When I was a kid, my mother had a few cookbooks, passed down as heirlooms, on the bookshelf. Occasionally when I was feeling rather confident, I would pull one in particular down to peruse its pages. It was The Joy of Cooking. But, as I entered into a foggy haze induced by pages upon pages of small black text, I found myself overwhelmed by its contents. In retreat, I would set the book back where it belonged—on the shelf, just slightly out of reach. I did not find joy amongst its pages. In fact, what I probably thought was, “Please, don’t leave me alone with these recipes.”

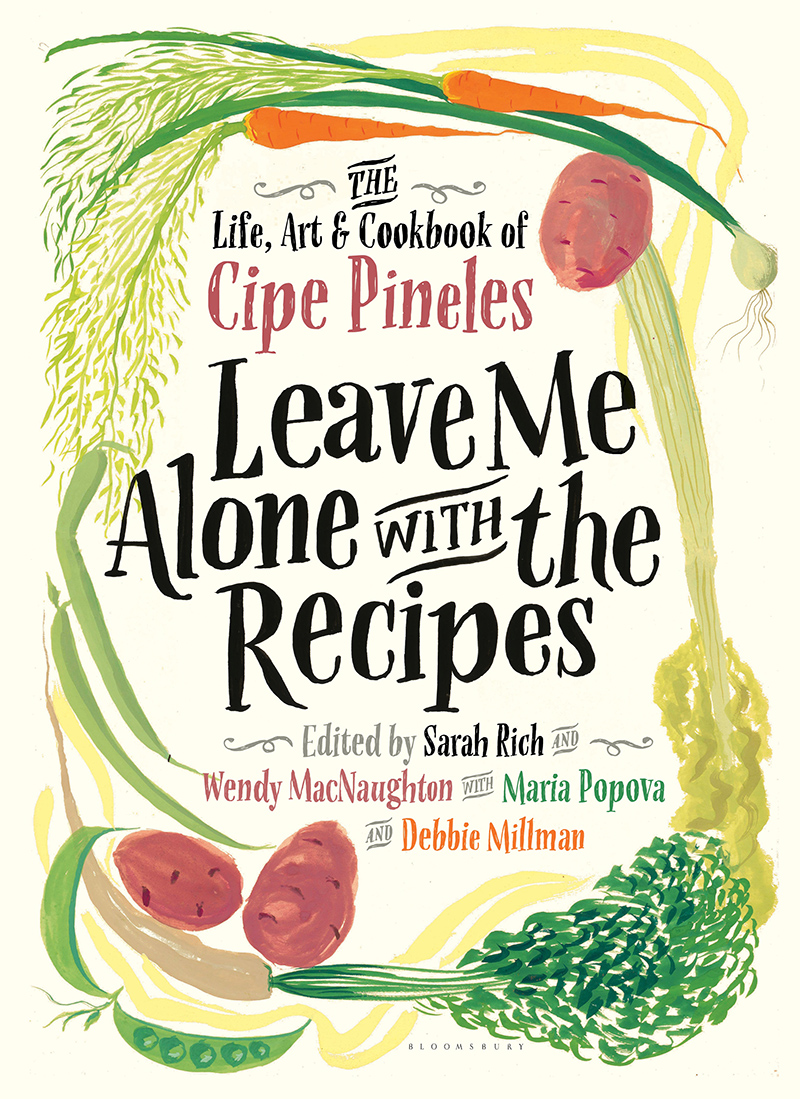

AIGA Medalist Cipe Pineles, who authored and illustrated Leave Me Alone with the Recipes, was of the same era but of a different discipline. After coming to the United States from Eastern Europe, Pineles became the designer of magazines such as Glamour, Mademoiselle, Vanity Fair, and Vogue, and the first female art director at Condé Nast. After graduating from Pratt in Brooklyn, New York, with a portfolio that according to founder of Brain Pickings Maria Popova, was “strewn with food paintings, from a loaf of bread to a chocolate cake,” Pineles secured a position at Contempora as a textile and display designer.

