Photo-collage ad for photographer Marian Adreani's website, Arles, France, 2013. Photograph: Rick Poynor

Toward the end of Collage: The Making of Modern Art, published in 2004, art historian Brandon Taylor posed a critical question. “Has the Internet,” he wondered, “made collage more or less important as an instrument of contemporary aesthetic work?”

At that point, the answer seemed to be that if we apply a rigorous definition of collage as a process of physically cutting and gluing together image fragments to make a new image, then rather less of this was likely to happen in a digital age. If, on the other hand, we interpret the collage principle more liberally, then the evidence, Taylor concluded, already suggested that computer collage would proliferate for as long as software came with “cut” and “paste” commands. Within only a few years of this cautious assessment, collage of every kind — paper-based, digital, and all points between — is rampant. Some of this collage-making is finding its way into commercial projects, but there is also plenty of personal work by designers and illustrators who are passionate about collage. Cutting Edges, published by Gestalten in Berlin, assembles an international art squad of scissor-wielding collage enthusiasts and provides the perfect opportunity to take the measure of the resurgent medium.

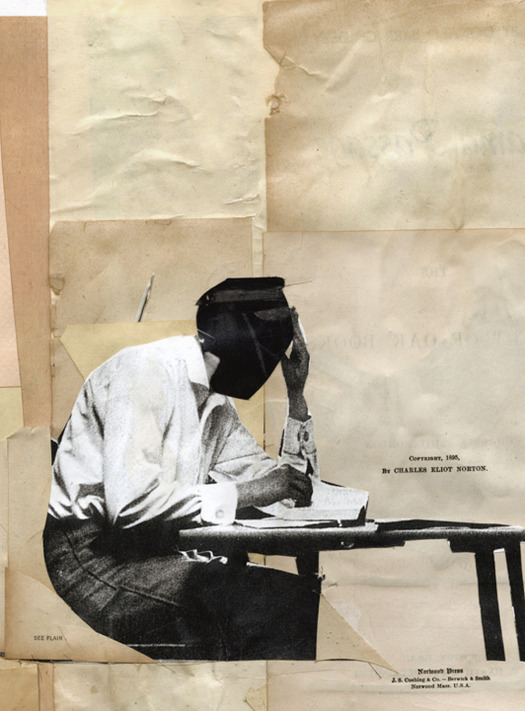

James Gallagher, Domestic 2, collage, 2010

The project’s coordinator, James Gallagher, a creative director based in Brooklyn, who studied at the School of Visual Arts, is a compelling collage artist in his own right, as well as being the curator of the “Cutters” series of exhibitions in Brooklyn, Berlin and Cork. Gallagher argues that collage is the perfect medium for coming to terms with a culture saturated in images, both printed and online. “Today’s collage artists carve out fragments from this frenzy and force the disparate pieces to become one,” he writes. “It is their way of controlling the chaos — or at least pushing the pause button long enough for examination.”

