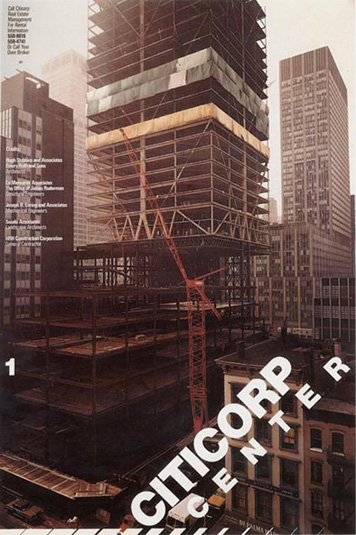

Poster for Citicorp Center, Dan Friedman for Anspach Grossman Portugal, 1975

You've taken on a design challenge and come up with a solution that's been widely admired and won you accolades. But a year or so later, you realize you made a mistake. There's something horribly wrong with your design. And it's not just something cosmetic — a badly resolved corner, some misspaced type — but a fundamental flaw that will almost certainly lead to catastrophic failure. And that failure will result not just in embarassment, or professional ruin, but death, the death of thousands of people.

You are the only person that knows that something's wrong. What would you do?

This sounds like a hypothetical question. But it's not. It's the question that structural engineer William LeMessurier faced on a lonely July weekend almost 30 years ago.

LeMessurier was the structural engineer for Citicorp Center, arguably the most important skyscraper built in Manhattan in the years of the 1970s recession. Most people who know this landmark know it for two things: its distinctive, diagonal crown, and the four towering columns centered on each of its sides that seem to levitate it above Lexington Avenue. Architect Hugh Stubbins deliberately moved the columns from the corners in order to accomodate St. Peter's Church, which had long stood on the site's northwestern edge. William Le Messurier and his engineers had to figure out how to make sure the building would stand up on this unusual base. Their solution, a series of diagonal braces and a rooftop damper to limit the structure's sway, was acclaimed for its elegance and innovation.

A year after the building's opening, LeMessurier recieved a call from a student working on a paper, asking about the unusual position of the columns. LeMessurier answered the question, but something about the conversation started him thinking. He revisited his calculations and began to realize that under certain wind conditions, the bracing might not be sufficient to stabilize the building. A series of seemingly trivial mistakes and oversights, none significant alone, had combined to create a potentially dangerous situation. His concern mounting, he consulted a fellow engineer named Alan Davenport, an authority on the effect that winds have on tall buildings. Davenport reexamined the data and confirmed his worst fears: as it was currently designed, sufficiently high winds could indeed knock down the Citicorp building. Those wind conditions, LeMessurier was told, occur once every 16 years.

The story of William LeMessurier and Citicorp Center was first told in a brilliant New Yorker article by Joe Morgenstern in 1995, "The Fifty-Nine-Story Crisis." In it, Morgenstern describes what LeMessurier faced as he realized that his greatest achievement was instead a disaster waiting to happen: "possible protracted litigation, probable bankruptcy, and professional disgrace." It was the last weekend in July. The height of hurricane season was approaching. He sat down in his summer house to try to figure out what to do. Morgenstern describes what happened next:

LeMessurier considered his options. Silence was one of them; only Davenport knew the full implications of what he had found, and he would not disclose them on his own. Suicide was another: if LeMessurier drove along the Maine Turnpike at a hundred miles an hour and steered into a bridge abutment, that would be that. But keeping silent required betting other people's lives against the odds, while suicide struck him as a coward's way out and — although he was passionate about nineteenth-century classical music — unconvincingly melodramatic. What seized him an instant later was entirely convincing, because it was so unexpected: an almost giddy sense of power. "I had information that nobody else in the world had," LeMessurier recalls. "I had power in my hands to effect extraordinary events that only I could initiate. I mean, sixteen years to failure — that was very simple, very clear-cut. I almost said, thank you, dear Lord, for making this problem so sharply defined that there's no choice to make."

LeMessurier returned to Boston and told the building's architect, his friend Hugh Stubbins, what he had discovered, that Stubbins's masterpiece was fatally flawed. As LeMessurier told Morgenstern, "he winced," but understood immediately what needed to be done. The two men went to New York and told John Reed and Walter Wriston, respectively Citicorp's executive vice-president and chairman, everything. "I have a real problem for you, sir," LeMessurier began.

Remarkably, and perhaps disarmed by the engineer's forthrightness, the bankers didn't waste time assigning blame or brooding about how to spin the situation, but simply listened to LeMessurier's ideas about how the building could be fixed, and committed themselves to do whatever it took to set things right. With Leslie Robertson, the engineer of the World Trade Center, the team devised a plan to methodically reinforce all the bracing joints a floor at a time. The repairs would take the better part of three months, with work happening around the clock. Evacuation plans were put in place; three decades ago it was unimaginable that a building would fall down in Manhattan, and no one knew how extensive the damage might be. In the midst of it all, on Labor Day weekend, a hurricane began bearing down on the northeast. It veered out to sea before the building could be tested. All of these events were largely unknown until Morgenstern's New Yorker story, because of a bit of luck for LeMessurier and Citicorp: New York's newspapers went on strike the week the repairs began.

