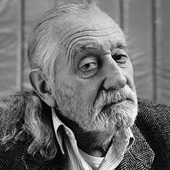

"Ettore Sottsass: Work in Progress," photo by Luca Fregoso

When I was very small, a little boy of five or six years old, I was certainly no infant prodigy, but I did do drawings with houses, with vases and flowers, with gypsy caravans, merry-to-rounds and cemeteries (perhaps because the first world war had only just ended) and then, when I was a bit older, I built beautiful, sharp-pointed sailing-boats, carved with a penknife out of the tender bark of pine-trees from Mount Bondone and together with Giorgio and Paolo Graffer we constructed cableways that were even two hundred metres long, that ran from the houses on the river Adige up to the top of Doss Trent, since we had found some balls of paper string that had been abandoned in the cellar by retreating Austrians (or maybe stolen by grandfather Graffer), and later when I was even bigger, aged eight or nine, I made barometers and wooden telescopes in my uncle Max the carpenter’s workshop to measure the passing of the stars, but naturally neither the barometer nor the telescope ever worked despite the drawings I did, of an astronomy as I imagined it and so on. It has always seemed to me the most natural thing in the world to draw and make things.

I don’t think I have ever made any great difference between drawing a thing, making it and using it or even between making things by myself or with others. If I felt like making a boat, it was I who drew it, I who built it: and I was the captain in command of it on the Pacific Ocean, defending it from mortal atolli, bringing it alongside coral beaches; when we were together, if we felt like doing a cable-way, it was we who drew it, we who made it and we the “people” that used it. And even when we did things it didn’t occur to us to deliver models to anyone, we had absolutely no conceit, no sense of power derived from the knowledge of what we were perhaps capable of doing. I didn’t feel and we did not feel like designers, or artists, or engineers for an audience and still and still less in front of an audience: we did not look either for consumers, or for observers, nor did we look for agreement or disagreement or anything that wasn’t all inside ourselves.

Everything we did was entirely absorbed in the act of doing it, in wanting to do it, and everything we did stayed ultimately inside a single extraordinary sphere of life. The design was life itself, it was the day from dawn till dusk, it was the waiting during the night, it was an awareness of the world around us, of materials and lights, distances and weights, resistance, fragilities, use and consumption, birth and death…

Now that I’m old they let me design electronic machines and other machines in iron, with flashing phosphorescent lights and sounds and no one knows whether they are cynical or ironical: now they only let me design furniture that ought to be sold, furniture they say, that is useful to society, they say, and other things that are sold “at low prices” they say, and in this way they can sell more of them, for society they say, and now I design things of this kind. Now they pay me to design them. Not much, but they pay me. Now they look for me and wait for models from me, as they say, ideas and solutions which end up heaven knows where.

Now everything seems to have changed. The things I do (by myself or with my companions) seem to have changed and the way they are done also seems to have changed because, goodbye bright blue Planet, goodbye melodious seasons, goodbye stones, dust, leaves, ponds, and dragon flies, goodbye boiling-hot days, dead dogs by the roadside, shadows in the wood like prehistoric dragons, goodbye Planet, by now I feel as if I do the things I do sitting in a bunker of damp artificial light and conditioned air, sitting at this white laminate table, sitting in this silver plastic chair, captain of a spaceship traveling at thousands of miles an hour, squashed against this seat — immobile in the sky.

By now I have to think of things from an artificial space, with neither place nor time; a space only of words, phone-calls, meetings, timetables, politics, waiting, failures. By now I’m a professional acrobat, actor and tightrope walker, for an audience that I invent, that I describe to myself, a remote audience with whom I have no contact, stifled echoes of whose talking, clapping and disapproval reach me, whose wars, catastrophes, famines, suicides, escapes, poverty or anxious restings along crowded beaches or inside smoky stadiums I read about in papers; how can I know who are the ones expecting something from me?

