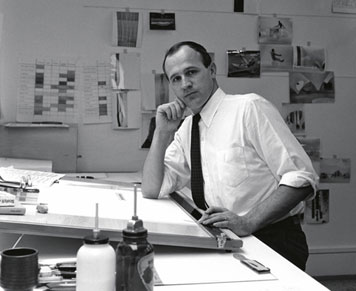

Peter Seitz in the design studio at the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, circa 1965

Having spent my professional life (thus far) working neither on the East Coast nor the West Coast of the U.S., but in what is euphemistically dubbed the fly-over zone, I've taken a particular interest in the history of graphic design in decentralized locales. Raised and educated in the Midwest during the 1980s, I can still remember the first Print regional annual (1981) and how odd it seemed not being in the "center" of things. I've always taken pride and pleasure in operating outside of official centers — New York City in particular — but am still struck by people's disbelief that "interesting work can happen there?" "There" being a relative term, a kind of free-floating non-place. Lorraine Wild, a product of Detroit (well Canada too, but the part near Detroit) captured this incongruity when she once described Cranbrook as a hot-house of avant-garde design flourishing in a rust belt.

This collision of progress and regression in one and same place embodies a kind of geographic oxymoron. It's a sensation that's been piqued again by a string of events over the last few years — little forays into the hinterlands trying to piece together how design had happened to be there — which have recently caught my attention.

A few years ago a friend of mine, Jim Sholly of Commercial Artisan, produced a sweet little booklet about his in-laws — Gene and Jackie Lacy, a husband-and-wife graphic design and illustration team practicing in Indianapolis, Indiana. Having lived and studied in this city, I was aware of the Lacys but was surprised nevertheless by the fact that not only had this publication been produced, it had been freely and widely distributed. A letter attached to the mailing offered a glimmer of insight: Gene and Jackie Lacy worked as graphic designers, illustrators and artists in Indianapolis from the 1950s through the 1990s — four decades spent creating a substantial body of work that, with few exceptions, remains virtually unknown outside a small group of family and friends. ... The Lacys were not widely known beyond Indianapolis and like so many of their contemporaries, may never be recognized for their contributions to graphic design. Hopefully, this modest mailing goes some distance to rectify that oversight. Although numerous graphic design magazines regularly profile contemporary designers and their predecessors, I am unaware of any national or regional efforts to document and preserve the work of people like the Lacys. In many cases this lesser known work is vanishing bit by bit every day.

As a designer, I was immediately drawn to this project and to the larger questions it raises. Who counts as history? Where are we looking for this history? And how once located, do we "preserve" it? While the history of graphic design is not limited to the stories of its practitioners, the work of expanding the canon, designer by designer, remains largely incomplete. It is rare to encounter a newly unearthed designer and remains, to date, far more common to see new interpretations of established figures. Although there are multiple reasons for this, I believe that one of the major difficulties is attributable to the very complicated, typically unpaid, and deeply investigative nature of such primary research. Such effort entails hundreds of hours of painstaking fact-finding, trying to locate actual examples of work, tracking down former colleagues, and, when available, gaining the trust of (and access to) a living subject's archives and recollections — all of which require negotiating complexities both personal and professional. Such projects, as rare as they are (and typically without bankable widespread interest) almost always come about as labors of love, and their success hinges on the good will and enthusiasm that comes from spouses, family members, former colleagues, students, and business partners.

For the last several years, Kathy McCoy has been documenting and chronicling the history of graphic design education programs in the U.S. — an historical niche market — first with Rob Roy Kelly at the Kansas City Art Institute and later with Ken Hiebert at the Philadelphia College of Art (now The University of the Arts). Tracing this history and its linkages reminds us that graphic design education was, in those early years, the byproduct of a European strain of modernism in the United States, and indeed, this was a characteristic of both of these programs. Yet while its location on the East Coast made PCA a natural place for a design program, the idea of a transplanted modernism taking root in the Kansas plains (or the plains of the Upper Midwest for that matter) always begs for an explanation: why there, why then, and finally, how did this come about?

McCoy's research struck me as yet another kind of history that is quickly evaporating as faculty members retire or entire programs vanish. I was more than eager to participate in a parallel endeavor, and was granted my chance this past summer, when the Minneapolis College of Art and Design (MCAD) approached me about shepherding a book project to document the work and contributions of Peter Seitz.

Seitz arrived in Minneapolis in 1964 to become a designer, editor and curator at the Walker Art Center, a position I would occupy more than thirty years later. Educated in the legendary, radical design program in Ulm, Germany, Peter ventured to the United States in 1959 to obtain his graduate degree from Yale University. After the Walker, he went on to establish several successful design studios in Minneapolis, including probably the first truly multidisciplinary, collaborative design studio in the U.S., appropriately called InterDesign. He then taught for more than thirty years at MCAD, during which time he championed the use of the computer to help solve design problems as early as the 1960s.