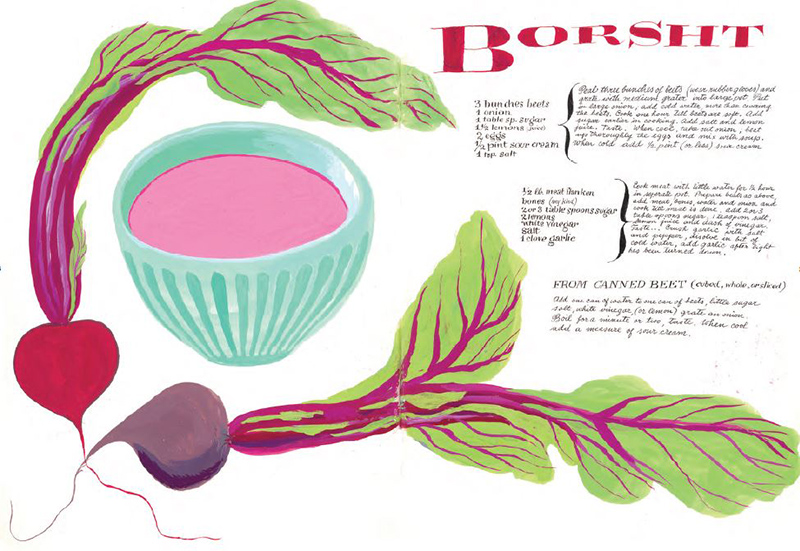

The fortuitous moment occurred when Condé Nast himself saw her pattern designs and hired her as an editorial designer for Vogue and Vanity Fair. By the mid-1940s, Pineles was heading up Glamour’s design team. It was during that time that Pineles created the illustrations for Leave me Alone with the Recipes, a collection of family recipes handwritten and illustrated by the art director herself, but they wouldn’t be discovered until decades later, when Sarah Rich and Wendy MacNaughton discovered the collection at a book fair in California.

In the 1960s, Pineles took on food from a new editorial angle by launching the magazine Food & Drink. According to Sarah Rich in her essay from the book, “Food & Drink,” it was not meant to be simply instructional but would pull food and its preparations out of the domestic sphere—analyzing issues adjacent to the subject conceptually and intellectually, with an audience of both men and women. This too contained hand-sketched pages. It was meant to surprise and to challenge. Like what Rich calls the magazine’s contemporary equivalent, Lucky Peach, Food & Drink soon dissolved. But the entwinement of food and design continued to make small imprints in Pineles’ career.

