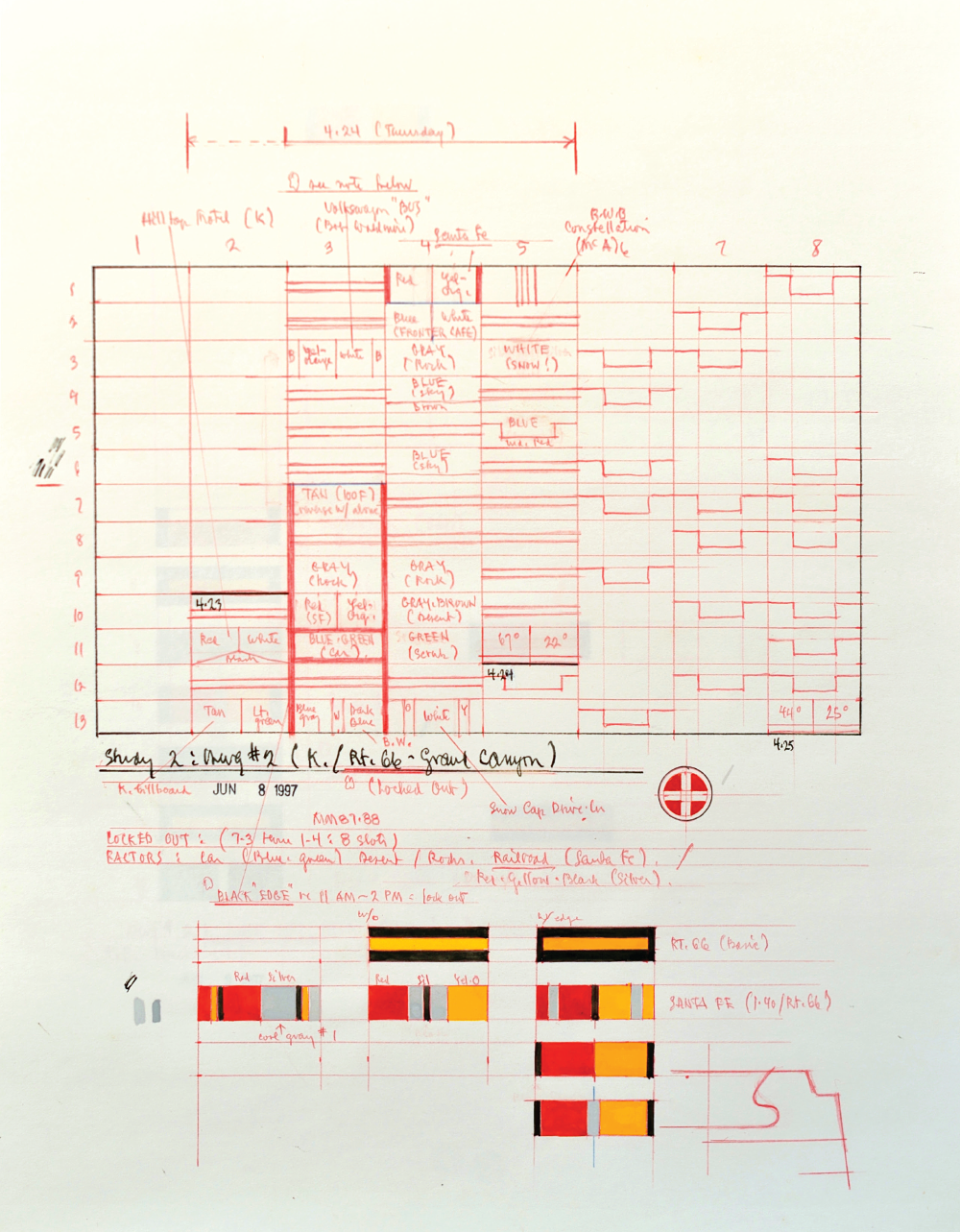

David Pease, sketchbook

Over a career that spans more than six decades, David Pease has built a body of work that is anchored by a methodical studio practice. Collections are ordered. Supplies are labeled. Folders—meticulously documenting the trips that provide the essential source material for the paintings in this exhibition—are date-stamped and alphabetized. There are lists (places lived, trips taken), not to be confused with inventories (postcards by category, sketchbooks by number), making his studio at once a cabinet of curiosities and a laboratory for experimentation. His interests are broad—from literature to architecture, bridges to baseball, A.J. Liebling to E.B. White—making everything, in a sense, grist for the mill. Pease’s studio walls provide an active surface for displaying both found and fabricated elements, inviting studies in parallel form and comparative juxtaposition—a Krazy Kat cartoon, a vintage color chart—observations that play out in delightful and perpetual flux. Here, the studio wall becomes a kind of kinetic canvas all its own, a seedbed for ongoing investigation, interpretation, and play.