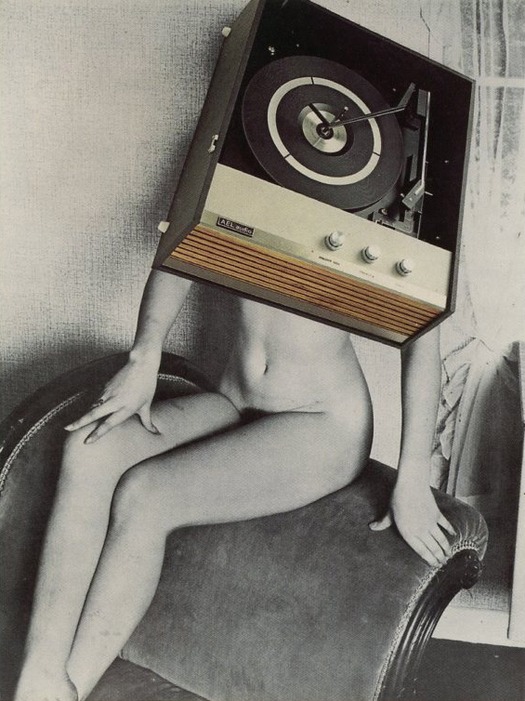

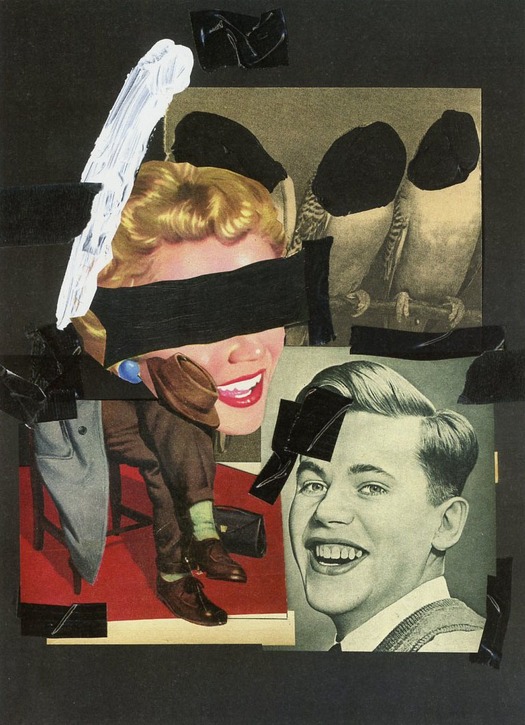

Linder Sterling, Pretty Girl, collage, 1977

Perhaps that explanation sounds too pat, but it does appear to be a primary reason why collage never went away for long and has now returned in force. In his history of collage, Taylor addresses the role the medium played in the development of modern art throughout the 20th century. While he touches on collage’s popular uses, which emerge in the 1960s counter-culture and develop through 1970s Punk, the wider uptake of collage in popular culture, particularly commercialized popular culture, lies outside his sphere of inquiry. Yet it’s here that collage now seems to have found a home in work that, for critical purposes, falls inconveniently into the buffer zone between the increasingly tricky to differentiate camps of art and design.

Oddly, despite assembling an arresting shop window of new projects, Cutting Edges does little to put the trend in context. The book’s main introduction simply rehearses the art historical development of collage from Cubism and Dadaism, through Surrealism, to Pop, the Situationist International artists, and Punk. There is no attempt to connect this to the new work in the book. Nor does the survey structure, with one collage-maker following another in a spectacular, un-signposted parade, make any critical distinctions between different forms of collage. It would be expecting too much for the compilers to venture any evaluative judgments — that’s not in the spirit of such enterprises — but the book’s presentation of everything on broadly equal terms, though some artists get more pages, certainly prompts the question: is all of this work equally good? With a method this open to all-comers, what qualities make for a good collage?

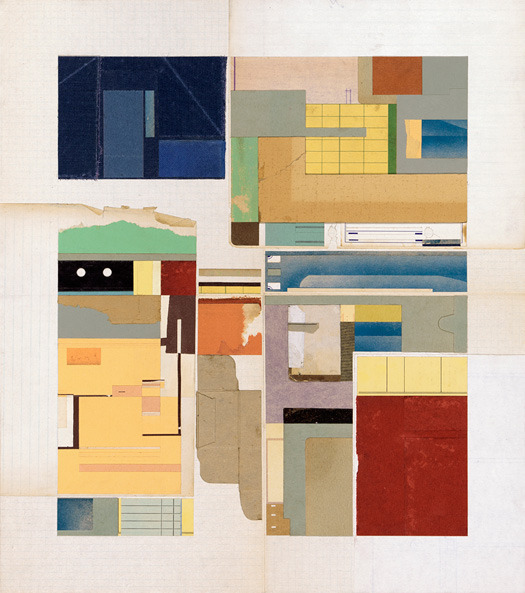

Almost every collagist in the book loves old imagery: anything photographed or printed before 1960 comes with an instant retro frisson. Any collage using such material is potentially likeable, but that doesn’t make it original or cause it to vibrate with commanding inner power. Many of these new generation collagists don’t know when to stop. They find source images with potential and bury them in mismatched clutter. A surprising number seem content to float elegant figures of fantasy, fine gentlemen and beautiful ladies, against decorative backgrounds pieced together from colorful snippings. Many compositions amount to little more than mute simulacra of earlier, better collages (Dada, Surrealism, and Pop cast very long shadows). A simple love of old bits of paper is rarely enough to imbue a collage with a feeling of necessity, though Canadian graphic designer Jacob Whibley’s intricate constructivist paper abstracts prove it can be done.

Jacob Whibley, Mass 4 (oo—), collage on panel, 2012

The most convincing collagists show an obsessive focus in their image-making. According to an interview in Elephant magazine, which ran a survey of 17 collage artists in its winter 2011 issue, Gallagher’s preferred sources are, he says, “Vintage photo books, sex manuals, clothing catalogs, text books, anything that can be folded into my world.” His collages usually feature one or two monochrome figures, their faces always concealed, set against open backgrounds built up from layers of paper to suggest abstracted interior spaces. A restricted palette and sparing use of random lines of type help to define his private graphic world. His aim, he says, is to reveal a zone of hidden behavior — its beauty, ugliness, solitude, and desire. There is an obvious connection here to the work of Linder Sterling, a British Punk-collage pioneer with a debt to Dada, who can make an unforgettable statement about sexual politics by placing an old mono record player over the head of a black-and-white nude torn from a men’s magazine (see above).