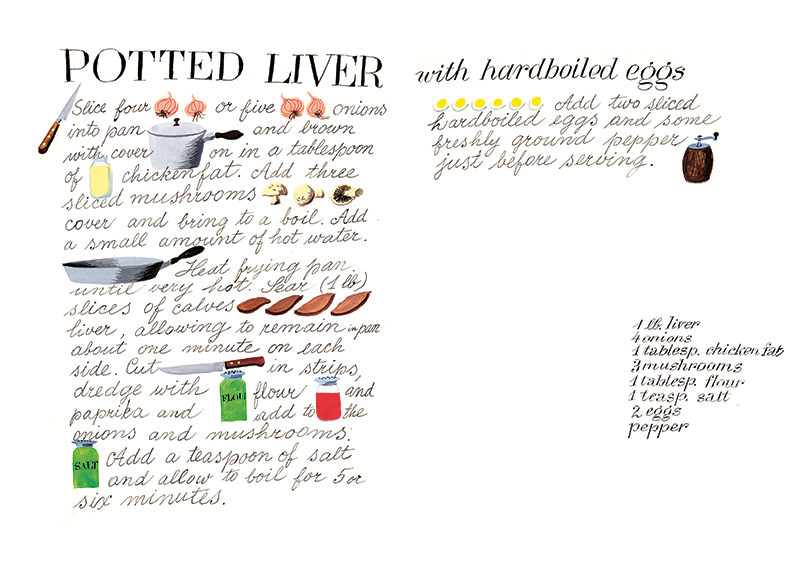

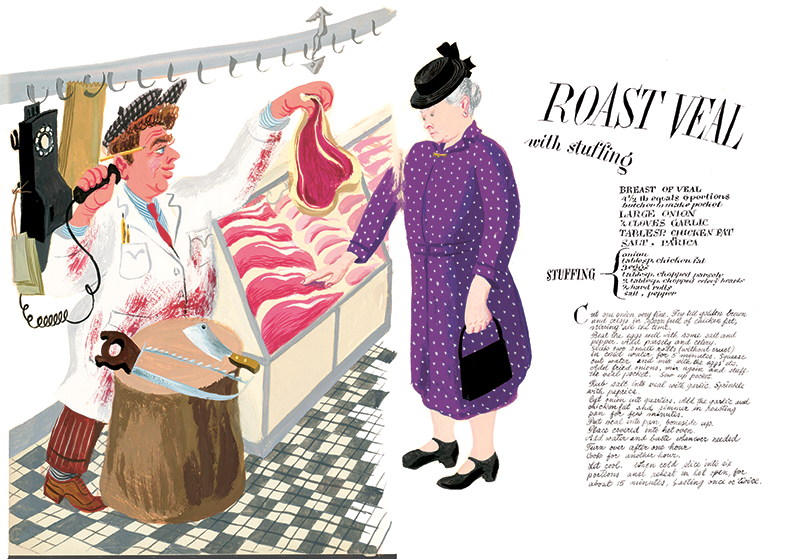

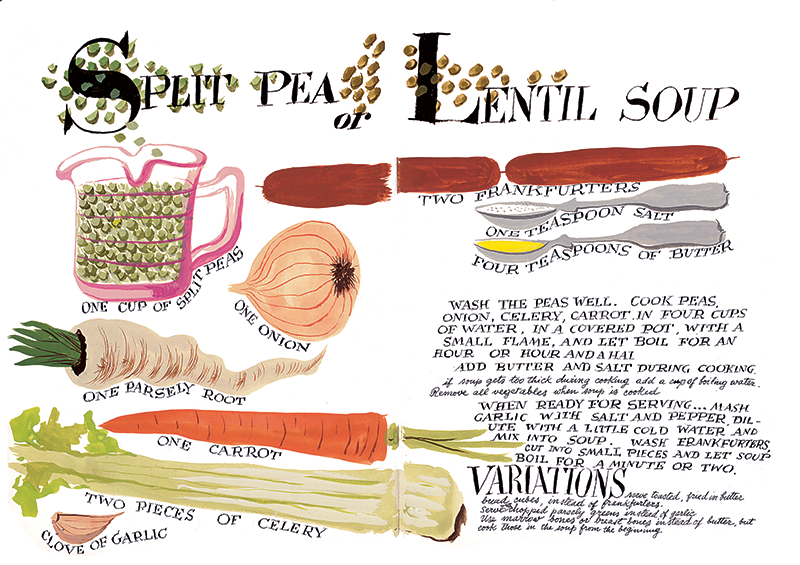

And so, likewise, Pineles’ take on home cooking, newly discovered through Leave Me Alone with the Recipes, induces a different feeling. Her illustrations create a friendly entry point and show, now that they have been rediscovered, the power design can have in impacting the everyday experience. As illustrator Wendy MacNaughton said in her contribution to the book, “In Defense of Food Illustration,” “Illustration can convey a love of food and aesthetic in a deeply personal, sensual, accessible way that other mediums cannot. It’s what Cipe Pineles did in her cookbook in the 1940s. And it’s what many people are getting back to doing now.”

As photography became less expensive to produce and reproduce, it overtook etchings, lithography, and illustration as the graphic support of choice in cookbooks. In present day, we swim in the photographic image. But the effect of the photograph, depicting a literal outcome, can leave the aspiring chef to wonder if they got the recipe right or wrong: Does it look the same? Illustration, by the nature of being done by hand, is not a prescription for how the recipe should turn out. As McNaughton says, Pineles’ “drawings, lettering, and composition are far from perfect, but everything always ends up looking just right.” Her illustrations embody a feeling of intimacy, not as a measure of clinical success.