Such details are essential in order to reconstruct a sense of how modern design might have arrived in Minnesota. Rob Roy Kelly, who had worked at the Walker before Seitz, had been teaching at MCAD (where he was the first to use the term "graphic design" to designate the curriculum) before going to Kansas City. Once there, Kelly was the first to bring graduates of the design program in Basel, Switzerland, to teach with him — including Inge Druckrey and Hans Allemann, both of whom would later end up at The Philadelphia College of Art. Piecing together these important individual stories begins to construct a fuller history of our discipline, and its points of convergence and divergence. It is this process of connecting the dots that allows us to avoid the lone heroicism of much design history, and by expanding our attention to the whole we can begin to understand the interconnected nature of design's past, present and future.

Because this history is gradually vanishing, there is a renewed sense of urgency in documenting the lives of those graphic designers who were so influential in the formation and maturation of the field in their respective cities. Hopefully, projects like these will help to create something greater than the sum of their individual parts, by providing answers to more widespread historical questions: how, for example, did modern graphic design spread across the central United States? Such answers contribute significantly to a more substantial picture of graphic design history, by focusing long-overdue attention on those so-called local practitioners — people whose work helped pave the way for all of us. This is not necessarily about writing History with a capital "H," but about identifying an alternative history — a history from below. While no less legitimate, such histories would refer more specifically to the grass-roots nature of the work, and to its decentralized locations, its oral histories and its many marginalized subjects. It is a term and concept that should be embraced rather than shunned, because the groundwork of history and the field it supports has its foundation in this very metaphor. While the story of Peter Seitz provides one example, we can rest assured that there are many more stories just like his in cities across the country — modernism in the fly-over zone, if you will — which add a critical human dimension to design's rich cultural heritage.

Andrew Blauvelt is design director and curator of architecture and design at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis. A practicing designer, he also writes about the history, theory, and criticism of design for a variety of publications.

Comments [30]

11.15.07

12:17

11.15.07

02:05

I am from Colorado and have to say that the situation is nearly Identical as you talk about. There are no huge multi-national firms, barley 3 actual studios but lots of little mom and pop design shops. I wish that they got more recognition than they do because some of the work is fantastic.

I am a student now in San Francisco and being unknown and un-important always worried me. I want to make a difference but don't want to sell out to the "title" either. I guess it's just one foot at a time and try to make the best of yourself and your surroundings.

Cheers

11.15.07

02:42

BTW... the book is beautiful, mine just arrived in the mail today.

11.15.07

03:10

By the time I came to study in Minneapolis this area was already — I guess I could say, "back on the map". To be in that time, in this area when so much great unrecognized work was being produced is hard to grasp.

11.15.07

03:55

Many of the DO comments lately have pointed to the question of history/identity/tradition as it relates to a (graphic) design community, so this sort of work is worthwhile and relevant.

11.15.07

05:08

11.15.07

05:52

11.15.07

08:59

Thanks for a wonderful reminder that not everything that's fab comes from only one (very ego-centric!) place.

11.15.07

10:45

New York is America's business hub. 911 has yet to change that.

11.16.07

12:12

11.16.07

12:16

I enjoyed seeing the works of Peter Seitz.

11.16.07

01:01

As Blauvelt points out, the lack of resources to support proper primary research and documentation of contemporary design, not only in the hinterlands, but everywhere, unfortunately levels the field for designers no matter where they practice. This situation truly threatens to truncate the story of design in the U.S. The exisiting initiatives such as those sponsored by the AIGA are admirable but still under-funded, and under-conceptualized. The only issue I have with Andrew Blauvelt in this beautiful essay is his use of the term "alternative" histories to describe projects such as his research on Seitz, Jim Sholly's work on the Lacys, and Kathy Mccoy's project on the Swiss programs in the U.S..There's nothing "alt" about these stories: they are the stories, and we need to gather as many of them as we can before they dematerialize.

11.16.07

01:48

Finding fine lines in the hinterlands comes as no surprise to me -- I'm always struck whenever I pay return visits from Philadelphia, where I now live, by how much more deeply good visual design is woven into everyday life throughout the Twin Cities. The contrast seems particularly stark when it comes to visual identity. I sometimes wonder whether organizations based in the so-called "flyover zone" are quicker to grasp the need for something more than simple, old-boy name recognition to reinforce the image they wish to project.

(Speaking of local design histories, the last time I dropped by the Walker, I saw nothing but a grassy knoll where Ralph Rapson's original Guthrie structure once stood. That Guthrie poster brought back the same catch in my throat.)

11.16.07

06:26

11.17.07

02:01

Since moving to Kansas City I have discovered a wealth of really brilliant firms and designers. Going to school in NY was great, but we were preached to about European and east coast, US design. There was never any mention of the midwest (almost as if it didn't exist).

