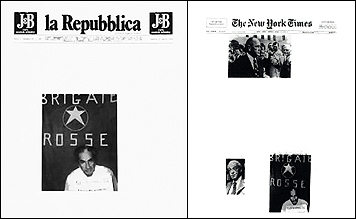

In the series Modern History (1978), the artist Sarah Charlesworth photocopied the front pages of newspapers and reframed the news by blocking out all the text, leaving only the masthead and photographs in their relative positions.

The recent controversy over whether or not to air the photographs sent to NBC News (sent posthumously by Cho Seung-Hui, the Virginia Tech gunman) reignites the moral paradox at the core of all crisis reporting. War correspondents, photojournalists and media pundits have long fretted about such decisions, which present countless questions about empathy (a subjective sentiment) and ethics (an objective obligation) and remind us that pictures, in case you were wondering, are profoundly complex.

Right or wrong (and one could argue both or either), the stills of an angry 23-year old wielding twin handguns on camera are just as disturbing as the images of bodies hurtling out of flaming windows on 9/11. (Some might argue that, because the killer himself both took and mailed the pictures to NBC, they are more disturbing.) It is perhaps fair to suggest that both events — along with their indelible imagery — have now been assured their respective places in the picture pantheon of modern-day tragedy. But does that mean they should be blasted across the front page of every newspaper all over the world?

Twenty of the world's largest news websites place the dominant homepage image in the upper left. Source: Eyetrack III, 2003.

When does a picture solidify a news story, and when does it merely sensationalize it? After seven-and-a-half hours of deliberation, argument and what we can only hope was a fair amount of soul-searching, NBC News "selectively chose certain limited passages and material to release" because, in the words of one of its more seasoned journalists, "We believe it provides some answers to the critical question, why did this man carry out these awful murders?"

Decisions about words and pictures are made by editors and publishers, designers and photographers — but they are consumed by a public fully capable of an entire range of emotional responses. Widespread misinterpretation is just as possible — indeed, as plausible — as any of the intended communications that we expect from our news media. (The growing speculation that Mr. Cho's media overexposure could so easily lead to copycat crimes testifies to this epidemic, especially if you're one of those people who thinks that there's too much crime on television anyway.) With the advent of citizen journalism, viral video and blogging, this territory grows even murkier: truth-telling, factual evidence and reality itself are not so easy to identify, let alone assess. And yet, whether by habit, instinct or sheer impatience with reading, we routinely assume that pictures speak louder than words. To this end, the labor-intensive research studies undertaken by the Poynter Institute and the Eyetrak team remind us how people look at computer screens and television screens and yes, at newspaper pages. Such studies present objectified data and thereby reinforce what many of us may have already known: bigger is usually better. Further evidence reveals that the space occupying the top left is privileged real estate.

Yet as reassuring as it may be to know this, it doesn't really go to the heart of the problem. It is hard to imagine that the repetition of Cho's likeness — a visual cue for the massive murders at his hand — would have been any less demonic had it been nudged to one side. Simply put, it's not an issue of placement so much as one of perverse saturation. And no amount of compositional ingenuity can possibly reverse that.

While testing 46 participants' eye movements across several news homepage designs, Eyetrack III researchers noticed a common pattern: the eyes most often fixated first in the upper left of the page, then hovered in that area before going left to right. Source: Eyetrack III, 2003.

In all fairness to the study, Eyetrack's disclaimer admits their research is "wide" and not "deep" — suggesting that it doesn't pretend to solve everything. Yet the news industry's preoccupation with how people digest information somehow begs the question: how does what we see — and the order in which we see it — affect us? And why should we care? Similarly, why do we need to look — if indeed we need to look at all? Perhaps because there is something about seeing the news that reminds us it's real, that it actually happened, and that there's material evidence to prove it. For multiple reasons (too much time to fill, for one) repeated exposure to the same story is the prevailing style in most 24/7 reportage. And so it goes, a tautological symphony of regurgitated images — ever expanding, never silent, feeding an incessant public appetite for tangible evidence. It's the new manifest destiny, greedy and territorial: this is truth by reiteration, not so much a reinforcement of fact as an annexation by conjecture.

