A few months ago, an architect friend referred me to Stephen Talasnik, an artist of considerable energy and charm who creates dense, mesmerizing works in two and three dimensions. New Yorkers may be familar with his idiosyncratic portfolio from one of his many exhibitions here or from his recently installed work at Storm King. That initial introduction led to my contribution of an essay to Talasnik's new book, Floating World, a documentation of his installation of extraordinary bamboo islands at the Denver Botanic Gardens. These pieces, all meticulously assembled by hand out of bamboo, are held together by repurposed military restraining ties. To follow is an excerpt of my piece from that book, which I hope conveys the intelligence, generosity, and visual pleasure of both Talasnik and his work.

If you happen to be looking for it, you will find the studio of Stephen Talasnik in the depths of a century-old cast-iron building a few blocks from Canal Street, in Lower Manhattan. Ring the buzzer at the front door and the artist himself is likely to come and fetch you. Talasnik is a man of modest height, sturdy build, and boyish exuberance, though he is north of fifty and decidedly gray at the temples. After the usual pleasantries, he will guide you down a long and precariously steep stairwell — the kind architects can no longer slip past the building department — and through a dimly lighted basement hallway stacked to its rafters with crates and packing boxes and plastic garbage bags spilling over with the detritus of minor industrial production, the whole looking as if it might collapse at any moment.

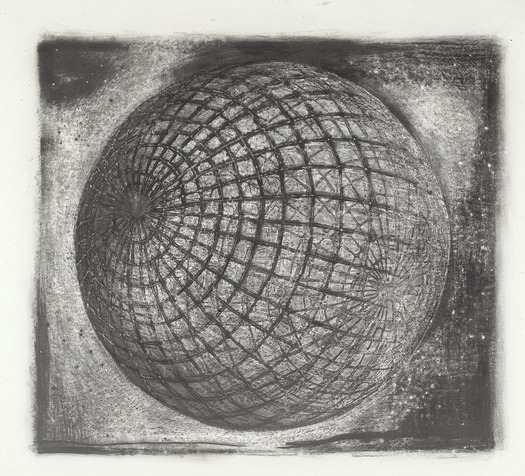

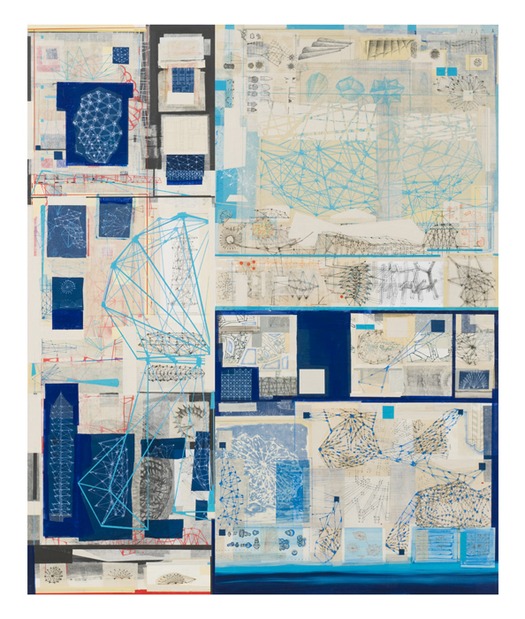

It is not the most auspicious introduction, and that little voice that lives inside your head may begin asking what exactly you’ve gotten yourself into. And then, at the end of a grim umbilical hallway, Talasnik opens a large steel door, beckoning you into a most unlikely Narnia. Before you is a studio that is bright and clean and open, and it stretches back far beyond what you might think possible. This limpid Neverland is populated by Talasnik’s sculptures, dense matrices composed of wooden rods and struts, and these are suspended from the ceiling and perched up on tables in various shapes and sizes and states of completion. On the wall to one side is a suite of drawings: thick sheets of abraded paper marked by patterns and grids that swoop and loop about in broad movements. Toward the rear, leaning up against a tall bookcase, are finished works in frames returned from a recent exhibition: collages that depict imagined alternate worlds with runic geometries and blueprints of impossible architectures.

Standing before this most unlikely vision, you now realize that Talasnik retrieved you from the building’s threshold not so much as a matter of hospitality, but to usher you safely into his sequestered basement realm. It may also occur to you that this passage, from the rude world of the everyday into a unique space of the imagination, is a not-so-subtle metaphor for the experience of coming upon one of Talasnik’s works, each one being a universe unto itself. If you glance at him, it is quite evident that Talasnik takes some considerable personal pleasure in delivering this transformational experience; indeed, that just might be the ultimate project of his work.

