask more questions, not only about its function, but also about the person who will use it, and about how to distinguish that object from the universe of things that surround it. Embellishing is the way we identify the object as part of a larger cultural tradition, through colors, symbols, patterns, or even language. It is what takes a generic, functional article and places it firmly in a larger cultural reference. It simultaneously makes the object more reflective of the maker’s distinct personality and brings it into the shared cultural values of beauty and function. Embellishment delights because it surprises. It is found in completely unsuspecting places, like the bucket of a backhoe. It takes ordinariness and celebrates it as if to say, “Hah! You didn’t find this beautiful, this lump of dung, but here it is and it is beautiful.” Embellishment, like adaptation, is an act of claiming agency that marks the agent as both an individual and part of a community.

Note: The authors are indebted to Ellen Dissanayake for her influential work on the origins of artistic practice.

Comments [20]

05.24.10

03:21

The amazing thing about Indian design, and the way Indians interact with objects is the blurred line between maker and user. In a sense, everyone is a maker, because everyone engages with material, adds to it, and claims agency. So yes, embellishment marks the maker as part of a community, but also marks the material as the maker's and as the community's. The lines of power, and rights, are only fluidly marked, and anyone may adapt and embellish.

The particular images you have chosen are, of course, brilliant! Love the backhoe!!

05.24.10

05:54

05.24.10

11:21

05.25.10

08:37

05.25.10

10:44

05.26.10

10:45

05.27.10

12:35

Yes. Indians retain their claim to native arts. Why? Perhaps it has to do with poverty. Or with an agriculture that still depends in large part on the hands of individuals seeking to feed their own families.

Here in America, we once had a claim to a similar birthright. Our forebears made things, often beautifully, from what they had. Some people still do, and their work is equally beautiful, innovative, appropriate. But we seem to have happily traded such beauties for a mess of pottage from Walmart (our largest private employer). It seems to me that we have traded art for "design."

In the previous century, Ananda Coomaraswamy interpreted Indian arts to the west, but not at all in terms of design. He said that "The basic error in what we have called the illusion of culture is the assumption that art is something to be done by a special kind of man, and particularly that kind of man whom we call a genius. In direct opposition to this is the normal and humane view that art is simply the right way of making things, whether symphonies or airplanes.

"Manufacture is for use and not for profit. The artist is not a special kind of man, but every man who is not an artist in some field, every man without a vocation, is an idler. The kind of artist that a man should be, carpenter, painter, lawyer, farmer, or priest, is determined by his own nature, in other words by his nativity. No man has a right to any social status who is not an artist."

Art, at least according to its original meanings, as a way of fitting things together, requires manufacture (handwork) for the purpose of use by yet other hands. To make things that will be of real use to others is a vocation, a calling that can be measured only by the joy and gratitude of those who participate. Design, on the other hand, as commonly practiced, is an adjunct of machine industry, and largely defined by the language of advertising and marketing. It serves primarily to expand consumption and can be measured only in imaginary numbers of non-nutritive dollars.

Indeed, what we must admit, if not learn, is that "virtual" culture is no culture at all; true art requires true men and women who work with the materials at hand, to serve and to feed neighbors that they know.

05.28.10

12:41

Loved the section on the design marvel of the sari and the lunghi!

Thanks for writing it so well too.

05.28.10

07:32

05.29.10

08:58

Also, the aspect of individuality that is expressed through embellishments is very much prevalent here too as much it is anywhere else in the world.

Thanks for the lovely article.

05.30.10

05:09

It is only since the onset of mass manufacturing that we have depersonalized the sense of well being that accompanies "making." The British and Americans still possessed it until about 1850-1900, and people like Wm. Morris attempted to revive it, but it is now like a mutated gene. Putting technology back in its bottle will prove as challenging as reversing the environmental degradation that results from it.

There is hope that awareness of the condition as it exists in places like India might help us. But the citizens of the so-called "advanced societies" will first need to temper their remote sensory habits by getting their hands a little dirty.

Thanks for your insights.

http://design-altruism-project.org

05.30.10

07:35

''Yes. Indians retain their claim to native arts. Why? Perhaps it has to do with poverty. Or with an agriculture that still depends in large part on the hands of individuals seeking to feed their own families.''

You are wrong here, poverty has nothing to do with art. Art has been part of indian culture or tradition through every respect, whether it is festivals,utensils, clothes, food,etc, for 1000's of years. Unfortunately goverment efforts are still not enough to protect such art and artisans of the country. Every 500 km in india the art varies, which is vivid and beautiful. This artisans can easily give up their art and look for other work, but as I said it is part of tradition, culture and so they will keep art alive even if they do anything else. Hats off to them that they are keeping such a rich heritage alive.

India is a argriculture country, which has been prime factor in Indian development and will remain so. Indiviuals you are talking about are farmers and they are proud owner of the their land. Many farmers have their sons and daughters as engineers and doctors, so it is not somebody is forced but it is about the choice.

05.30.10

07:55

05.30.10

09:49

05.31.10

06:14

I hope the authors, Ken Botnick and Ira Raja, will consider expanding this piece into something broader and deeper.

06.03.10

01:14

06.04.10

01:40

I believe though, that poverty does play a role. As long as there remains such a huge surplus of cheap manual labor (including artisans), there will be little incentive to shift to an industrial, mass produced version. This is as true of washing machines (one of which remains lovingly unused under a cloth in mother's courtyard), which are more expensive and irregular to run (given the vagaries in water and bijli) than the reliable dhobi to employ; similarly, it is true of the sign-maker, whose artful labor remains cheaper than investing in an off-set printer capable of banner-size posters.

This is not to negate the love for and skill in making art, just to say that yes, indeed, poverty is a factor in this scenario.

06.22.10

01:40

07.01.10

07:50

http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/abs/10.1162/074793605774597497

07.18.10

12:42