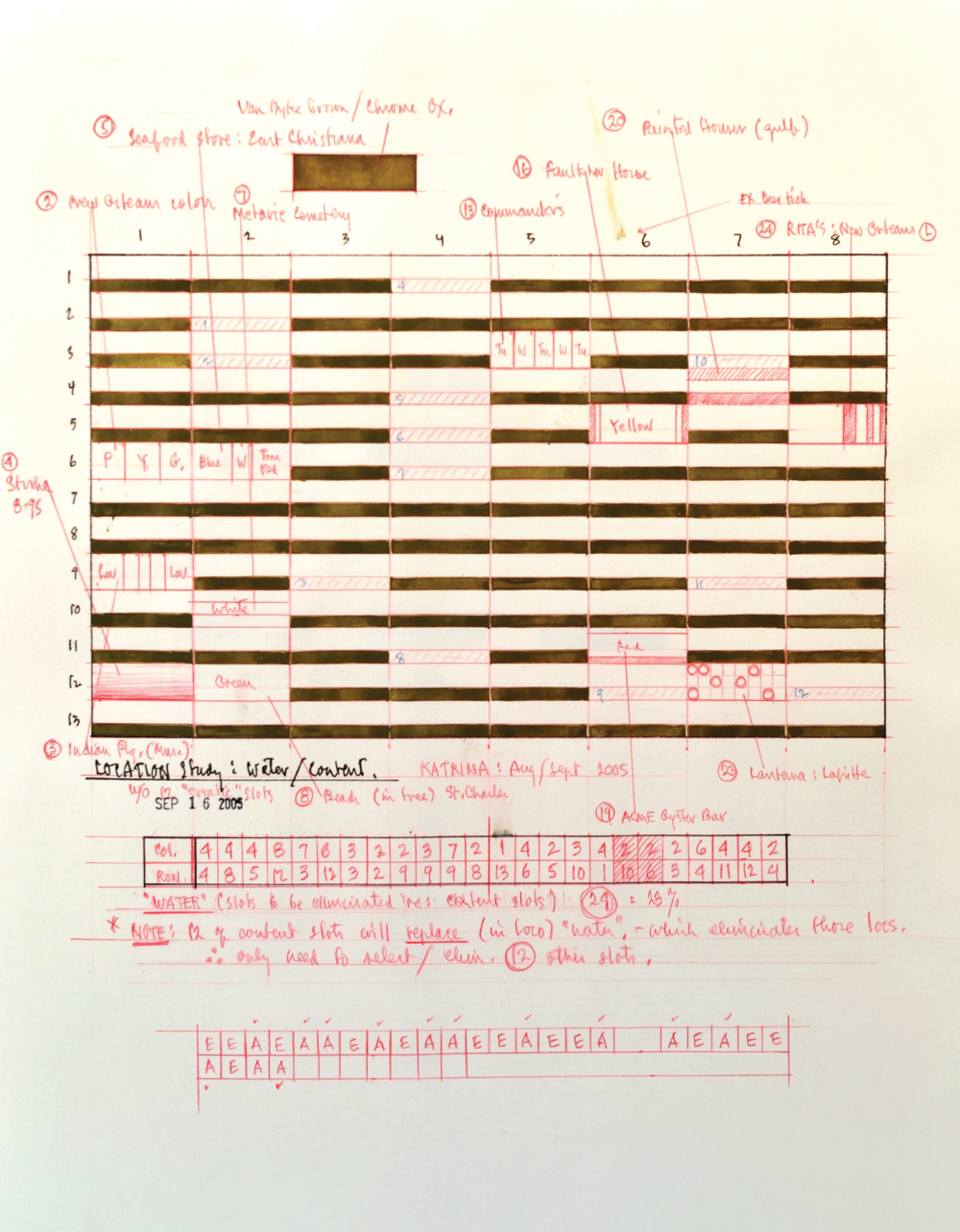

The studio is also home to a collection of sketchbooks that are, without question, worthy of their own exhibition. Dating back to the 1960s, these sketchbooks are deep repositories of visual ideas, tracking the artist’s evolution as a thinker and observer, educator and reader, collector and maker. Packed with meticulous detail, they’re also graced by a series of curious numerical codes, evidence of something Pease readily identifies as a “chance operation”—a nod to the sorts of experiments first introduced by Marcel Duchamp and later adopted by artists like John Cage, Robert Rauschenberg, and others. For Pease, “chance” translates to using assorted game pieces (a roll of the dice) to randomize and, in a sense, de-ritualize certain formal decisions. (The destabilized positioning of the tumbled slots in Katrina, for example.) As befits his orderly studio method, the results of these experiments are recorded in the sketchbooks with astute, laboratory-worthy precision.

David Pease, sketchbook.

It is here, in the sketchbooks, that many of the artist’s formal vocabularies are introduced and developed, and where the grid as an armature for study first becomes apparent. Pease somewhat humbly refers to his years as a dean at Yale, a time when the organizational imperatives of an administrative position obliged him to keep calendars and schedules which he insisted on creating by hand. (This is not a man who imports spreadsheets.) All of which became more grist for the mill: these handcrafted checkerboards became, over time, part of a rich visual grammar that would reveal itself in his sketchbooks, gradually evolving into this particular body of work.

