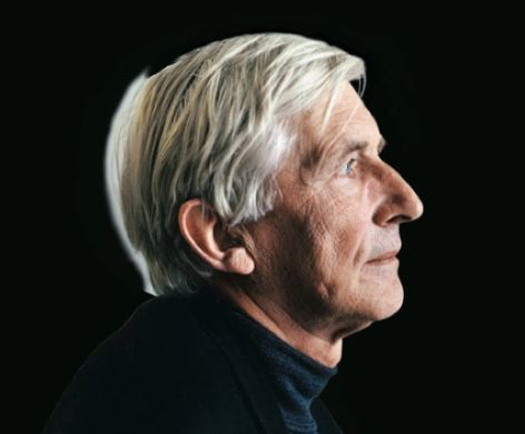

Portrait of the artist

Described by the publisher Phaidon Press as “the most famous book author you have never heard of,” Tomi Ungerer is a continental treasure in his native Europe, an artist whose life and work embody the epic forces of the late 20th century. Born in 1931 in Alsace, a region that soon became dominated by wartime Germany, Ungerer was raised under Nazi rule. His young adulthood was a mirror of postwar liberation, as he took to wandering the world before immersing himself in the invigorating climate of 1950s and 1960s New York. It was there that Ungerer made his reputation as an editorial and advertising illustrator and children’s book author, and where he became caught in the tumult of the antiwar and civil rights movements. In the early 1970s, seized by a back-to-the-land impulse, he left the States to farm in Nova Scotia. Five years later, he relocated again, this time to Ireland, where he has lived ever since.

An indefatigable proponent of progressive causes, Ungerer was made an officer of the French Legion of Honor in 2000 for his efforts to improve Franco-German relations through culture. In 2003, he was named Ambassador for Childhood and Education by the European Council and drafted the Declaration of Children’s Rights. In 2007, the government-funded Tomi Ungerer Museum opened in Strasbourg with a permanent collection of 8,000 drawings and a rotating exhibition program.

This interview was conducted in Phaidon’s New York office on June 9 during one of Ungerer’s rare visits to the U.S. He was here to promote the reissue of his Nova Scotia memoir Far Out Isn’t Far Enough: Life in the Back of Beyond, and to attend the opening of “Tomi Ungerer, Chronicler of the Absurd,” an exhibition on view at the Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art in Amherst, Massachusetts, through October 9.

Julie Lasky: You have successfully worked in advertising, political protest graphics, children’s books, filmmaking and erotica. Is it possible to do all of that anymore in a career?

Tomi Ungerer: It’s easy to preserve a style that’s recognizable by everyone, but more difficult now to range out in so many directions. I’ve also worked in architecture: I designed a kindergarten in Germany in the shape of cat; children enter through the mouth. Recently, I designed an invention for a French energy company: a double raft that is anchored on the river. Between the two rafts is a wheel that turns and takes in current. The energy that it produces lights it and animates the erotic frogs on either side of the wheel. The company had a pavilion at the world’s fair in Shanghai. I think it was the only funny element that went there.

Lasky: Even by the standards of Renaissance artists, you seem to accomplish a lot.

Ungerer: I didn’t go to college. I was not branded. I didn’t have to get rid of what I was taught; I taught myself everything. One of the most important things for one’s own development is curiosity. Once you have curiosity, you just accumulate. My interests go from botany to mineralogy, geology, anatomy, history. Sometimes I’ve been bitten like bug. I buy one object and I’m so fascinated that I start collecting. And then when I finish collecting, and the collection doesn’t inspire, I give it away, like my toy collection of 6,000 pieces that I donated to my hometown museum for children.

Lasky: When were you last in New York?

Ungerer: I have a terrible problem with chronology. I never sign my drawings or put a date on them. Two or three years ago I went through all of my drawings and signed them. That’s why they all have the same signature. As I go back through my papers and diary, it’s as If I was getting lost in time. A lot of my writing is about time. Right now, I’m writing an autobiography about my New York years. [Pause] It must have been about 15 years ago.

Lasky: You made your literary reputation in the States in the 1950s and ’60s. Why did you leave in 1971?

Ungerer: I was heavily involved against segregation and the war in Vietnam. When the war stopped, it seemed like the spirit of the ’60s ended with it, leaving a kind of a vacuum. I’d been 15 years in New York City, and suddenly I had enough. I just left.

Lasky: You went to rural Nova Scotia, a very different place.

Ungerer: Brutally different.

Lasky: Did you come back even after your erotica made you something of a scandal in this country?