Meanwhile, images — at turns cryptic and expository — engage our minds in ways both wonderful and weird. We take and make them, seek and share them, upload and publish them, distort and freeze-frame them. We are all visual communicators now: even Cho Seung-Hui chose to tell his story through pictures. (While NBC News claims its treatment was sensitive, the network also virtually cemented the killer's notoreity: as of this writing, more than twenty of the twenty-five leading news websites cited in the Eyetrack study posted either Mr. Cho's photograph or a portion of his video — or both — on their sites this week, many of them on the homepage.) Mercifully, serious and responsible journalists — and God bless them for this — remind us that veracity is a core conceit of the news: words and pictures don't tell just any story, they tell the story — the real, raw, newly-minted facts that deserve to be told. In this view, pictures of a gun-flinging madman may indeed have their place. But to the untold scores of people whose lives have been forever scarred by a senseless, incalculable human loss, these pictures are gratuitous and terrifying and mean, no matter how big, or small, or aligned to a left hand corner. And shame on all of us for needing to be reminded why.

Comments [18]

It's not new; it has been thus for as long as the news reporting business has been reporting news. Stories of Jack the Ripper in newpapers worldwide, crime photos by Weegee, the Zapruder film, Jack Ruby murdering Lee Harvey Oswald — all of these were presented unvarnished, top left.

When the news is fresh, recent and searing, we (collectively) have not been able to digest it or place it in the context of history and our own lives. This debate always crops up in the wake of a horrific event — do we report the grisly details?, is it disrepectful to the families of the victims?, can the public handle it?

It's useful to analyze what motivates these questions. Invariably, it goes to the need to protect ourselves from further pain; if I don't see the plane flying into the building again, the pain will be less sharp.

The Virginia Tech tradegy is still raw. I live in Virginia and know many current students at Tech. I have a son in college just up the road from Tech, and a daughter starting college next year. It doesn't take much for me to imagine what the parents of the victims must be feeling right now. All of our lives are forever changed by the unspeakable act of one severely disturbed young man. The question is: How do we move forward?

The redemptive power of time and truth cannot be overestimated. Knowing the full truth allows you to corral it, put a fence around the facts, face it, and know that there's nothing more. As horrible and painful as it may be, the truth is far more desirable than the alternative. In the absence of truth, the imagination rushs to fill in the empty spaces. And the imagination is almost always worse than the truth.

04.22.07

01:08

Pure-white, undulating smoke became puffy white folds of tissue. Long columns of stairs endlessly scrolled downward as long as the user dared. Ground zero transitioned from a circus, to a freak show to a petting zoo. For me I think this project gave me a little sense of control. Rather than exercise the "off" button on my remote or vow not to click on a news site, I remastered the "meaning" switch in my mind from seeing an image of terror and being paralyzed by it, to wringing out an image of terror into one which triggers a notion of comfort.

This being said, I really do think it was an exercise that can be summoned to address this latest tragedy. I, too, live in Virginia and know many many people with ties to VA Tech. I teach a student who went to high school with Cho Seung-Hui and continually work with interns as they weave in and out of the school year at Tech and other VA schools.

Rick - I think your last paragraph was very powerful and I couldn't agree more. I think that possibly, as designers, fully lucid in the language of images, we can share our insights without insciting anger or shame.

04.22.07

03:44

I am the first to admit that I am guilty of being an impatient reader at times, but this past week has made me continually dig, day after day for this so-called truth that might enlighten us of the reason(s) behind Cho's unfounded anger. Perhaps this situation hits close to home not only because I am a graduate student spending my days at a small art school campus in Providence, RI, but also because my fellow studio-mate, who sits at the desk adjacent to mine graduated from Virginia Tech only 3 years ago. Watching the continuous loop of Virginia Tech montages on CNN the day this happened, and then seeing the victims' profiles accumulate continually on various newspaper websites the days after that, I cannot help but feel that images do speak louder than words. The lush, green and beautiful Tech campus simply reminded me of my own undergraduate days at a university that so many of us called home for 4 significant years of our lives. The students at Tech are forever traumatized by a surreal tragedy that they could have never predicted. Their campus is scarred not just by an insurmountable bloodshed, but tainted by this broken trust (now reverberating around other campuses) where one cannot help but wonder: could the person sitting next to me really be capable of so much anger?

The raw quicktime movie files of Cho's manifesto spoke even louder than the stills. Although still not answering any of the pertinent questions (most important and puzzling being why he picked the victims that he did), technology has brought to life what words cannot necessarily do in exactly the same way. I was horrified, extremely disturbed, to say the least, after watching the entire movie upon clicking on what I thought would merely be stills of Cho's face. Technology has allowed anyone to document anything they want. The frontal, deadpan face of this 23-year old gunman flashed before us in episodic clips, talking directly to us as though we were in the room with him.

