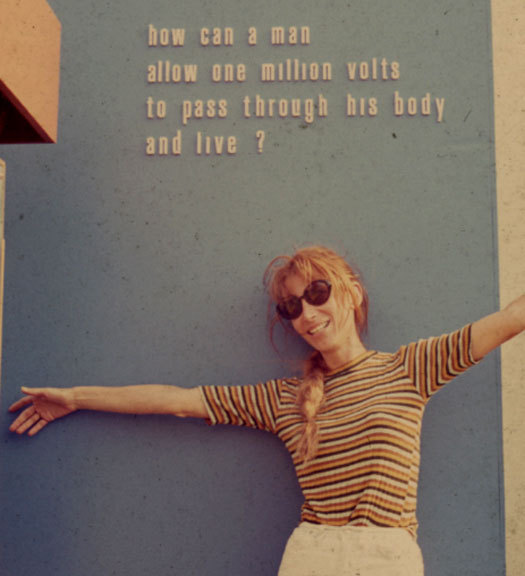

My mother Audrey, photographed in Montreal, about 1967

As a child growing up in the 60s, my mother didn’t look like anyone else I knew. When other mothers sported teased, bouffant hairdos, mine wore a braid over one shoulder and bangs. When others wore powder blue pedal pushers, mine wore black leggings. And when it came to my own really spectacularly bad 6-year-old taste — oh, how I wanted one of those crinoline skirts and a pixie haircut — my mother knew better, and quietly dressed my sister and me in Liberty print dresses with black tights, our long, straight hair cut in bangs like hers.

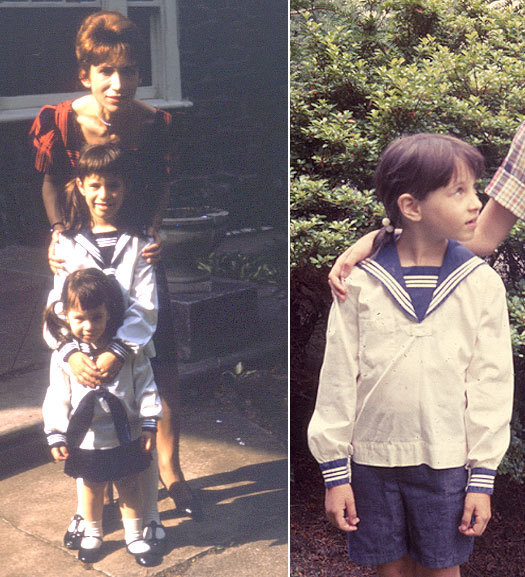

My sister and me in our Liberty dresses

It bears mentioning, I suppose, that Liberty hadn’t yet made a comeback (nor, for that matter, had bangs) and we looked nothing like our peers, many of whom delighted in pointing this out. My sister — four years older than I am — remembers an extended period during which we were dressed in matching sailor shirts, which our mother, bizarrely, found charming. (Ditto a pair of double-breasted — and belted! — English navy coats.) I can’t quite place the provenance of her nautical obsession, but as the following images attest, it went on for some time. (I'm probably two years old in the first image, and about six in the second.)

Examples of my mother's sailor (or "middy") shirt obsession

When the saturated color palette of those Kodachrome years spilled into the living rooms of my friends’ homes, ours was the opposite: elegant and spare, a chintz no-fly zone. Self-taught, my mother looked elsewhere for inspiration, and was an early devotée of what I’d later come to think of as the domestic mash-up: old with new, pattern against pattern, George Nakashima meets George Jensen. I have countless memories of her remaking things, a topic on which she was both fearless and agnostic: upholstery one moment, paper the next, she was as curious and comfortable working in two dimensions as in three. There were mismatched linens she’d restore by hand, chairs she’d refinish, frames she’d re-gild. At once whimsical and practical, my mother had a profound appreciation for eclecticism and because she didn’t know the rules, she held bravely to her own intrinsic sense of what worked and what didn’t. Some years later, when I received the formal education in design that she never had, I wondered which one of us was better off, and I was pretty sure it wasn’t me.

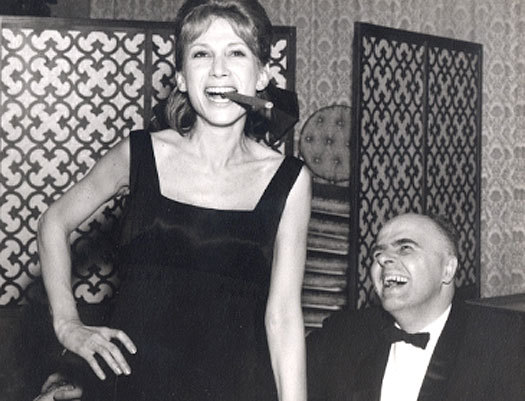

Where design was concerned, my mother was indefatigable: a passionate classicist, a committed modernist, she had a mind that never quit and the aesthetic fervor to match it. Back then, she was my adorable visual mother. Today, she’d be running her own design studio. My mother and father at a party in Philadelphia, about 1968