Ungerer: I returned regularly. There came a point when all of my books, including my children’s books, were banished from libraries, which makes them a joy for collectors. (This happened to a whole list of authors, not just me specially.) But that was after I had already gone to Canada. I never bothered to find out how long it lasted. People look on the internet for my first American editions with the library stamp that says “Discarded.”

Lasky: Why did you leave Canada for Ireland in 1976?

Ungerer: My wife, Yvonne, and I decided to have children, but if you read my book about farming in Nova Scotia, you’ll quickly discover why it was not a place to start a family. I always say, give destiny a destination: Keep your eyes open; find opportunities. More and more, people in modern times put intelligence and knowledge over instinct. I think in life one should have a balance between instinct and logic. We were in Canada, and for some reason, all of a sudden, everyone was talking about Ireland. We went there; we liked it. Yvonne was eight months pregnant. We came to Ireland with six suitcases and started from scratch. So that’s how it worked.

When I moved to back to Europe, I engaged myself in supporting Franco-German friendship. And that’s a miracle when you think about it — a rapprochement between two nations that for centuries have been at each other’s throats. My grandmother changed nationalities five times between French and German. So many people fight for a cause and never see the end of it, are never rewarded. But it seems the causes I have picked up have been realized and I’ve been honored for it.

Lasky: Has the European Union contributed to a better relationship between France and Germany?

Ungerer: I think it’s the other way around: You can’t have Europe without a bridge between France and Germany. The Rhine is the spine of Europe. Now with the new EU countries, there are two spines with the Danube. The European Union was made possible by the rapprochement Franco-Allemagne, thanks to de Gaulle and Adenauer. Politically, it was really pioneering.

Lasky: You’ve been an activist on issues from nuclear disarmament to animal welfare. What do you consider the most pressing concern today?

Ungerer: Teaching respect of race, religion, culture, food. It should start in kindergarten. If we want peace, a bit of harmony, it’s impossible if you don’t have respect. I’ve been fighting for the sexual revolution too. Everything is a question of morals. I’ve said I don’t know how many times: You can do anything you want as long as you don’t hurt somebody — their feelings, physically. I always thought that people should play out their imaginations; everyone’s got hang-ups, obsessions. I was very fascinated with the people who are fetishists. I wrote a book on that when I was in Hamburg: Schutzengel der Holle / The Guardian Angels of Hell.

What is normal? The normal is relative to one’s origins and religion. I was brought up with a strict Protestant background; what it is normal for a strict Puritan is not normal for another milieu.

Lasky: And now you live in a country with strict Catholic traditions.

Ungerer: I love Ireland. I say that there’s not a city I’ve loved as much as New York, and now this is absolutely confirmed. The New York spirit is dynamic; it’s wonderful to be back here. But the country where I really feel at home, a country of choice, is Ireland because it’s — being from France and Germany is like being caught between two convex mirrors.

Lasky: In other words, you know what it’s like to live in a divided country.

Ungerer: I fought a lot for Alsace to have the right to speak our language. When I was young, it was forbidden. My biggest love affair in life is books and reading. And what did my teacher say? Lose your accent before you get interested in French literature. I still have my accent. I write in three languages. On top of that, there’s Alsatian, but I have an accent in every language. When I speak French, I have a German accent. When I speak German, I have a French accent. And when I speak English, who knows? It depends on which way the wind blows.

Lasky: Don’t you find that New York has changed a great deal in 15 years?

Ungerer: But not in smiling. The people in Paris could really learn something from that. As I’ve said in several interviews, this is a Babel tower. Every person you meet comes from another place. The chambermaid in my hotel is Chinese. I don’t think she speaks English, but her smile replaces everything. You have to smile. If you don’t smile, what else would you have?

Lasky: Was it your choice to title the show at the Eric Carle Museum “Chronicler of the Absurd?”

Ungerer: I’m a great fan of the absurd; I think it’s an extension of reality. I’ve always used the absurd in my books; the more I get into it, the more I tell the little crazy details. Why does the tramp carry a foot in his bag? A tramp has to do a lot of walking, like a car [that carries a spare tire] has to do a lot of driving. The absurd pushes children to ask more questions. And it puts adults in a strange situation. Some of my details are practically beyond explanation. My recent book Amis-Amies is the story of little black boy who moves with his parents into a white neighborhood. He can’t make friends and decides to have his own friends. There’s trash around the place and he uses it to build people. A little girl says, “What are you doing?” He says, “I am making friends.” In every picture, there’s a hidden faucet. Sometimes on the sofa, in the upholstery.