The only other recent time I remember feeling disturbingly uncomfortable is when I clicked on the file for Saddam Hussein's execution in December of this past year. Filmed from a cell phone, the movie clip was cryptic in a different way. I too felt like I was in the room with him, only this time as a voyeuristic spectator, instead.

We seek for visual authenticity in what we see precisely because we have become a sophisticated audience who demand for tangible visual evidence. But sometimes even these raw, unedited files cannot reveal the kind of answers that we are continually longing for.

04.22.07

06:31

The ethical reasoning for NBC's decision to release Cho's chilling images brings good points to both sides of the debate, which is completely up in the air.

04.22.07

06:44

Loren Coleman's blog has been compelling reading. He wrote The Copycat Effect about school shootings. On March 28th he wrote this:

"A deadly trend has developed in recent years. If there is a significant series of school shootings in the autumn, the copycat behavior contagion effect appears to trigger a ripple of incidents that occur in the spring. Based on such an acknowledgement of history, I have to be open about telling you, there may be terrible times ahead.

"Here is my prediction of what to expect in the next two months: There will be new school shootings with increased violent outcomes by "outsiders." Plots will be discovered, and students, especially girls and women, will be targets, victimized by adults using the vulnerable landscape of schools to work out their bloody and brutal homicidal-suicidal plans in a greater mirror of the scenarios of last fall.

"During the spring of 2007, school professionals and paraprofessionals, law enforcement officials, and mental health personnel should be aware we are entering the most active "School Shooting Season" since 9/11. From the end of March through the end of May, this window of time could be very deadly. I sincerely hope I am wrong."

http://copycateffect.blogspot.com/

Coleman's theory is that media saturation is making events like this increasingly frequent. Given that, news organisations might want to stop and consider their becoming a part-agency of events rather than mere recorders and interpreters.

04.22.07

11:19

It's sort of a funny debate to get into in the first place, but since you started it: watching people jump to their deaths is way more disturbing than Cho's photographs. His self-portraits are grandiose enough to allow us a bit of a laugh, though I agree with [I think] your overall case that Cho should be denied publicity, to the small extent that this is possible.

I have little else to say about Cho, and I say it here:

Seung Hui Cho and "Oldboy"

04.23.07

11:55

Mental health professionals are on the front lines of our changing psyche, but they are basically ignored and under-funded until something like this happens at which point everyone points their finger at the school psychologists. Can media studies, blogging or even film-making be integrated into mental health practice? Could a therapeutic use of a video-camera have helped this kid shape a narrative of alienation more along the lines of The Graduate than Old Boy?

04.23.07

04:47

Jessica asserts that the relentless and repetitive reporting is feeding an "incessant public appetite for evidence." I completely disagree. I think this reporting is feeding a voracious public appetite for entertainment. Violent entertainment in particular.

I suppose, as communicators, we should be thinking about the power of images used in the news media. But, frankly, in the face of this disaster, that question pales in comparison to the larger issues at hand. Why is our country so utterly and completely obsessed with violence? Why does violence pervade so much of our media, our news, our TV shows, our movies, our literature? To use Jessica's phrase, it is "perverse saturation." The tragic Virginia Tech massacre is just another example. It has been completely sensationalized in the media from day one. The media have portrayed this horrific real-life event (along with so many others) as though it is just another piece of entertainment. Our culture laps that it up like it is a drug--or like it is the latest horrifyingly-violent TV show or movie. I don't think we know the difference between entertainment and evidence any longer.

And if even if it really IS evidence that we need, WHY do we need this evidence? Did we really need to see Cho's video manifesto to know that he was deeply disturbed? Was it not enough to trust our media's reporting of that?

There's obviously the question of whether violence portrayed in the media incites more violence in the real world. Well, if there is even a slight chance that it does, shouldn't we be trying to rein in the violence in the media? Likewise, shouldn't NBC have had the good sense to not broadcast Cho's disturbing manifesto?