By mid-September, the building was fully secure and the crisis had passed. In the aftermath, Citicorp agreed to hold the architect, Hugh Stubbins, harmless. And, amazingly, although there were accounts that the repairs cost more than eight million dollars (the full amount has never been disclosed), the bank opted to settle with LeMessurier for two million, the limit of his professional liability insurance. The engineer was not ruined. In fact, as Morgenstern observes, LeMessurier "emerged with his reputation not merely unscathed but enhanced." His exemplary courage and candor set the tone. As Arthur Nusbaum, the building's project manager, put it, "It started with a guy who stood up and said, 'I got a problem, I made the problem, let's fix the problem." It almost seemed that as a result everyone involved behaved admirably.

We designers call ourselves problem solvers, but we tend to be picky about what problems we choose to solve. The hardest ones are the ones of our own making. They're seldom a matter of life or death, and for maybe for that reason they're easier to evade, ignore, or leave to someone else. I face them all the time, and it's a testimony to one engineer's heroism that when I do, I often ask myself one question. It's one I recommend to everyone: what would William LeMessurier do?

Comments [45]

04.06.06

01:43

04.06.06

01:56

04.06.06

02:11

BTW, here's a link to that Düsseldorf airport fire story and Meta Design's role in the aftermath.

04.06.06

03:09

04.06.06

03:15

04.06.06

03:16

Fantastic article.

Your last paragraph is what really struck a chord with me. Truly puts into perspective about the how trivial it seems when some of us grit our teeth (or avoid altogether) when admitting to our own mistakes (in comparison to what William LeMessurier was faced with).

04.06.06

09:49

04.07.06

12:01

the point that you are making in this story is a point so pointless that it closely resembles a broken pencil. I do not understand how not to point my finger towards the pointy aftermath of the point in this story.

It is a point that has been raised in the presence of a pointless perspective which administers its heavy burden of guilt upon those whose fault it never could have been. Since the early times man has been saying; 'all your base are belong to us' and it is this perception of the evil empire that Citicorp understands, and frequently corrupts, through its media fanbase in the form of bloggers and emo-loggers that wander through the woods.

Ask not wether the point should follow the sentence, ask wether the sentence should be written at all.

04.07.06

05:08

What is your point?

That the building should not have even be built in the first place? And are you saying that Michael Bierut is one of Citicorp's wanderers of corruption?

I am not sure what you are trying to communicate, it is unclear.

04.07.06

09:20

I am hesitant, however, to applaud someone for making what I, and most people, would see right from the beginning as the proper (and only) decision. Should we applaud LeMessurier for not killing himself? No. We should simply be glad that someone with that piece of information acted as any human should. Just because someone didn't make a selfish decision doesn't make them selfless.

There are people much more worthy of the "What would ... do?" line of thought.

04.07.06

10:50

In response to Susan's comments: Are you proposing the building should have never been built?

Is that like saying a book with an editorial error or a typo should have never been printed? Or a magazine with a factual error should have never been printed? While we strive for perfection in our work and we have processes to avoid those mistakes, sometimes they happen regardless of our precautions.

We're human. It's how we deal with our shortcomings that makes us more authentic. We own up to our mistakes, admit them, correct them, apologize, ask for forgiveness... whatever is needed to rectify the situation and we move on. If we miss this aspect of humanity, we're missing something crucial in our professional and personal lives.

04.07.06

10:51

04.07.06

12:44

04.07.06

01:49

04.07.06

02:49

I am waiting for a film of this story, one starring, at the low end, Tom Hanks as LeMessurier, or, at the high end, Goeffrey Rush.

For the female interest, again at the low end, Naomi Watts, or, at the high end, perhaps a cgi Anna Magnani.

Thanks again for a FABULOUS story.

04.07.06

04:05

The John Hancock Building in Boston required rather more significant retrofitting to make it safe, after opening in 1976. Problems included a nauseating sway (solved by a "tuned mass damper"), falling 500 windows and, most pertinent to this thread, the threat of tipping in strong winds.

I'm writing from memory, aided by some additional information at answers.com.

04.07.06

04:39

i applaud lemessurier for his actions. as a student at harvard's graduate school of design in the early 90s, lemessurier cited this story in his lectures as a lesson to others -- to act honorably and honestly.

04.07.06

05:02

What has impressed me about this story from the first time I heard it was not that LeMessurier told Citicorp about his mistake, but how he did it. No excuses, no hedging, no shading the truth to minimize his role. Just the plain and simple route: admit the mistake and take full responsibility for it, and face the consequences head on.

Sam, if you think this is commonplace behavior, you live in a different world than I do.

04.07.06

11:12

04.09.06

04:24

What LeMessurier did at the end was part of his job as a structural engineer - and I'm sure that's the reason why Citicorp took it so matter of fact. Not really a choice between 3 options, just one option available if you take your chosen profession seriously.