From the early part of the nineteenth century through, some might say, a good portion of the last one, middle-upper class society was dominated by two spheres: a women’s sphere, private and domestic; and the men’s sphere, the public world of business and enterprise. Called the “Cult of Domesticity,” this was the directive under which a sophisticated society lived: that like the different spheres of living, men and women were inherently opposite and complementary. Women were pious, moral, and domestic; men were enterprising, political, and willing to get their hands dirty. Where did these ideas come from? From fiction, peers, churches—and magazines. And while these ideas might seem anachronistic, history holds ties that can be hard to break.

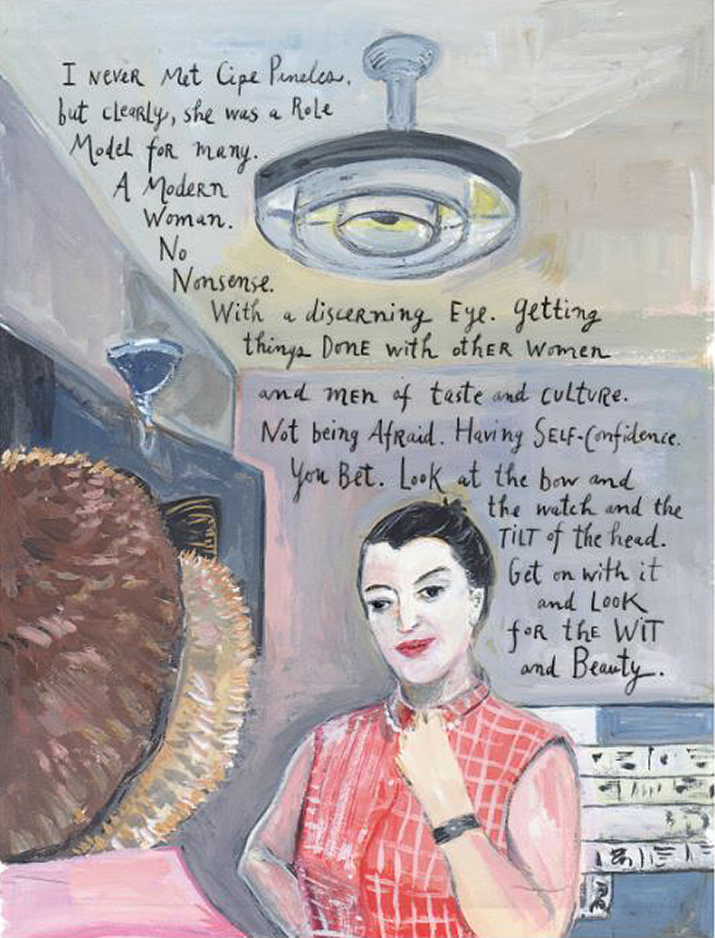

Pineles was among a small group of torchbearers in the early 20th century design and publishing industry that was breaking that mold. At Harper’s Bazaar there was editor-in-chief Carmel Snow, fashion editor Diana Vreeland, and photographer Louise Dahl-Wolfe (FIT had an exhibition on their collaboration); the movie industry had the famous costume designer Edith Head; the movies themselves had Maggie Prescott, editor of Quality magazine in the 1957 Fred Astaire and Audrey Hepburn film Funny Face. I’m sure there are more—we just don’t know them yet. But it takes detective work to bring unsung designers—and their contributions—to light. It is through such efforts on behalf of Sarah Rich, Wendy MacNaughton, Maria Popova, and Debbie Millman, that Cipe Pineles’ legacy was unearthed. It seems a fitting irony that it was done through this cookbook, Leave me Alone with the Recipes: The Life, Art, & Cookbook of Cipe Pineles, which inextricably combined the professional and personal for publish.

“Visual impact was the raw material for Pineles’s work,” said Popova in her contribution to the book. And the outcome? For one, it might get the reader to open a book they’d otherwise put back on the shelf. But Leave Me Alone with the Recipes is also an heirloom of design’s past, allowing for rediscovery of, as Rich describes, a “woman, whose work we’d never seen, whose name we’d never heard, [and who] nevertheless shaped how we draw, design, and even exist as women.”

© Maira Kalman