Well, like the vast majority of Americans, I am a person who was not even remotely affected by what happened at Virginia Tech. I live in Pittsburgh, not Blacksburg. I have no friends, colleagues or relatives affiliated with Virginia tech. I have no connection to it whatsoever. That is not to say that I do not feel sympathy for the victims. I certainly do. I just don't think it is any of my business to know all of the lurid details which the media is trying to shove down my throat. Again, it is not evidence, it is an increasingly sickening form of entertainment. A disgusting perversion.

In 1977 seven of my family members were killed in the Beverly Hills Supper Club fire outside of Cincinnati. There, was, of course, a huge amount of reportage. But, we didn't go on talk shows or answer intrusive media questions. Nobody needed to know more about in exactly which excrutiatingly horrible manner our relatives died. Nobody had any business knowing how we felt--as if they even could. Today, the general public seems to think they have some right to this knowledge--as though maybe they do think it is "evidence." But, again, it is really just some sick form of entertainment. Maybe, just maybe, the public's voracious consumption of tragic news delivered ad nauseum amounts ot a misplaced desire to feel empathy for the victims. Well, I can tell you that until you have directly and personally experienced one of these tragedies, you simply cannot have any idea what it is really like. The notion that the media is broadcasting this stuff out of some attempt to foster empathy is patently absurd. So, again, it is reduced to entertainment. It's a terribly distressing state of affairs.

04.23.07

05:31

Added to this, the Net and channels like CNN cater to the global audience, all of whom are interested in world events. Because of time differences (and local channels catering to the shift workers in our 24/7 working week) news items get repeated for the benefit of others and also as any updates to the news event occurs. This can also look like saturation, but it's not always intentional.

The following is one of the most horrific and harrowing images of a bygone era.

http://www.palmbeachpost.com/news/content/news/special_reports/war_photos/NY2044_AP_CENTURY_COLLECTI.html

Either way you look at it, the associated story is just as chilling. Harrowing and disturbing as this is, images and news coverage of this nature are critical to how the rest of the world views events as they happen (and after). At the time, they are a rude - but important - wake up call, stirring up crucial and much needed debate (and action). Afterwards, they live with us forever as a reminder of what should be - or could have been - prevented.

If anything, the coverage of the deeply saddening Virginia Tech Massacre has highlighted American policy on gun control and reignited that particularly important debate. And this was prompted by 'an over-saturation' of a news item. But we shouldn't only be wondering why the Virginia Tech tragedy seems to be 'another Columbine'. One was more than enough. As Rob points out, the incredible appetite global audiences seem to have for 'violence as entertainment', America in particular, is the bigger issue.

Admittedly, I don't know what the media coverage of this awful event has been like in America but I believe the real issue is not about the saturation (or quantity across the various media channels) of particular images. It is more about the sensationalism of events - for the purposes of ratings, which is sensationalism at its worst.

Unfortunately, along with other forms of information channels, there has been an increase in the number of tabloid-style news broadcasters as well. It is here, in the hands of these spin-doctors, news items always appear insensitive. The saddest thing of all is, as Rob points out, there appears to be a voracious market for this particular style of news broadcast. The question remains: are we simply looking at a frightening but real equation of supply and demand?

04.23.07

11:40

I for one am Tired of all the armchair generals. Tired of all the hindsight, and vampiric thirst for academic fodder. Tired of people getting their main source of knowledge and culture from "the online community". No one cared about this kid "falling through the cracks" before he could kill people. Tired of anyone who lies and says they did or would. And as a result, tired of the predictable commentary on media regarding the incident. In some way I find it just as annyoing as a tabloid media with no conscience to listen to a bunch of defensive, insecure artists and academics pontificate about the implications of the event. I just picture you typing, typing and typing. Clicking, clicking and clicking. Reading your own post and admiring the quickness of your own intellect and wit. I sometimes wonder what's worse, the tabloidization of our mainstream journalism or the watering down of the discourse with all this endless narcissistic posting and blogging.

Somebody's sitting somewhere wondering every single minute since it happened if they can go on living without someone they lost at VA tech. To quote Ezra Pound, "What thou lovest well remains, the rest is dross".

04.24.07

03:15

04.24.07

08:28

I think your contempt is a bit misdirected. You're tired of people getting their main source of knowledge and culture from "the online community," yet you read and comment on a well known, online public forum.