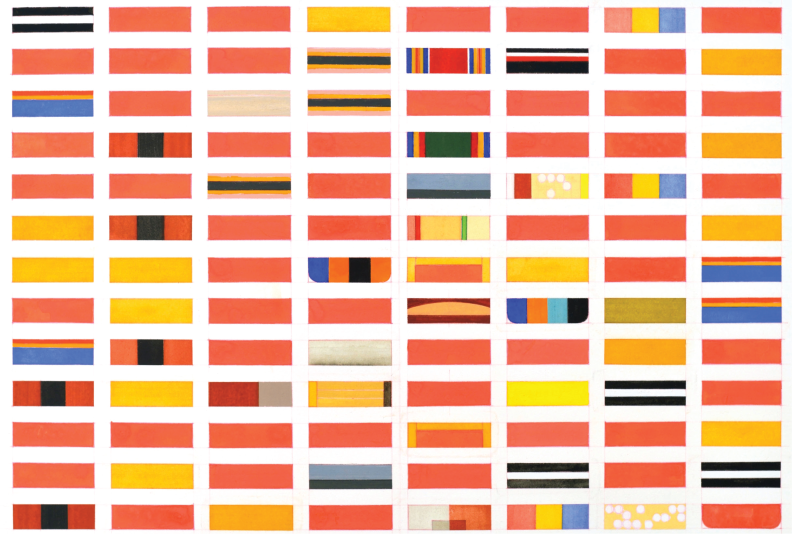

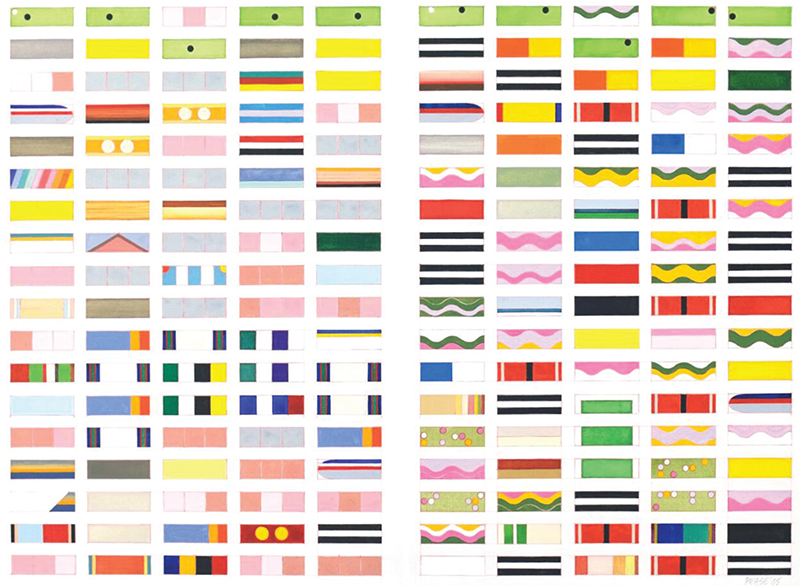

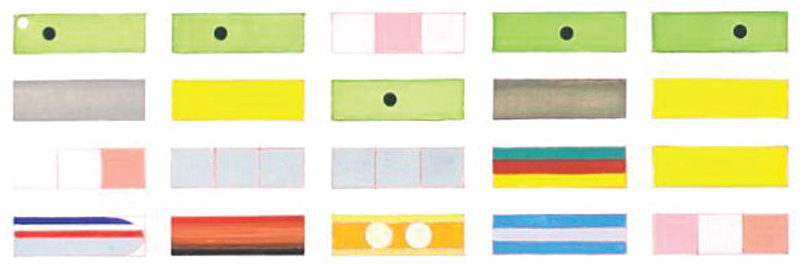

Pease occasionally paints “samplers” as studies (or, in his own words, “souvenirs”) for these larger works, crafting a smaller- scale preview of the larger painting still to come. In addition to questions about form, color, scale, and representation, he’s looking at time—speed and slowness, day into night—and considering how the individual moment meets the orbit of the broader journey. Here, form and content circumnavigate the artist’s recollections, creating a framework with a very particular visual gestalt, a graphic system that combines geometric certainty with chromatic variation, merging simplicity with serendipity, the constant with the variable.

Master Lawrie's Room, 2009.

Many years ago, Pease had the idea to locate a linen postcard on a larger ground, whereupon he would extend the image outward onto a larger field. These postcard paintings drew their distinctiveness from a simple juxtaposition: they reconciled a moment in time (the postcard) with a larger visual purview (the painting), thus challenging the physical boundary of the primary image. (This is pure Pease: take the thing, challenge the thing, create a new thing.) But there’s a more subtle intervention at work here. How do the boundaries of memory frame perception? How can a painting recalibrate our sensibilities, reframing the temporal against the actual, cementing the moment to the memory? Arguably, the postcard paintings may have foreshadowed the slot paintings in their focus on merging the anecdotal moment (time, place) with