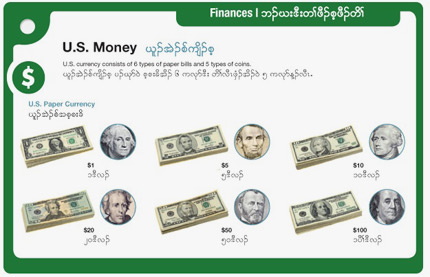

Card explaining U.S. currency from First Step's ring-bound activity book

Even in Chicago, a city chock-full of immigrants, Karen people from the mountains of Myanmar can stand out in a crowd. Shortly after Aaron Sangha and Jenn Bricker first encountered a group of Karen refugees looking for help at an Episcopal church where they volunteer, they became immersed in the day-to-day wonders (as in snow) and frustrations (as in understanding the value of a quarter) of the resettlement process. In attempting to communicate the complexities of American life to the newcomers, they developed a real-life game of Pictionary.

Sangha, a student of intercultural studies, and Bricker, a former ESL instructor, teamed up with Joyce Epolito and Rick Franklin, designers and fellow church volunteers, to launch Chicago Welcomes You, a venture to develop a kit of bilingual orientation materials. Supported by a $25,000 Sappi: Ideas That Matter Grant that was awarded to Franklin in 2008, and aided by an all-volunteer group that would eventually include illustrators, writers, translators, native Burmese consultants, resettlement experts and anthropological researchers, the quartet developed, designed and produced First Steps: An Introduction to Life in America. The kit includes a 94-page book, a set of 29 ring-bound activity cards and an illustrated storybook. Though the kit was released only a few months ago, “A wide variety of groups have ordered the materials, including school districts, resettlement agencies, church ministries and individual volunteers,” reports Heidi Moll Schoedel, national director of Exodus World Service, a resettlement agency based in Bloomingdale, Illinois, that assisted in developing and distributing the materials.

Spread from First Steps book describing medical routines

As a result of civil war and persecution dating back half a century, thousands of Karen refugees from Myanmar (formerly Burma) and Thailand have lived since the 1980s in bamboo huts in crudely managed tropical mountain camps on the border between the two countries. A loosely consolidated group of so-called hill tribes, including the Sgaw, Pho Pgho, Padaung and other minorities, the Karen have unsuccessfully tried to establish a homeland independent of the Burmese majority. Before the United Nations Refugee Agency pegged them as candidates for permanent resettlement in 2006, the Karen had no roots in America, and U.S. agencies charged with assisting them have been slow to adjust procedures to effectively manage what the State Department describes as “the most complex refugee situation.” Last year, Karen refugees constituted the biggest national group resettled in America, and as many as 55,000 Karen will have arrived in cities throughout the U.S by the end of 2009. Schoedel estimates that between 750 and 1,000 are in the Chicago area already.

Refugees enter via the U.S. State Department’s Bureau of Population, Refugees and Migration. They are immediately handed off to one of a small group of voluntary non-governmental, typically faith-based organizations, such as World Relief (a Christian not-for-profit) or the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society. Over 200 local resettlement sites, such as Exodus World Service, and various branches of Catholic Charities and Lutheran Social Services, pick up the rest of the refugees with the help of grants from the Department of Health and Human Services Office of Refugee Resettlement. The U.S. government offers a stipend of merely $850 to each refugee, and a grant of about $2,000 to the sponsoring resettlement agency. The agency must partially match this grant, and private donors and volunteers provide all other needs, including clothing, housing, English lessons and job training. The expectation is that the refugees, who are eligible to work as soon as their social security numbers are processed, can be fully self-sufficient within six months of arrival. After a year, they are awarded Permanent Resident Alien Status.

The problem is that a process that was designed for, say, German Jews fleeing to America during World War II or political prisoners escaping Castro’s Cuba is now expected to work for immigrants who may never have seen a streetlight, cooked on a stove, used a toilet that isn’t a hole in the ground or handled any type of currency. Booklets and handouts provided by governmental agencies are too simplistic to be illuminating. And the Karen are more likely than previous refugee groups to be illiterate in their own myriad and distinct languages. Few translators are available.

The designers and educators in the Chicago Welcomes You group were naturally drawn to the problem-solving aspects of Karen resettlement. “We were hard-wired to respond to this stuff,” recalls Epolito, who teaches design at Loyola University. They knew that the materials needed to be engaging and highly pictorial. Large photographs and artwork dominate the page layouts, and care has been taken to use Karen models. The Sgaw Karen text is set in KNU, an elegantly loopy font developed by Drum Publications in Thailand. The book and activity cards are broadly organized into chapters covering health, safety, housing and so on, and are designed for both organized and ad-hoc learning experiences with volunteers. A storybook, “Ah Mu Weaves a Story,” covers much of the same territory in an accessible and culturally specific format.

First Steps kit: 94-page information guide, activity cards and illustrated storybook

The elegantly printed materials are a rare example of a Sappi grant’s resulting in a product, rather than marketing, fundraising or awareness collateral. Unfortunately, however, the grant raised the bar to perhaps unsustainable levels of quality. The subsidy allows each kit to be available for only $20, and more than half of the initial run of 1,000 is already in circulation. Once the current supply runs out, the future of reprints and other translations is uncertain.

Motivated by the resettlement community’s enthusiastic reception, the group is considering founding a non-profit publishing house dedicated to refugee materials, and using students in the development process. Future iterations could be adapted for Bhutanese refugees currently flowing in from Nepali camps, and for refugees from Somalia, Burundi and Iraq. Says Schoedel, “Our goal is to find a way to get this information into the hands of anyone that needs it, either through additional language translations or through a limited English, highly visual format that could be used effectively by multiple different language groups.” With more than 100,000 refugees projected to enter the U.S. in 2010, the First Steps kit should serve as a model for upgrading our welcome.

Comments [6]

But don’t worry: By their third generation, Karen refugees will have surely lost their ancestral languages and will have converted wholesale to the upstanding, stolid American alphabet. Loops are the sort of thing a dominant majority language lobs off.

12.05.09

02:00

As a Chicagoan living abroad for some time, it's nice to know there's something like this making my home town a little more welcoming and manageable to newcomers.

12.07.09

05:18

To me, this is by far the most interesting aspect of this project. How can graphic design transcend reading and writing? what role do graphic designers play in communicating to the illiterate? Icons? Pictures? Symbols? Colours?

I don't know what the statistics on illiteracy in America are, but I suppose I can safely assume that this is not a common situation for graphic designers to find themselves in. In India, where the literacy rate is lower, there have been some, though not consistent, efforts to find answers to this conundrum.

As far as the illiterate are concerned, I don't know how successful this project will be. Especially if translators are in short supply. It seems to rely heavily on language: the pages seem pretty text heavy. Even the currency card relies on the Burmese text to explain what the notes are. How is a person who can't read supposed to decipher this? The material may be "highly pictorial", but how informative are these pictures? Can they replace the text, or at least provide a reasonable percentage of the same information?

12.09.09

10:09

http://design-altruism-project.org/?p=98#more-98

12.09.09

11:28

i'm a photojournalist and I spent several years with the karen community in karen state and Thailand. I would be interested to know more about karen communities in the Chicago area. Can you help me ?

you can find informations about my work on my website: www.lorenzodegregorio.com

thanks and I hope to hear from you

Lorenzo

12.20.09

10:42

01.03.10

07:37