Thank you for this article, as I'm sure it will be enlightening to those that have grown up, studied and now work on the east coast.

11.17.07

10:18

1.There is something to be said for local design, (Toledo)

2.Those who may have drifted into the past may one day have an opportunity to shine in the future.

-cfair

11.18.07

08:07

For a long time I worried about having everything perfectly together in attempting a project like this, but I finally came to terms with the fact that you simply have to move forward and start. History is a process of constant refinement and detail, but you have to begin somewhere. One of my favorite saying is "that you make the path by walking."

11.19.07

12:45

11.19.07

10:28

11.20.07

10:00

11.20.07

03:45

Having an historic context to work in made design an exhilarating experience. Having the ability to draw on the lives and work of those who pioneered the field of graphic design gave the whole process meaning and direction.

Living here in the rust belt, as mentioned in the article, one must find inspiration from any and all historical and contemporary sources, including local peers. As Andrew so adroitly points out, there are creative people everywhere. Not only in major metropolises, but wherever design is needed and called for.

11.21.07

02:42

11.24.07

01:13

I never knew there was a Bermuda Triangle in the design world coming from Detroit with an east cost family and a west cost fiancé. I guess I am in the dark here. I have, however, noticed a similar quandary within the small world of single collegiate institutions.

I think it is strange to note that although you (as a designer) have a few different graphic design professors they do not frequently communicate with each other. I'd like to think that each professor was hired to bring a different dynamic and teaching style to the table to give provide a well-rounded program within the design department but is it wasted a bit just because of a lack of communication?

I have brought in articles and shared (what I view as) well designed work with my professors on individual basis'. I am disappointed that I rarely see anything shared between them or around the design community within our university. I admit since beginning the program a year ago, strides have been made but I think we have a lot of room for improvement.

One of our professors has improved this communication gap by creating a class blog which helps unite some of his more seasoned classes. This is a great start for those specific groups but why not get them while they are young? In this case, unless you know the professor directly you might be quite unaware that the blog exists or that your comments are welcome there. If you are not in his class or if you are just beginning your design curriculum, you may never know the opportunity that is at your fingertips.

I think it should be a requirement for students to research one another and be aware of what other design classes are doing. Now hear me out before you say that this is too extreme... let me preface with a few questions to ponder... If a past class was given the same project how did it grow from professor to professor? How did the project change with the inception of new technologies or updated program versions? How is the dynamic of the teaching style changing to provide different outcomes within the project as the professor gets more comfortable teaching or understanding the changing student dynamic? What is the teacher learning from his/her students each year that transcends into another level for next time?

Why shouldn't we be required to attend other classes to sit in on critiques and be able to give feedback on past failures vs. just allowing one single set of 20+ students decide the design fate of a semester's worth of work? To me this seems like a closing door. You may always be with those students and you never hear the possible "different" comments that can be brought up by new faces that sit in on a critique.

I am not saying that we must be everywhere at once but I do think it is important to keep others in the loop. The idea of cataloging past student's work is quite obvious but yet rarely done. Once a design is displayed for a few weeks on a wall, it is simply forgotten and the owner walks away with a rolled up poster to be lost to the current student populations' memory and nothing ahead of that.

I think it is important to maintain an open design community that engages people of all levels and graphic bailiwicks to grow. By cataloging the community through the open lines of communication; web sites, blogs and human interaction, we will ultimately provide a better seasoned designers that are not only aware of themselves but they are quite knowledgeable of the world in and around themselves.

11.25.07

04:36

Alexander Vaughn, I'm a student too and I agree that "it's just one foot at a time and try to make the best of yourself and your surroundings."

Cheers,

11.25.07

09:29

As part of the newly formed AIGA Toledo Chapter, one of the challenges we face is defying the myth of our corporate businesses who look to larger, more prolific cities to get their quality design work done. Big city now equals better work. Certainly before the proliferation of the internet, Toledo based Owens Corning, Owens Illinois and Dana corporations had most of their work done right here. With this article, it seems it is time for our chapter/designers to rediscover our history and remind these businesses of the shoulders they once stood on.

11.26.07

08:51

I WOULD GO EVERY MONTH!

11.27.07

07:38

11.29.07

12:11

There is also a VERY interesting and taboo subtext in this essay dealing with fame and ego. Why do we know the designers we know? I think it's an American value to equate success with fame and recognition and this also muddies the water of history. Design giants usually have equally giant egos and to not be known or written into history would never do for them. Modest hard working individuals often get over looked regardless of their talent level and contributions (especially great educators!) because this high level of recognition isn't a motivation for them.

Thanks Andrew, I am excited to see where this goes.

12.09.07

09:58

12.09.07

11:32