It is part of their strange fascination that Talasnik’s sculptures invite metaphor at the same time that they resist it. What are they, exactly? They appear familiar, but they are also opaque, though not in the maddeningly academic way of some contemporary art. Is that a ship’s frame or a roller-coaster? A dinosaur skeleton or a bridge to nowhere? Maybe a runaway tumbleweed or a collapsing scaffold? Their gridded forms are reminiscent of conceptual work of the 1960s and 1970s, but they are absent the hyper-seriousness and relentless perfectionism characteristic of that period. In Talasnik’s words, they offer “clues without plausible visual solution,” the result being an intriguing but pleasurable sense of destabilization. They seem like the works of an engineer — they have an “intuitive sense of geometry,” according to Talasnik — but an engineer’s work is nothing if not functional, and Talasnik’s sculptures have no practical function, beyond aesthetic satisfaction. They also seem visually precarious, even if they’re quite well constructed.

Talasnik did, in fact, study engineering — for all of one evening. After taking up sculpture, he enrolled in a course in mechanics at the Cooper Union, the first lecture covering the structural advantages of triangular systems. That information offered enough grounding for the work he was doing, and he thereafter dropped the course. Today, he is often asked whether he designs his sculptures with the aid of the kind of advanced computer software used by architects and engineers to model the most complex structures. He does not. Though their intricacy suggests otherwise, Talasnik’s sculptures are in fact created by hand from the artist’s imagination alone, a meticulous and sometimes tedious process. “I’ve never planned a sculpture. I start and see where it goes,” he says. “It’s a leap of faith.”

Talasnik began constructing his first sculptural works barely a decade ago, while sitting at home watching television to kill time. He never quite knows when his pieces are done, and is apt to quote a maxim sometimes attributed to Leonardo da Vinci on the subject: “a work of art is never finished, only abandoned.” That his sculptures are always in the process of becoming makes them, at least to him, all the more compelling. Referencing another Renaissance master, he notes that he prefers Michelangelo’s unfinished slaves, which seem to be bursting into life from inanimate matter, to his completed David. “The only thing that gets me to finish a sculpture is an exhibition or if someone buys it,” he says. He calls the studio, with its many works in progress, a “museum of patience.”

Talasnik’s early work was largely done on paper, not in the round. He came to sculpture through his drawing practice, and he turned to it — erroneously, as it turns out — because he thought he could produce sculpture more quickly and easily. His mode of conceiving sculptural work, nevertheless, is very much indebted to his practice in that two-dimensional medium. “It’s a drawing aesthetic, not a sculptural aesthetic,” he says. “It’s the reverse of chiseling away from a block of stone — it’s accretive.” His pieces typically begin with square frameworks of light wood (typically bass, bamboo, or birch dowels that he orders in large quantities online) that are held together with glue, like model airplanes. These lattices are then dipped, multiple times, into buckets of black or slate colored acrylic paint that the artist infuses with bits of graphite or gravel for texture. Several frameworks might be combined into a larger piece, and then dipped again, and the whole piece is typically given a final patina coating that leaves it with a neutral, matte finish. “How something is made is as important as what it looks like,” says Talasnik, a philosophy he attributes to and shares with the architect Frank Lloyd Wright.

One suspects that it is Talasnik’s ability to be serious without taking himself too seriously that accounts for his success. He has an irrepressible, optimistic energy, and conversation with him has a tendency to accelerate along rapidly, dipping in and out of the various subjects that fascinate him and serve as inspiration — say, the history of World’s Fairs, or the films of Werner Herzog, or the voyages of Ernest Shackleton (for which he has imagined an opera, complete with a set design of cantilevered wooden scaffolding).

These topics reveal Talasnik as a man of romantic imagination. There is, in fact, a certain grandiosity to his vision, even as the pieces he makes are painstakingly constructed by hand. It seems only fitting that his sculptures, so architectural in nature, are beginning to take on architectural scale, growing beyond the bounds of the studio, forming ever-larger agglomerations that create ever more complex relationships with their surroundings. The object, he says, is “not to imitate nature, but to create something new through personal experience.” Both his, it would seem, and ours.

-@marklamster