1.

My father wanted to be a writer. He could recite TS Eliot’s “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” and he revered Shakespeare. But aside from the elegant memos he wrote as sales manager for WNBC New York, which gained him respect in the slug-‘em in the face world of advertising in the 1960s and 1970s, he didn’t write anything at all. Or so I thought.

When I was in high school, and was complaining about an essay I had to write about The House of the Seven Gables, he told me that he had once written a “Talk of the Town” piece for the New Yorker. I didn’t believe him. The New Yorker was a towering edifice of cultural excellence and my father, being a man of commerce, had no place in it. I went to my room and struggled through my paper.

The next morning I showed it to him. He read it through and looked up. “Adam”, he said, “you write in clichés.”

2.

Years later, he was lying in a hospital bed in the middle of our living room, dying. He had Parkinson’s disease and it had been a slow decline. He had recently requested that his feeding tube be removed, so now it was just a matter of weeks.

Sitting by his bed, talking about everyday minutiae, which I thought he wanted to hear, but which was really a way to selfishly console myself, I remembered his reference to the New Yorker.

He couldn’t remember the year it was published but it was before he was married in 1962. The piece, he said, was about the Museum of Modern Art. I still didn’t believe him.

I searched through the digitized archives of the New Yorker. In the 1950s and early 1960s “Talk of the Town” pieces were unattributed, so I searched for references to MOMA. Eventually I found something that seemed likely in the June 25th, 1955 issue.

Somehow, during those grief struck days before he died, I managed to get hold of an actual issue. I sat by his bed and turned the brittle pages. “The Wistful” was the heading, and I read the following out loud to him:

The Museum of Modern Art is currently holding a display of East Indian weaving and ornamental arts, and one of the features of the exhibition is an arrangement of silken scarves and Indian utensils suspended over a wide pool of water. Beneath the surface of the water are some Indian bowls. We were fascinated on a trip to the Museum one day last week to observe that a lot of pennies and occasional nickels had been scattered around the submerged bowls. When we asked a curator about this, he told us that the Museum just can’t stop people from using the pool as a wishing well. Right now, the porters are making eighty cents a day from the penny tossings, and one enterprising fellow has been trying to up the ante by placing a suggestive dime in the pool each evening.

He had indeed published in the New Yorker. I was ashamed; I had doubted my own father.

Looking over at him in his hospital bed, my eyes dewy with remorse, I asked how it felt to hear his words after so many years. A conspiratorial smile whipped across his face.

“I made it all up”, he said.

3.

After his retirement from NBC, my father would get dressed every morning, impeccable in his ironed shirt and pressed slacks, eat breakfast, and then ascend the back stairs to his home office. My mother worked during the days, and so, we thought, did he. But we didn’t know on what.

After he died, my sister and I went through his office. We found talismanic objects (a brass compass, a cat with a marble eye, a collection of magnifying glasses), some telling books (Overcoming Procrastination) but no memoir of his life in the advertising world, which I had secretly hoped he had been writing.

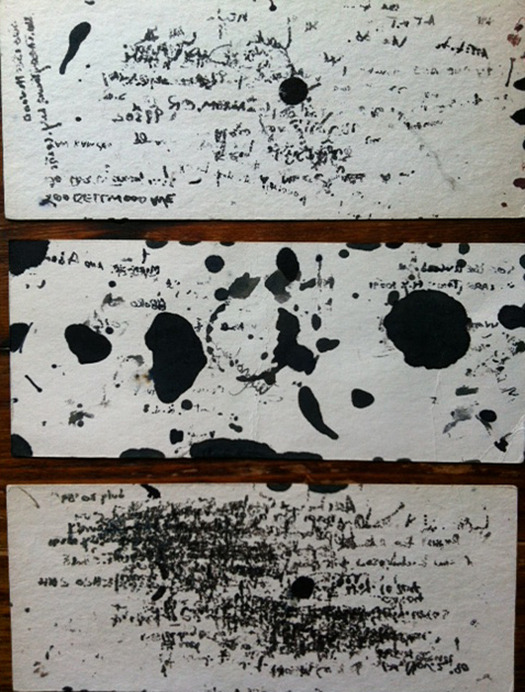

My father always wrote with a fountain pen. It was one of his trademarks, along with his bow ties and herring bone jackets. As we dug through the bills and papers on his desk we discovered, at the bottom of a pile, something beautiful and unexpected: his blotting papers.

Here were marks and scratches and inky blobs that any Abstract Expressionist painter would be proud of, an inadvertent vernacular art, stunning pieces of unintended graphic design.

My father was a man of deep good sense. He knew who he was: primarily, a family man. It what he loved the most. But how to make sense of all those hours in his office?

I always thought he wanted to be a writer but I was mistaken. In retrospect, I think it was me who wanted him to be a writer. It’s somehow appropriate that his written legacy, apart from the invented “Talk of the Town”, is illegible — letters in reverse and traces of words: were these his “to do” lists, or notes to himself, or his secret thoughts and dreams?