04.09.06

05:27

But we should perhaps ask ourselves why it is that we need examples to tell us what is right.

Undoubtedly, in matters of self-preservation, the unethical decisions of humankind outweigh the ethical ones. Someone once told me that we do not live in a fair world, but in a just world. Unless one considers survival of the fittest to be the best rule of the land (given the contrary, that our will can act against our instinct), it is impossible to believe either premise in bearing witness to the multitude of infractions that surround us. There is a lack of good example.

Most people can walk away from their mistakes with a "better luck next time" attitude. No harm, no foul. This may translate however to harms done off camera, to the non-audiences, the uncounted, the inconsequential. A no vote is a vote for the victor.

However, those with the attitude that every element matters may be more likely to run with the ethic that every person matters. We will never know the consequences of the decisions LeMessurier did not make, nor can we assume that he made the right decision from a sense of duty to his fellow man. In matters of conscience all options may be equally discernable, but only one is viable. Still, by most any standards, he did the best thing for everyone involved, visible and invisible. Shouldn't we all?

P.S.

Spelling error, paragraph 7:

"I had power in my hands to affect extraordinary events that only I could initiate."

04.09.06

06:25

04.09.06

08:26

04.09.06

09:10

04.09.06

11:28

04.09.06

11:30

No excuses, no hedging, no shading the truth to minimize his role.

...

Sam, if you think this is commonplace behavior, you live in a different world than I do.

As unfortunate as it is, I certainly don't think LeMessurier's actions were commonplace. I just fail to see why he is put on a pedestal for taking the blame for something that was purely his error.

I suppose I've never much been a fan of the 'What would So-andSo do?" phrase. How about "What did my mother teach me to do?" or "What would I, at my most noble and humble, do?" when presented with a situation like this; or do we generally feel too overwhelmed when matching our own conscience with what seem to be difficult positions?

04.10.06

09:51

A sidebar: the architectural design of Citicorp was often written up as creative genius at the time, because there were no other buildings like it. But the building was originally designed for a Wall Street site, and then recycled when that building wasn't built. I don't remember if the first was designed by Stubbins or someone else like Ed Barnes.

The diagonal top was supposed to be a functional result of a decision to put solar panels on the top. But the panels were axed and the diagonal stayed.

My point? The myths of Modernism were so mythic that they often prevailed over fact.

04.10.06

10:59

I think it is because he did not pass the buck and owned up to his mistake—something that is unusual.

As I write this I am listening to a radio broadcast about the Enron trial. The former CEO has pleaded not quilty saying he didn't know about the fraud going on in within his own company. He has tried to passed the buck to underlings who supposedly knew more about the company than he did.

I don't think anyone is really surprised at this finger pointing.

04.10.06

12:09

He is to be commended because he fulfilled his responsibilities as a professional engineer and in addition he took responsibility for fixing a mistake that was not his own. An interesting side bar is that despite his insurance company eventually paying 2 million dollars they lowered his premiums.

04.10.06

09:51

04.10.06

11:03

I agree with Massengale that there is far too much myth surrounding the nobility of Modernism. The truth is that Modernism erased and removed so much of what is human from the arts, and traded it for sensationalism and self-aggrandisement.

04.11.06

08:37

"Own up to your mistakes, and things won't be that bad. In fact, you might end up better off." (no doubt Aesop could make that snappier!)

Fables need to be about situations that we can relate to. They set standards for moral behavior and relate rewards and punishments that may follow depending on the paths that we take. But it's the very ordinariness of LeMesurrier's moral dilemma that makes it a story worth recounting.

04.11.06

10:00

look fr studioLDA

04.16.06

10:50

But in hindsight 20/20, I have to ask this: seeing as he is obviously a trained professional, with an established career and reputation, how could he have POSSIBLY made such a mistake? I understand the old "everyone makes mistakes" adage, but I think that at this level, it's unimagineable that any professional could make such a mistake with potentially horrific consequences.

04.16.06

03:44

As I said in the original post, there were actually a series of miscalculations and mistakes, all of which are described in greater detail in the original New Yorker article.

One of these was something that Craig mentions in his comment above: the substitution of bolted braces for welded braces, which was done without LeMessurier's knowlege as it was standard practice in similar tall buildings. LeMessurier could have easily blamed his steel supplier and local consultant for the whole thing, since they had signed off on this substitution.

I am convinced that 99% of us in his situation would have figured out a way to pass the buck; I certainly would have seriously considered it myself, I'm ashamed to say. That LeMessurier didn't is what I really admire.

04.16.06

04:19

It is almost always harder to do the right thing, but it is still the right thing to do.

04.17.06

08:46

- Badri

04.18.06

06:12

04.24.06

01:16

dw

04.26.06

11:44

05.07.06

09:30

05.08.06

04:35

05.13.06

11:00

08.20.06

07:06

04.25.09

06:51