I would like to break this strange mechanism I’ve been driven into. I would like to break it for myself and for others, for me and with others. I would like not to have to play the role of the artist only because this way I get paid, and I wish it wouldn’t even occur to others that there’s anyone who gets paid for being an artist. I would like all of us or none of us to be artists, as we were when we did drawings, boats, ships and windmills, cableways and telescopes. I would like to think that the old happy state that I once knew could somehow be brought back: that happy state in which “design” or art — so called art — was life, in which life was art, I mean creativity, I mean it was the awareness of belonging to the Planet and to the pulsing history of the people that are with us.

I’d like to find somewhere to try out things, together, things to do with our hands or machines, in any way, not like boy scouts or even like craftsmen and not even like workers and still less like artists, but like men with arms, legs, hands, feet, hairs, sex, saliva, eyes and breath, and to do them, certainly not to possess things and to keep them for ourselves and not even to give them to others, but just feel what it’s like to do things by trying to do them, trying to find out whether everyone can do things, other things, with their hands or machines — or whatever — etcetera etcetera. Can it be tried?

My friends say it can.

Perhaps best known for designing Olivetti's iconic red plastic typewriter, Ettore Sottsass was born in Innsbruck, Austria, and grew up in Milan. An Italian architect and designer of the late 20th century, he was a leading member of the Memphis Group, which revolutionized product design in the 1980s. Ettore Sottsass died on December 31, 2007.

"When I was a Very Small Boy" ("Quando ero Piccolissimo") was written in 1973 by Ettore Sottsass and published in Terrazzo, Number 5, Fall 1990. It is published here in a shortened form with the permission of Barbara Radice and Archivio Ettore Sottsass.

Comments [21]

02.23.09

09:29

02.24.09

03:51

02.24.09

09:51

I miss drawing the way that I once did, the way that my son now does. At 5 years old his imagination is far beyond what I can reach anymore. He has no limits, no preconceptions, only what he wants to do.

Houses, cars, and of course Batman are among his favorite subjects. And I encourage him every step of the way.

02.24.09

12:36

02.24.09

01:34

Now everything seems to have changed.

Had everything changed, or had Mr. Sottsass changed? In this essay it is ambiguous what concerns him - is it a changing world, or is it growing up (and old)? Of course, this is what many of us experience. Am I the same, in a world moving beyond myself, or have I changed, exiling myself from my childhood?

It is no wonder Memphis pieces capture this grown-up yearning for play, and it is no wonder he closes his piece with an appeal to the ludic and to friends.

02.24.09

02:19

02.24.09

02:40

02.24.09

03:20

02.24.09

05:14

By complete coincidence, I did a small post on Sottsass last week on my own blog www.boym.com/blog . It must be something in the air, or maybe the feeling that he is no longer around finally settles in.

02.24.09

06:01

02.24.09

10:45

02.25.09

02:06

02.27.09

12:45

02.28.09

11:36

pretty much sums up life. money always winning.

you want to draw all the time, and you get to but now your themes are cheap furniture. from voyaging pirate ships to a coffee table.

im sorry to hear you so regretful, you should have kept it to your own liking, separated the bills from the love or made it work better.

damn i wish i could get payed to draw.

03.09.09

09:37

"Everything we did was entirely absorbed in the act of doing it, in wanting to do it, and everything we did stayed ultimately inside a single extraordinary sphere of life."

Life is about feeling every moment; about doing, being, absorbing, creating. But it seems like that is pushed aside for the sake of something "greater"; money, acknowledgement, status, etc. Unfortunately, society has made it almost inescapable to fall into a pattern of living for those things. Well, I hope along with him that we will be able to free ourselves.

03.11.09

02:21

05.13.09

11:50

We shall make it so. Oh, and break away, break away.

12.25.09

08:09

06.19.10

06:55

07.10.10

08:37

When I am ever drawn to the 'total work of art'

08.21.10

10:36