If you take an elephant and put a slot in its back, it turns into a bank. Imagine a 10-cent coin with a 3-foot diameter that matches. And now take an elephant and bring it down to the pig’s size. If you want to make him look like a pig, you just have to cut off the trunk, pull off the tusks, pull out his ears and twist his tail. You can already practically apply the concept to the economy and Wall Street. One of the first illustrations I sold to Henry Wolf at Esquire — a full page in those days — was a line drawing that showed the tail and foot of an elephant. At the bottom of the foot there’s a sign that says “Elephator.”

Lasky: When you were in New York hobnobbing with the likes of Henry Wolf, did you spend time with a fellow fan of the absurd, Saul Steinberg?

Ungerer: No, but before I came to America I had total admiration for Steinberg which hasn’t changed. In my museum in Strasbourg sometimes we have guest exhibitions, and the first was an exhibition honoring Steinberg. He created intellectual drawing, in a way, where you have a minimal amount of line and put in whole opinions and concepts. A lot of my books are aphoristic; I always say I write what I draw and draw what I write. The rule is always to be concise. Steinberg was really absolutely unmatchable in this way. He brought drawing to the point where a whole philosophy is packed into it.

Lasky: I’ve always loved how his work made absurdity the product of an alien’s eye. In one of my favorite New Yorker cartoons, he showed people imprisoned in Gramercy Park — an exclusive place many would kill to have access to — begging at the locked gates to be set free. Is outsider status necessary for satire?

Ungerer: I don’t like the word cartoonist; I draw pictures. But I am a satirist, something without pity, especially to the American public. I should say the Anglo-Saxon public because I have exactly the same problems in England.

Lasky: You did a lot of work for New York advertising agencies in the 1960s. That raises an important question: Have you seen Mad Men?

Ungerer: Mad what?

Lasky: It’s a TV show about people who worked on Madison Avenue in that era and engaged in a great deal of drinking and adultery.

Ungerer: Advertising was advertising. At the same time, things have changed a lot. When I arrived in New York City, there was no TV at all. Advertising went into magazines. In those days I had huge budgets. The Moon Man, it was first published in Holiday magazine: eight pages. Can you imagine that? I would sell some of my children’s books to magazines as features. Too, people have lost their innocence. In the old days, we would have funny ideas; people would laugh. Now they’ve seen everything. I see it even in myself. I hardly watch movies anymore. Sometimes I watch an old movie that was done in the ’40s or ’50s that I used to admire and now I see all the clumsiness in the acting.

Lasky: What are you reading these days?

Ungerer: Mostly diaries and letters. I just read the letters of Bruce Chatwin. For me he’s like a little brother, though I never met the man. The letters of Philip Larkin. And a book I would recommend to anyone: Waterlog. It’s by a man who swam all the rivers and beaches of England. The way it was written is absolutely exquisite. For this trip, I took The Natural History of Shelburne County, a masterpiece of the 19th century. I recommend it highly if you love nature. It’s about the third time I’m reading it. Also I’m in the middle of The Plague by Camus. I can completely identify. I took that because it was an edition with very thin pages.

Lasky: So you don’t own a Kindle.

Ungerer: I couldn’t adopt the Kindle. I’m a bibliophile. Even when I was in America I took out a subscription to The American Funeral Director, a trade magazine for the funeral industry. All of that is in my museum. I have no place for my books anymore. I give them away.

Lasky: Your drawings often depict people welded to machines, for instance, a horse and driver both cut in half and fused to the carriage wheels. Does this reflect a particular attitude about technology? Modernity?

Ungerer: I think this love of mechanism is inborn. There have been several generations of astronomical engineers in my family, including my father. He was a marvelous artist who had more talent than I. He died when I was three and a half years old, and I always had the feeling that he left me his own talent. This explains my fascination with anatomy in pictures such as a woman who is half skeleton and half black leather going into a bus. We are mechanized by our anatomy. Even in terms of thinking, there’s an anatomy of thought. How is the thinking built up? By what element? Even in this way we are much more mechanical than we imagine we are.

Lasky: What are you working on now?

Ungerer: I’ve always felt insecure about my artwork; the moment a book is published I don’t want to look at it again. Then I met the art critic Werner Spies, former head of the Pompidou, and he persuaded me that I’m an artist. I’ve gained more self-assurance. Now I’m doing a series of big collages on Waiting for Godot, which you know is really about waiting for death. It’s literally the first time in my life that I like what I’m doing.

Comments [2]

06.29.11

02:27

06.30.11

02:43