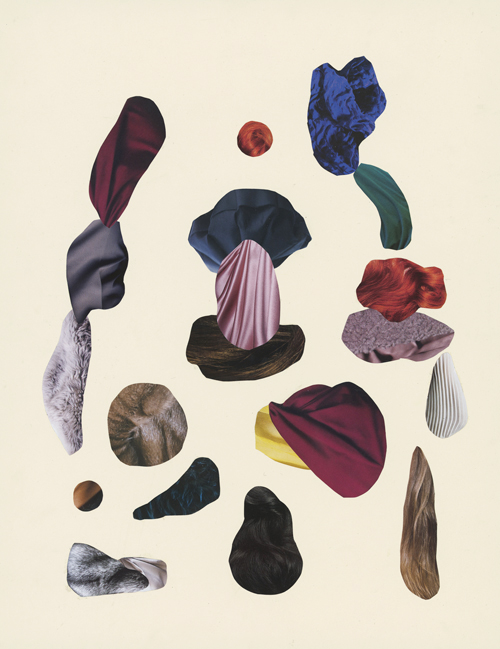

Malin Gabriella Nordin, Vacation, collage, 2009

Collages by Sergei Sviatchenko (Denmark), Malin Gabriella Nordin (Sweden), and Paul Burgess (UK) share Sterling’s and Gallagher’s concentration on particular types of imagery and methods of visual treatment. Nordin composes careful arrangements of stone-like precious objects cut from lustrous fabrics; Burgess edits and over-paints bright early 1960s advertising to imply darker relationships and undercurrents; and Sviatchenko, working in three dimensions, positions crude cut-outs of photos from revolutionary Russia against jarring pink and pale blue backdrops.

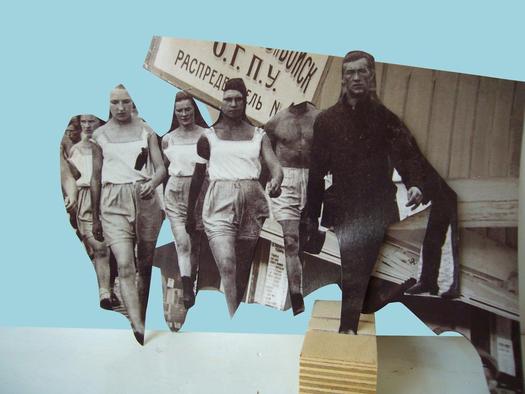

Sergei Sviatchenko, The Parade, 3D photo-collage, 2009

Paul Burgess, Three Bird Chorus, collage, 2010

Brandon Taylor ends his history wondering “whether collage in any of its older senses of displacement and rupture will find other ways of continuity, but by other means.” The answer provided by Cutting Edges is more straightforward than we might have expected. The bottomless ocean of imagery available on the Internet gives collage-makers even greater reserves of ready-made material to filter, borrow, and manipulate, while any paper image can be digitized by scanning. Many of the digital collages that result from these processes look no different from paper collages. The aesthetic stasis in so much contemporary collage expresses an understandable nostalgia for print, even among younger artists, rather than an unqualified embrace of digital collage as a tool for responding to 21st-century modernity.

One of the most distinctive artists in Elephant and Cutting Edges is Julien Pacaud, a French illustrator who planned to become a filmmaker before discovering collage. Pacaud’s use of displacement and rupture is so complete — he only works digitally — that I wonder whether “digital collage” is even the right term for what he does. He blends his source images seamlessly into pictorial scenes that might, as he says, belong to an imaginary film. Whatever the people were doing when he extracted them, they become actors in a new hyper-real drama. In one image, an Edwardian lady looks reverently at the grass, while another woman in the distance, holding hands with a companion, points to the sky where two huge planets hang above slender monoliths of light. Pacaud can sometimes overdo the portentous geometry (cubes, pyramids, spheres) but his re-colorized images look like fully contemporary visions and he is in constant demand as an image-maker.

Julien Pacaud, When You Sleep, digital collage, a response to the song by My Bloody Valentine, 2010

This essay was first published in Print magazine in June 2011. This is its first appearance online.

For more on collage, see also:

Collage Now, Part 1: Sergei Sviatchenko

John Stezaker: Images from a Lost World

Andrzej Klimowski: Transmitting the Image

The Art of Punk and the Punk Aesthetic

John McHale and the Expendable Ikon

An Unknown Master of Poster Design