04.24.07

08:58

It is inevitable that a story of this magnitude will be covered proportionally by the media. That's a given. In an open society, while some of that coverage will be cynical and sensational, most of it will be direct and accurate, some will be exemplary. It's a classic bell curve--10/80/10-- 10% of the coverage is outstanding, 80% is average, 10% is despicable. This is a system we should not tinker with. It's a very slippery slope.

regarding the motivation for following this particular story:

I disagree that people around the world are interested in this story because of a "voracious public appetite for entertainment. Violent entertainment in particular."

A story of death caused by accident doesn't have "legs" because of the randomness of accidents. It was no one's fault; it just happened. A car skidded on a road. A tree fell on a house. Lightning started a fire. The insurance guy calls it an act of God. We can relate to the story because we have all lost someone we know and love.

The Virginia Tech story is fundamentally different. The deaths were not caused by accident; they were caused by another human being--someone who looked and acted like the rest of us. There is a deep need in all of us to understand the behavior of others who deviate from socially acceptable behavior. And when faced with an individaul like Cho who deviated so radically, the interest in the story goes far beyond a "voracious public appetite for ...violent entertainment...". I feel that it goes to a deep sense of self-preservation and self-understanding. The question of "Why did he do it?" is central. To ask that question both privately and publicly, debate it, air it for as long as need be, is required for us all to move on.

regarding censorship:

Rob wrote: "And if even if it really IS evidence that we need, WHY do we need this evidence? Did we really need to see Cho's video manifesto to know that he was deeply disturbed? Was it not enough to trust our media's reporting of that?

There's obviously the question of whether violence portrayed in the media incites more violence in the real world. Well, if there is even a slight chance that it does, shouldn't we be trying to rein in the violence in the media? Likewise, shouldn't NBC have had the good sense to not broadcast Cho's disturbing manifesto?"

I find disturbing the suggestions that there be some sort of censorship (even self-imposed) on the "evidence" gathered at Virginia Tech. That always brings up the question of who is qualified to make the decision on what we should see and what we should be "protected" from. As painful as it is to see inside the mind of a madman (...or his version thereof...), it adds to our understanding of the world around us.

regarding the search for a positive note:

I find it interesting, and upliftiing, to see how the Virginia Tech community (primarily 18-22 y.o. kids) has handled this tragedy. They came together in a healthy and supportive way, allowed the world to watch, then announced yesterday that it was time for the media to leave so they can get back to their lives. If this group of students represents our future, I'm encouraged.

04.24.07

01:50

The 165 deaths in the Beverly Hills Supper Club fire were not the result of some random accident, some capricious "act of god." They were the direct result of human negligence. Yes, those deaths absolutely were someone's fault. In that way, they are the same as the VT massacre. The key difference being, of course, that the latter was intentional, the fire unintentional. All of the same questions are raised. Why did it happen? How could it have been prevented? Who could have prevented it? And so forth.

As for censorship (which I did not mention in my post), well, how do you define censorship? Was it "censorship" when media decided not to show the video of Daniel Pearl being beheaded? Or was that just good judgement? The media can, and should, exercise good judgement--which is what I would hope for--and they can do so without that being pejoratively labelled "censorship."

04.24.07

04:22

I obliquley referred to the Beverly Hills fire you mentioned in your initial post as an accident without knowing any of the facts. I apologize for speaking without knowing. A google search reminds me of the details and enormity of the Beverly Hills fire.

04.25.07

09:04

I think putting a face on hate is to give hate power. Showing those images accomplished nothing more than the spread of another hateful image.

What if we took another approach? The Christian Science Monitor responded with a headline "In tragedy, a pulling together." The cover photo occupying that prime visual realestate was of mourners at a group vigil.

People forget that there is an entire flip side to the coin of every story, and that is just as truthful and far less harmful than images of Cho pointing a gun at our heads.

When Al Qaeda detonates an IED and blows up our men and women in uniform do we really need to see the terrorists face while pressing the cell phone button to understand that there was hate involved? Who beyond the people going after the terrorist needs to see what he looks like?

04.25.07

11:12

not to be a turd, but he did not send the photos to nbc "posthumously" — he sent them while he was still alive. you could say they arrived posthumously, but not sent...

04.25.07

01:33

The force behind much of the coverage stemmed from designers deciding how a page should look. Little of it stemmed from solid news judgment, and even that judgment was usually exercised after the visual decisions were made.

It's a serious problem that far more newsrooms should be addressing.

Many readers were unhappy with the coverage of this event, and a lot of them have good reasons.

04.28.07

05:30