In 1898, at the request of then-president William McKinley, a volunteer cavalry was assembled to assist in the war efforts of the Spanish American War. Under the direction of Lieutenant Colonel Theodore Roosevelt, the regiment — which would be known as the Rough Riders — consisted of cowboys and hunters; gamblers and miners; Native Americans and college athletes. Among them was a young aspiring journalist named Samuel Weller.

Highlights from the papers of Samuel Weller, which were auctioned a year ago by Bauman Rare Books.

Back in New York after the War, Weller wrote briefly for the New York Sunday News, and eventually, became the editor of The New York Review, a theatrical journal published by the Shubert Brothers. In 1899, he met a sixteen-year-old aspiring opera singer named Hortense Kellogg, who, like Weller, had come east three years earlier — he, from Texas and she, from California — in search of glamour and excitement and fame. “Neither of them could imagine a life lived outside the enchanted circle of the theatre,” observes biographer Harmon Smith. “To exist otherwise was to be condemned to a dull purgatory.”

By 1901, Sam and Hortense were engaged. They married soon afterward and had four children in five years, the youngest of whom they named Frances.

All of the Weller children were artistic. Cedric, the eldest, was an actor; Gwen a sculptor; Beatrice a harpist; and young Frances, a dancer. Their mother, who took the professional name Hortense D’Arblay, was a lyric soprano who initially resented her family for interfering with her own artistic ambitions. Her own steely resolve with regard to a singing career was soon set aside, however, when she realized that her children could succeed where she had not.

For Frances, an artistic life meant concentrated study in dance. As a teenager, she studied at the Met Ballet School, and was admitted to their corps de ballet in 1922. She was sixteen years old, and highly motivated: within two years she would leave the company, joining the Russian choreographer Michel Fokine in the summer of 1924. In so doing, she proclaimed her newly-minted independence by jettisoning her first name in favor of her middle name, Carroll.

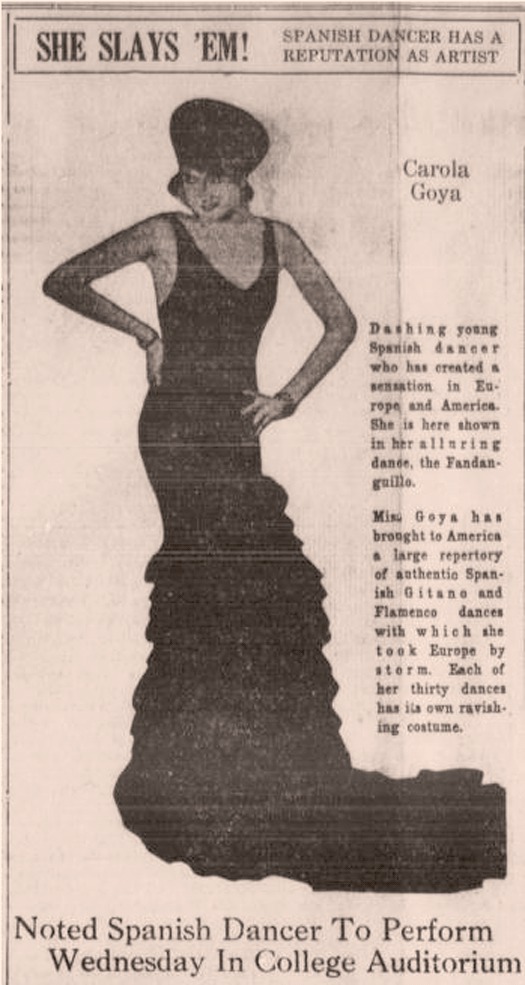

Three years later, as a wave of interest in Spanish dancing took over the New York dance world, she realized that this was what she was meant to do. In the spring of 1927, accompanied by her sister Gwen, Frances Carroll Weller sailed to Seville to study, having decided to become a Spanish dancer.

By the time she returned to the United States the following fall, she had become Carola Goya.

