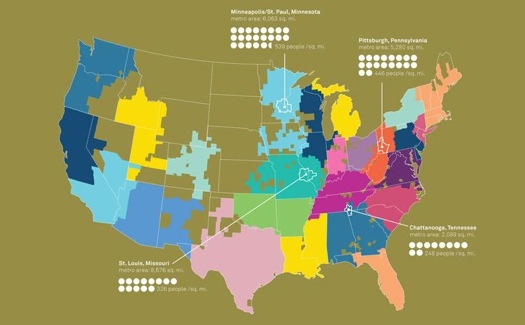

Map of communities (color patches) defined by AT&T cell phone connections, presented at "Intelligent Cities."

The National Building Museum, Time magazine and the Rockefeller Foundation have teamed up to look at urban design in a new way. “Intelligent Cities” explores how information and the new devices that communicate it can improve the places where we live. The multi-year program includes a symposium, book and Time-hosted website. The public is invited to contribute ideas via polls and online suggestions. Some of the results will be offered up in a publication this fall.

A few weeks ago, I spent the day watching a webcast of the symposium and it set me to thinking about cities and information. Some 350 people gathered in the Building Museum’s lofty hall in Washington, D.C.; about 1300 others were online. You can visit the site here.

The speaker list offered a mix of experts, planners and designers from government, nonprofits, business and academia. There were two former mayors, including Maurice Cox of Charlottesville, Virginia, and Martin J. Chávez, of Albuquerque, and a representative of the White House: Xavier de Souza Briggs, associate director for general government programs at the Office of Management and Budget.

There was a good mix of utopianism (the suggestion that there should be a “social effectiveness” equivalent to LEED ratings for architecture) and practicality. An example of the latter was a wise and weary reminder from landscape architect Laura Solano of Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates that in government, it’s tough to obtain funds for maintenance; funding new facilities, with their politically attractive ribbon-cutting occasions, is easier.Some takeaways:

What is critical in making cities “smart” is not just data, it seems, but clear, accessible data that is often used for purposes government may never have dreamed of. Early in the symposium, Judith Rodin, president of the Rockefeller Foundation, said that information to make cities smart was about “making it easier to do the right thing.”

Some data need to be taken with the proverbial grain of salt. In his new book Makeshift Metropolis, Witold Rybczinski points out the illusions that are projected by raw density stats. The standard geographical definitions of urban borders and densities often hide more truths than they reveal. Many times, suburbia is tossed into the urban core. On paper, the density of LA and Chicago look similar; in fact, their greater metropolitan areas are a mix of compact sections and loose towns.

At other times, a single number can make the point of a whole chart or map: the average Atlantan, it was pointed out, burns 762 gallons of gasoline annually.

Several speakers warned against a new digital divide. The key to making data sensible as well as smart is to make it democratic: the ideal system for encouraging citizen participation would involve mobile phones, not the web, since some 50 percent of the planet has access to mobiles, but only 17 percent to the internet.

Simply sharing data, among agencies and with the public, can help. Coordinating, say, traffic flow data and school schedules can reduce conflicts for kids walking home from third grade. In London, private users have developed smart street and subway maps.

Once-utopian ideas are now feasible, such as notions dreamed up at the MIT Smart Cities program, formerly headed by the late William Mitchell, author of City of Bits. “Smart parking places” that are RF-tagged could cut the energy wasted by circling vehicles. And systems that allow for hailing taxis and jitneys by mobile phone can provide “infill” transportation between private car and mass transit.

IBM has been working on smart traffic systems for years. The company recently implemented a congestion pricing system in Stockholm, said Mark Cleverley, the company’s director of strategy for global government Industry.

Intelligent cities can also be defined as those that use information to guide policymaking — and politics.

A few days after the D.C. conference, I stopped by NYU’s Global Design symposium, “Elsewhere Envisioned,” which touched on similar themes. Sarah Williams, of the Spatial Information Design Lab at Columbia’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation, explained a justly celebrated project of the lab that traces the costs of incarceration in poor minority neighborhoods, demonstrating that taxpayers in some cases pay $1 million a year to imprison inmates from a single Brooklyn block. That should come as no surprise, in the abstract, but is striking in the specific. SIDL’s work is a kind of antiphonal response to a very different early example of “smartening” the city: CrimeStat. In 1997, Jack Maple, a deputy under former New York police commissioner William Bratton, developed the use of basic personal computers and crime statistics to deploy police resources more effectively, helping cut crime rates.

Both cases echoed the discussion in Washington of how data can direct smarter priority choices: a homeless person may absorb $60,000 in emergency and police services, which ought to be measured against the potential cost of providing housing, the argument goes.

A more dramatic effort from SIDL involved gathering data on air pollution in Beijing during the 2008 Olympics. Reporters attached sensors for pollution levels to mobile phones. The resulting pollution maps embarrassed the Chinese government into cutting back on industry and traffic, at least during the games.

Data can also lead to more practical, political forms of intelligence. New York’s Bloomberg Administration looked at the sources of the city’s air pollution and found that removing a single component, heavy heating oil, would reduce particulate and carbon monoxide levels to an extent estimated to represent 3000 lost lives each year. The effect was about the same Mayor Bloomberg had hoped to accomplish through his congestion pricing scheme for automobiles, which was narrowly defeated by the New York State Legislature, and it was achieved with less controversy. In an ideal world, you do both, but speeding up the replacement of old building furnaces that burn heavy oil was, in the policy world, low hanging fruit.

At the same time, there is concern about data that can make cities smart: fear of information used to justify policies imposed in a top-down way, and fear of loss of privacy.

Many local communities in the past had reason to be wary of planners equipped with statistics. In the 1960s, sociologists with mainframe computers, IBM cards and Pruitt-Igoe-size slabs of data descended on cities, imposing their plans with disregard for community concerns.

The data has to be made accessible so that the public can draw its own conclusions and develop its own initiatives. Time reported on a project of the Greater London Authority to develop a website that furnishes citizens with data about itself and other public-sector organizations. Understanding that a great deal of the information is not in a user-friendly format, the project has invited technicians to transform the data into apps, websites and mobile products that “people can actually find useful.”

I learned that the city where I spent many of my growing-up years, Raleigh, North Carolina, is now jokingly called Sprawleigh. A report from CEOs for Cities lists Raleigh as one of the worst commuting cities in America, part of a group of metropolises whose residents average as much as 240 hours per year in traffic because of commuting distance. “From 1950 to 2000, “ the report said, “Raleigh's land use grew 1670 percent, 3.5 times faster than the population.” In a 2002 sprawl survey by Smart Growth America, Raleigh was ranked the country’s third worst example.

This factoid was not surprising to me: developers ran the city council in the 1960s and 1970s and set the growth pattern out into exurbia. What was surprising was that the city now has an official planner, Mitch Silver, and he is one of the best in the country. That, you might say, is an intelligent use of intelligence, in all its senses.

Comments [1]

The triple bottom line approach acknowledges that the environment os not the only challenge that communities face!

07.08.11

12:14