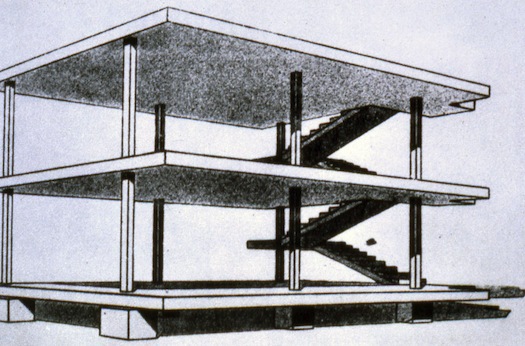

Le Corbusier, skeleton for Domino House, 1914–15

As we innovate on methods of service delivery at the Taproot Foundation, my colleagues and I frequently find ourselves grappling with the question of how to scale an organization so it is optimized for impact. As we explore ways in which other types of enterprises have dealt with this kind of growth challenge, it is tempting to remain fixated on an analysis of traditional organizational models — functional, divisional and matrix — in the quest to find one we could adopt.

Such organizational models emerged in the early part of the 20th century to prevent chaos and to promote efficiency in growing businesses. Unfortunately, management theory today confirms that these very structures can become so rigid that they often prevent creativity even as they preserve order.

This all got me thinking: how much structure does a small organization really need? In mulling over this question, I found myself thinking about the work of the famous Swiss architect Le Corbusier (1887–1965) and his distinctive plan libre.

During the early days of Le Corbusier's career, buildings were designed to reflect traditional bearing wall construction, which often limited the placement of interior walls. But LeCorbusier changed all that with his most iconic design and lasting legacy to the architecture profession: the Domino house. Conceived in the 1910s, it promoted a simple grid of structural columns supporting horizontal concrete slabs. This organizing armature allowed for a more important innovation to be realized: a "free plan" of undulating walls that could be placed in a variety of configurations to achieve spatial ingenuity. This was achievable because the walls were not limited by the structural grid, but rather enabled by it; as Corbusier noted in Towards a New Architecture, the grid became "the function that gives the form to the interior space."

To bring the conversation back to that other kind of structure — can we design nonprofits for efficiency as well as creativity? Can there be just enough structure in the right places to not only support, but also enable the kinds of human interactions that will help them operate as creative entities? In an ever-changing world, organizations of all kinds must be both strategically adaptable as well as operationally efficient. In the words of management guru Gary Hamel, writing in The Future of Management, we must "build organizations where discipline and freedom aren't mutually exclusive."

Organizations that enable some freedom of activity are naturally structured for creativity. They are often characterized less by prescribed roles, functions or departments and more by the types of human interactions their culture desires. Typically these are reflected in such things as a strong sense of community, interdisciplinary collaborations, a "one-team" mentality, and an open environment (both literally and figuratively).

When thinking about what kind of structure is the right kind of structure, we need to ask ourselves what kinds of behaviors we are trying to encourage so that our relationships — both internally and externally — deliver unique value and have real impact. Too much structure can mean too little freedom to explore and adapt. That’s something we need to prevent from happening.

Comments [8]

We might try to push the idea of structure so that it breaks up into types: for example, enabling structure and constraining structure. The former, at the risk of misinterpretation across disciplinary boundaries, akin to infrastructure. Then one might play with inter-structure (relationships with other organizations?), intra-structure, exo-structure (having entities and officers recognizable to outside). These are all just top of my head quickies: the point is simply to free us up to think about structure in new and varied ways.

The Le Corbusier example suggests playing around with structure as building blocks, tool kits, and the like. I'd even suggest thinking about organizational structure in terms of APIs.

I've been writing just this week about "organizational junk" (or debris) -- the organizaTIONal stuff that's leftover when organizations go away. It sounds negative, but my focus is both negative & positive : communities as places where organizational junk accumulates for better and for worse. The idea can be extended to "living" organizations: the "good" organization is one that regularly generates lots of organizational junk -- avoiding the mistake of trying to be too lean and mean, too efficient, to mission driven, too niche focused, too "zero-debris" -- because it is the stuff of adaptation, mutation, innovation, etc.

More later.

Dan Ryan

http://works.danryan.us

http://soc-of-info.blogspot.com/

07.05.11

08:27

http://www.jostle.me/solutions/bridge-silos/

07.05.11

08:38

thanks for getting the wheels turning!

07.05.11

09:37

"Less is More" but in management how do you know how much structure to delete before the roof comes crashing in? In architecture there are codes and regulations that determine, before hand, the minimum bearing capacities. In management there is no clean way to predict failure.

www.paulbyrnearchitect.com

www.greenappleclassrooms.com

07.06.11

12:40

But, as we humans tend to do, we've ignored the greatest teacher and best lessons resident in the world around us - nature. In nature, structure and organization is often quietly in the background, seamlessly integrated, almost passive to the present. Look at the efficiency, minimalism and economy within natural structures and systems. Look at the strength in just the right places, no more no less. Look at the flexibility, adaption and willingness to sacrifice. Look at the selflessness in the presence of powerful forces.

So as we look to the great Le Corbusier, perhaps we should also look to other great structuralists like Antoni Gaudi, or the whole biomimicry movement or that 80 year old tree in your backyard or the skeleton of a bird.

But no self respecting architect (even one who long since abandoned the profession) could comment on this subject without quoting the great Mies Van der Rohe who put it simply, "less is more." The laws of entropy, gravity, conservation of angular momentum, etc. govern all things whether we like it or not.

Like interfaces, the best organization is one that barely exists, rarely gets in its own way and may be very hard to actually design.

07.06.11

09:39

07.06.11

12:56

I recall my experience working on a summer camp project, where we had a simple flat structure with four functions and everyone took two roles to cover and assist each other. It worked well with only 4 core members.

The economic theory says the division of labor brings efficiency, but on the other hand, the generalists are in great need to operate at full capacity in a small organization.

07.06.11

02:01

In a hasty attempt to link this pedantic digression to the true subject of this article, I suggest that this highlights the tendency to focus on a few charismatic individuals over the cumulative efforts of many, and that this is one of the less helpful features of the traditional organisational model.

07.13.11

08:25