George C Boeree, "Gestalt Psychology," 2000

In an interview with Adrian Shaunessey, the legendary graphic designer Peter Saville once mentioned something valuable he learned ten years into his career: that there is so much more to design than “just designing.”

Just designing? Just designing? As a design student graduating nearly thirty years ago, I would have been stunned to hear this. Designing was everything to me. I had just spent five years in design school. I had entered college as someone who could do a nice pencil drawing of a bowl of fruit. I spent the next sixty months moving shapes around on grids, manipulating squares of colored paper, resolving compositions, drawing letterforms, learning the difference between Helvetica and Univers and between Herbert Bayer and Herbert Matter, redrawing a logo a hundred times until it was perfect, calculating the column lengths of Garamond set 12/13 on a 35 pica measure, and — for this was the point of it all — learning the difference between good design and bad design. When I graduated, my goal was to work with all my heart to create to former and avoid — nay, obliterate from the face of the earth — the latter. And now I learn that not everything’s about designing? What else is there?

But it’s true. I spent five years transforming myself into a designer. But what had I been before? That’s simple: I had been a regular person, like most other people in the world. And, as it turns out, it’s those people who actually make it possible — or difficult, or impossible, depending — for designers to do their work. And Saville was right: most of that work isn’t about designing.

This is the secret of success. If you want to be a designer, no matter how compelling your personal vision or how all-consuming your commitment, you need other people in order to practice your craft. Not all projects need clients, of course. But unless you’re independently wealthy, you’ll need to finance the production of your work. This means persuading people to hire you, whether it’s bosses at first, or, once you’re on your own, clients. And people always have a choice. They can hire you or they can hire someone else. How can you get them to hire you? A good question, and although it has nothing to do with actually doing design work, you’ll need an answer for it if you ever intend to actually do any design work.

Once you’re doing design work, you face another challenge: how do you get someone else to approve the work you’ve created and permit it to get out into the world? But, you might protest, certainly they’ll recognize good design work when they see it! After all, you do, and your classmates did, and your teachers did. Ah, but that was in the rarified world of design school. You are now back in the world of regular people. And regular people require patience, diplomacy, tact, bullshit and very occasionally brute force to recognize good design, or, failing that, to trust that you can recognize it on their behalf. Again, this is hard work, and work that, strictly speaking, has nothing to do with designing.

Finally, once your work is approved, your challenge is to get it made. This may mean working with collaborators like writers, illustrators, photographers, type designers, printers, fabricators, manufacturers and distributors. It also means working with people who may not care about design, but who care passionately about budgets and deadlines. Then the whole process starts again. In some ways it gets easier each time. In other ways it’s always the same.

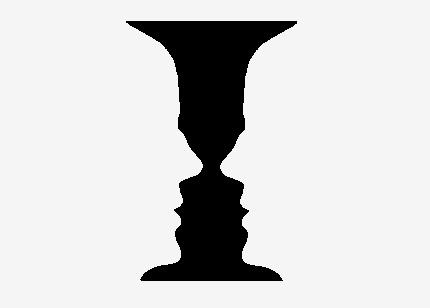

I remember a lesson from my first year of design school, a series of exercises that we did to learn about the figure / ground relationship, the relationship between the thing that’s the subject of a visual composition and the area that surrounds it. For me, this is one of the most magical things about graphic design. It’s the idea that the spaces between the letterforms are as important as the letters themselves, that the empty space in a layout isn’t really empty at all but as filled with tension, potential and excitement. I learned you ignore the white space at your peril.

In many ways, the lesson of success in design is the same, and it’s a lesson that every great designer has learned one way or another. Designing is the most important thing, but it’s not the only thing. All of the other things a designer does are important too, and you have to do them with intelligence, enthusiasm, dedication, and love. Together, those things create the background that makes the work meaningful, and, when you do them right, that makes the work good.

This essay has been adapted from the foreword to Graphic Design: A User's Manual by Adrian Shaunessey, published this month by Lawrence King.

Comments [25]

10.05.09

10:23

Thats it!

:D

(oh and I didn't know how to persuade Michael Bierut to see my blog, which is http://byfk8644.blogspot.com/)

10.05.09

10:51

10.05.09

11:43

I love the last paragraph. You almost made me cry.

