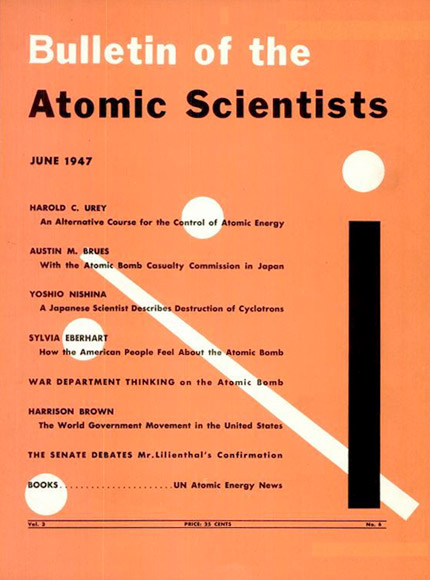

Martyl, cover of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists featuring the first Doomsday Clock, 1947.

In 1943, nuclear physicist Alexander Langsdorf Jr. was summoned to Chicago to work on a something secret, a nationwide effort called the Manhattan Project, becoming one of the thousands of scientists who would be consumed day and night for two years by the race to create an atomic bomb. They were a success: their scientific work made possible the bombs that were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, ending World War II. But, like many of his fellow scientists, he found that with that success came profound ambivalence. What were the social and political implications of this powerful new weapon? How would its use be controlled? And what did it mean that the human race had invented the means to render itself extinct?

To gain a wider audience for their ideas, Langsdorf joined other concerned colleagues in publishing a new magazine, The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

Langsdorf's wife Martyl was not a scientist. She was a successful landscape painter, known in the gallery world by her first name. Her fame was even greater within her husband's circle. As she once said, "I was the only artist these scientists ever knew." So it was inevitable that when the Bulletin's founder, Hyman Goldsmith, needed a cover design for the magazine, he turned to Martyl. It was a low budget job, two colors, a lot of type. There wasn't much extra room, but Martyl wanted to include an image that would somehow suggest the urgency of their cause. She did a number of sketches and finally hit on something she thought would work. And it did work. In fact, it might be considered the most powerful piece of information design of the 20th century. It became known as the Doomsday Clock.

For more than fifty years, arguments against nuclear proliferation have been contentious and complicated. The Doomsday Clock translates all the arguments to a simple — a brutally simple — visual analogy. The Clock suggests imminent apocalypse by marrying the looming approach of midnight and the tense countdown of a ticking time bomb. Appropriately for an organization led by scientists, the Clock sidesteps the overwrought drama of the mushroom cloud in favor of the cool mechanics of an instrument of measurement. The Clock was Martyl's idea, but she admitted she had help from a friend, Egbert Jacobson, design director of Container Corporation of America. Jacobsen suggested that the clock appear in the same design but a different color background on every issue.

There was one last crucial suggestion. Martyl had set the minute hand at seven to midnight on that first cover "simply because it looked good." Two years later, the Soviet Union tested their own nuclear device and the arms race was officially launched. "We do not advise Americans that doomsday is near and that they can expect atomic bombs to start landing on their heads a month or a year from now," wrote the Bulletin's editors. "But we think they have reason to be deeply alarmed and to be prepared for grave decisions." To emphasize the seriousness of the moment, the Clock was moved forward to three minutes to midnight. The static graphic emblem was thus transformed into a sort of political performance art, and the clock has been moved 18 times since, each time signifying an intensification or moderation of nuclear tensions.

With each change, Martyl's Clock became more deeply entrenched in the public imagination. The Doomsday Clock has been referenced in songs by Iron Maiden, The Who, and Bright Eyes. As a theme it dominates Alan Moore's graphic novel Watchmen and Senator Tom Harkin's treatise Five Minutes to Midnight. Over the years, the non-specific simplicity of the symbol was able to accommodate the new threats of climate change and bioterrorism. Finally, in 2007 (with — full disclosure — some advice from Armin Vit and me) the Bulletin's publishers adopted the clock as their organization's official identity.