My mother and father at a party in Philadelphia, about 1968

In the days before the DIY revolution, it wasn’t so easy to make things unless you were either dexterous or entrepreneurial, and my mother was both. If she favored historical references, it was more as a provocateur than as a plagiarist: in her view, everything was grist for the mill, and she borrowed from everywhere. There was the time, for a friend’s wedding, that she yearned for a hat — the kind that the other Audrey wore — and not being flush enough to buy her own at the time, she found a basket for a dollar that she reshaped over a steamy stove. Indeed, on the Helfand-Hepburn issue, resemblance to her namesake was striking, requiring little effort on my mother’s behalf to make passers-by look twice. Let’s just say the hat was icing on the cake.

My Audrey (left) and the other more famous one (right) wearing the hat my mother copied

My Audrey (left) and the other more famous one (right) wearing the hat my mother copied

When I was about ten years old, our family moved to Europe, and suddenly my mother was the wife of an international corporate executive. If her wardrobe shifted into high gear, her essential attitude about herself did not: she was, after all, someone who had grown up during the Depression, and her sense of style had never been brand or label-dependent. Indeed, like so many of her generation, she was frugal beyond belief. She credited her beautiful skin to home-made facials made with witch hazel and wheat germ. She never once in her entire life set foot in a spa or, for that matter, a salon. The only thing my mother ever paid top dollar for were bed linens which, unlike fashion, do not date, and were, in her view, a justified investment. (I still have those linens. She was right.) She was not only smart, she was practical.

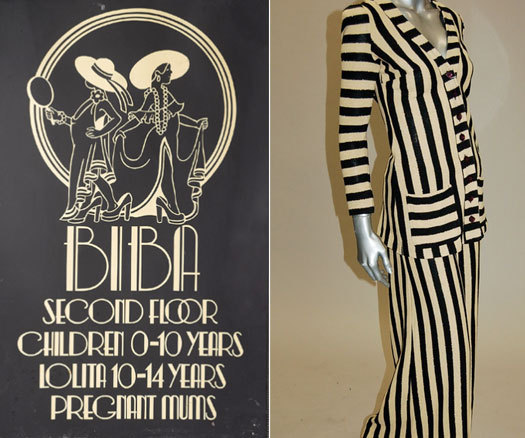

My mother was also, it must be said, extraordinarily feminine — in that way we think of movie stars from the ‘30s and ‘40s — and looked great in everything, particularly during the theatrical 1970s, when she discovered BiBa in London and Andre Courrèges in Paris. Long before the visual excess of Lady Gaga, my mother — by then in her mid-forties — had platinum hair and wore platform shoes. A woman ahead of her time. Left, Biba sign designed by Steven Thomas; right, a classic Biba ensemble in silk crèpe-de-chine (my mother had the polka-dotted version)

Left, Biba sign designed by Steven Thomas; right, a classic Biba ensemble in silk crèpe-de-chine (my mother had the polka-dotted version)

My mother saw design as art history writ large, and believed everything held an educational opportunity. It was Audrey who introduced me, as an eight-year-old, to the work of Charles and Ray Eames; Audrey who provided me with Froebel blocks to play with; and Audrey who bought me my first Aaron Copland record when all my friends were reading Tiger Beat. It is her fault that I am entirely too invested in Downton Abbey, having come of age, at her heels (did I mention she only ever wore heels?) watching romanticized British mini-series on television. It is because of my mother that I often see design as more about the past than the future because it is, after all as much an expression of who we’ve been than about who we will become. And it was under her influence that I grew to acquire a love of portraiture (the ultimate visual biography), beginning with painting but ultimately grounded in her collection of vernacular photographic portraits, many of them badges and pins of forgotten people. At my wedding, she wore them all.

Portrait of my mother taken by my father, early 1960s

Portrait of my mother taken by my father, early 1960s

It bears saying, finally, that my mother belonged to a generation of women who did not divulge their ages. (I would never have known how old she was had I not peeked at her passport once.) Untethered to such specificity, she was ageless — and like anything that is itself well-designed, timeless. She died ten years ago this week, and I think of her constantly: in my studio, in my garden, driving, drawing, thinking. We would all do well to be remembered as I remember her: for her intelligence and intellectual curiosity, her kindness and wit, but perhaps most of all, as someone who understood that design thrives as a function of the people who give it meaning. She taught me many things, but most of all, she taught me that.

Comments [7]

03.15.12

11:27

03.15.12

11:49

03.16.12

10:23

03.16.12

01:59

03.16.12

08:31

03.27.12

02:39

05.12.13

02:18