I'm twitting this article :)

10.05.09

11:45

Maxim #1:

Concept is everything.

Maxim #2:

Execution is everything.

Maxim #3:

#1 and #2 may be everything, but they're not the only thing.

10.05.09

12:27

10.05.09

01:13

10.05.09

10:44

10.06.09

12:57

10.06.09

01:32

10.06.09

08:19

10.06.09

02:18

Only if you assume that designers are superior to regular people. I do not.

10.06.09

03:06

T H A N just designing.

1 9 9 0

So you and Peter Saville became partners at Pentagram the same year. Peter was in the London office and you were in New York. Peter had the shortest stay at Pentagram and you have had the longest. Peter maintained that what he learned in this time at Pentagram has been useful to him every day since then. He said this in an interview with Adrian Shaunessey.

What did Peter learn at Pentagram?

Did you work with Peter on any projects during the two years he was at Pentagram?

10.06.09

10:18

Nor do I Michael. But, for me, your essay still creates a different impression. I'm not even sure what you mean by "regular people," except that it seems to be everyone who has not gone through the rarefied world of design school (a process which transformed you from a regular person into a Designer). "Regular People" just seems belittling and patronizing, esp. when you state that they "require . . . bullshit and very occasionally brute force" to recognize good design. I don't think employing bullshit to persuade/convince our clients--whom I presume fall into your "regular people" group--is ever a good idea. It makes me sad to hear leaders in our profession assert that this is what regular people/clients "require." It comes off as being, well, rather superior. If they can't recognize good design, we'll just bullshit 'em. Nice! I'm sure this sense of superiority is not what you intend to convey, but that's how it reads to me.

10.06.09

10:48

10.06.09

11:33

It's impossible to know a little of everything. But I was wondering after hearing that, what kind of job forces you to know more than your field. If a banker has a client who is a carpenter, the banker doesn't have to know carpentry to give the guy's service. But there are jobs that force you to understand your client and figure out their needs and try to find a solution to their problem. Off the top of my head, the jobs that require you to know about many different fields, probably journalists and writers, personal assistance, police detective, priest, and to a certain degree a lawyer.

I think designer is one of those jobs. I spent the last few years designing logos, posters, and motion graphic design. But when I do them I can't just research other designs. If I was asked to do a logo of a hotel, I don't go around looking at other hotels for ideas. I mean I do look at others, but I don't think designs of others should have too much of an impact on my design.

Just for design projects, I find myself researching oil companies, political situation around the world, soft drink, eastern philosophy, zoo, railroad, jazz music, medieval history, food, Japanese culture, and so much more. And all that was just to come up with a logo or a poster. But you can't design if you don't know about what you are designing. And it is very rare that you design for design community, so you have to know more than design, always.

With just knowledge about typography and composition and without any knowledge of anything else, I don't think it's possible to design anything.

10.07.09

08:01

Here is to white space; those who understand it, who can explain it, and who can appreciate it.

10.07.09

07:59

_people require patience, diplomacy, tact, bullshit and very occasionally brute force to recognize good design, or, failing that, to trust that you can recognize it on their behalf._

Insightful and honest!

10.08.09

03:21

Carl, It was great being partners, even briefly, with Peter Saville. He has a really remarkable mind and I learned a lot from him. However, I was much more influenced by Josef Muller-Brockmann and Ed Ruscha. I divulge the sources and more in this essay:

http://observatory.designobserver.com/entry.html?entry=3557

10.09.09

07:35

Thank you for this. As always, inspiring, and oh so true. It's all about those spaces in between...

10.12.09

07:57

Of course designers are superior to regular people.

That's why we spend eighty percent of our time convincing regular people that we are superior to them.

If they would just accept it, we wouldn't have to spend so much time on it.

Good job Michael.

10.19.09

12:09

It seems that convincing people that what they want is not always best (in terms of design) is a task that requires balance or you may offend your own client.

We were once like them, before we knew that (graphic) design was more than making things 'look cool.'

10.20.09

04:22

10.27.09

01:18

Stated by Indian philosopher Nāgārjuna

Now when i look into a blank canvass, in those white spaces i dont just see emptiness, I see art waiting to be created by my hands as in the void exists everything that has yet to be created.

Stan Peter

Logo Designer

11.30.09

01:28

OR

ORDER

09.26.10

12:15