The power of the Doomsday Clock was demonstrated again today. Citing "a more hopeful state of world affairs," the Bulletin's Science and Security Board moved the Clock's hand back by one minute as the world watched live online. "For the first time since atomic bombs were dropped in 1945, leaders of nuclear weapons states are cooperating to vastly reduce their arsenals and secure all nuclear bomb-making material," said the Board. "And for the first time ever, industrialized and developing countries alike are pledging to limit climate-changing gas emissions that could render our planet nearly uninhabitable." There is cause for cautious relief, but the threat remains, and Martyl's Doomsday Clock continues to tick. It is now six minutes to midnight.

Comments [16]

When the Clock's minute hand last moved in 2007, the Sun-Times published a great little story about the Bulletin's "Clock Lady." You can read it here:

http://www.suntimes.com/entertainment/galleries/215450,CST-FTR-clock18.article

01.14.10

11:51

01.14.10

12:30

It is interesting that Martyl's piece is just one of those treasured links between the past and now. I see that even in the design, with the colors selected and the clean look to the cover, that we have, today started to create designs that are familiar to the ones that Martyl created.

01.14.10

12:47

with reference and reverence and questions to Jesus' feats:

Our true home is in the present moment to live in the present moment is a miracle. The miracle is not to walk on water. The miracle is to walk on the green earth in the present moment, to appreciate the peace and beauty available now.

01.14.10

12:55

Citing the Doomsday Clock, I vividly recall (though it could have been a nightmare, I still can’t remember which) the news anchor, Jack Lescoulie, for the 1958 Today Show with Dave Garroway, saying that all predictions indicate that Russia and the United States would be involved in a nuclear war by 1960.

I’m sure you can imagine how frightening that would be for an eight-year old (or, I suppose for an 80 year old). I was always conscious of doomsday on the horizon. I receive the online Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists every month, and it still gives me the chills seeing those words as the email header.

So thanks for letting us know that “The Bulletin's Science and Security Board moved the Clock's hand back by one minute. . .” Every second counts.

01.14.10

02:09

Moving the clock's hand back by one minute shows that at least someone is optimistic. Who knew something as simple as a clock could be such a powerful icon.

01.14.10

02:58

* Not actual file name.

01.14.10

03:46

01.14.10

03:47

01.14.10

06:43

It is also a reminder that we don't control where our design can end up. I'm guessing, but I feel confident that Martyl didn't envision how widely her cover for a scientists' bulletin would spread. Fortunately she didn't treat it as a "crappy little job" and came up with a fully resolved answer.

However, isn't it really set at 8 minutes to midnight...

01.14.10

07:51

Thank you for this post.

01.15.10

08:54

01.15.10

09:23

01.15.10

10:46

It's also a potent reminder of how close we as a species have come to the brink of destruction—let's hope it keeps turning back.

01.18.10

04:51

"...their scientific work made possible the bombs that were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, ending World War II."

It should be noted that there is much evidence that WWII may have ended soon anyway (a naval blockade would likely have starved Japan into submission, for example.) The implication in the statement above is that the bombs were needed to end the war. This makes us as Americans feel a little better - that maybe this mass act of brutality had a 'positive' outcome in the long run by saving lives from a protracted war, but this is far from historical fact.

08.19.10

10:00

I believe that it is very important that these scientists who were actually the ones who helped create atomic bombs took responsibility and helped the cause reach out to a more public audience. Even though they had a part in making this disastrous weapon, they did what they could to stop the violence and get the country on board with them.

The symbol of the doomsday clock is something that I believe can be effective until we really do "render ourselves extinct". Not many images in history have had the ability to be as effective as years go by as this one and a lot can be said about the meaning and the intelligence of the design from that. The moving of the minute hand back and forth really makes us realize what this world is going through. This could make an impact on someone that could care less about how inhabitable our planet is because it is such a strong symbol.

10.13.10

04:37