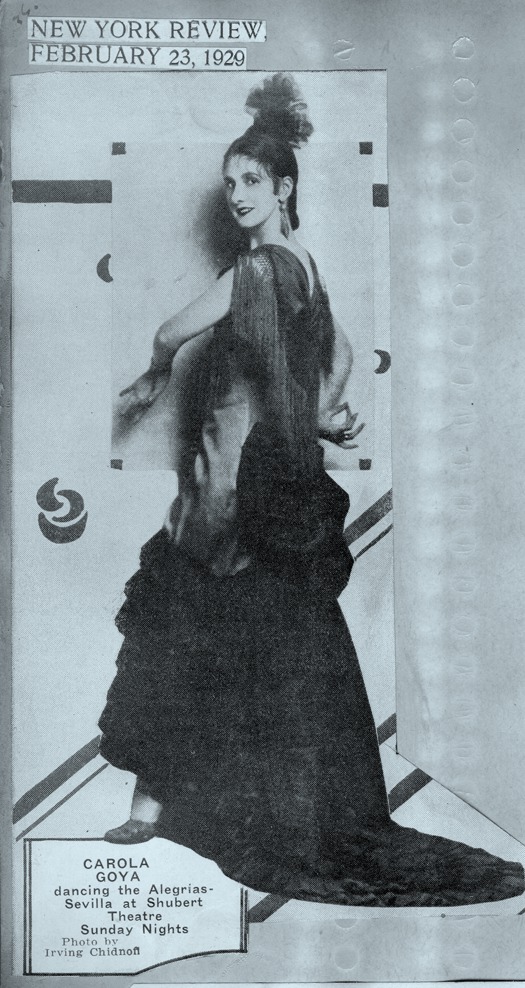

Carola Goya in 1929, the year she met Ezra Winter.

She was 21 years old and within a year, would enchant New York audiences with her beauty and skill. In a review in The Herald Tribune, the American critic Mary F. Watkins noted, “Miss Goya is young, exceedingly pretty, much in earnest and complete mistress of herself upon the stage.” Other critics called her "spellbinding"; "sublime"; and "a tonic for the eyes".

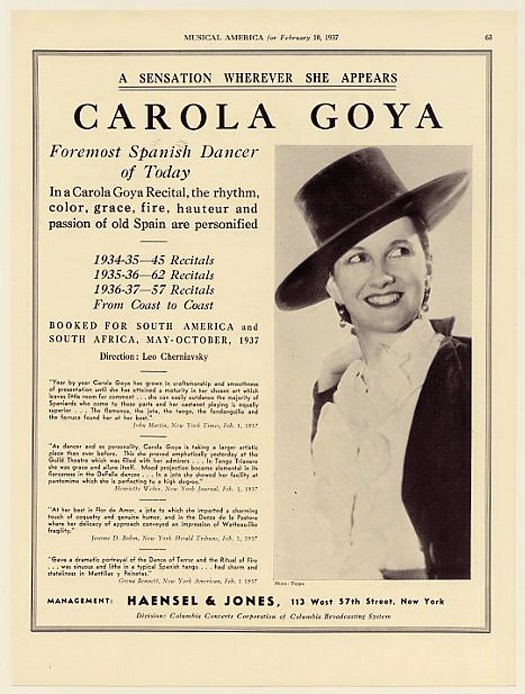

Advertisement in the magazine Musical America, February 1937

By 1931 Carola Goya would sell out Carnegie Hall, becoming the first dancer in history to do so.

Advertisement in The Daily O'Collegean, daily newspaper for the University of Oklahoma, 1933.

And yet, she came very close to ending her career when she met — and fell in love with — Ezra Winter.

Early in 1929, Winter held one of his large parties in his studio at Grand Central. Carola went with her sisters, and the artist was immediately drawn to her, suggesting that she pose for a painting, to which she eagerly agreed. He was 43 years old — twenty years her senior — and even though she swore that she was “bent on world conquest”, the young dancer entered into what would become her first sexual relationship.

He proposed. She accepted.

And then she told her parents.

(Please wait while the video loads.)

Both Sam and Hortense were outraged because of the age difference, but mostly, it seemed, because of the love affair's negative impact on their daughter’s promising career.

Three weeks after the stock market crashed in October of 1929, Carola Goya broke off her engagement with Ezra Winter, embarked on a multi-city European tour, and never looked back. A master of the castanet, she went on to become a great authority on Spanish dance, and was a founding member of the José Greco Dance Company. At the age of 68, she married her longtime dance partner, Matteo Vittuci. Goya died in 1994, in New York City. She was 88.

Within a year of Goya's desertion, Ezra Winter would find a new wife — someone more his social and intellectual equal, and closer to his age. But the dancer's vivacity paid dividends in other ways: Winter may not have been as hell-bent on world domination as his young mistress, but he was, in his own way, equally inspired by the call of beauty. He was equally driven by a kind of myopic, unbridled perfectionism. And he shared with the Spanish dancer a parallel preoccupation — indeed, obsession — with public recognition.

His devotion would soon pay off: within the next two years, Winter would work steadily, at once cementing his reputation and growing his bank account. He may have suffered in a personal sense, but in countless other ways, the muralist was enjoying an unprecedented amount of professional of success, success that would culminate, within the next 24 months, in landing not the girl, but the commission of a lifetime.

Comments [3]

09.01.12

07:14

I'm with Steven, when will this become a book?

09.05.12

10:15

I am writing a book on the murals of New York for Rizzoli. Presently I am working on the chapter for Radio City Music Hall and Ezra Winter in particular. There are a few questions I have for which the answers in your "Ezra Winter Project" won't be published until after my deadline so I would love to speak with you at some point in the near future.

Many thanks.

Sincerely,

Glenn Palmer-Smith

11.08.12

02:36