the formal gesture (paint, space). Then as now, the artist looks closely as well as aerially—at history and at the future—reducing the complexities and removing the deviations that stand between memory and reality, painter and viewer. The result is a magical orchestration of keen observation, subtle recontextualization, and superbly rendered detail. Pease is a visual memoirist with a finely tuned sense of how to tell a story. He is also, it must be said, an excellent editor.

In my own memory, I have a strong image of a studio, the smell of turpentine, the sweet rewards of graham crackers smeared with honey whip served with tall glasses of frosty milk. As a very young child, I lived across the street from David Pease, and his two daughters were my closest playmates. Many years later, when I was a graduate student here at Yale, he became my thesis adviser, and it was under his tutelage that I began, in earnest, to integrate my collecting interests with my writing and studio practice. Today, as I consider my next chapter, I look at David Pease’s work and consider what it means to spend a lifetime in the studio: to look and see, to travel and remember, to coordinate the dots that frame our own peculiar odysseys. In the end, all of us have our own “Key Incidents”: our travels marked by the sporadic recollection, recorded through the enduring, if not always reliable, prism of human memory. If we are lucky, such reminiscence is paired with reflection, the reflection itself a catalyst for making work, which is—it must be said—a reward in itself. David Pease agrees. “It’s not only what you have to do,” he observes with a dry, knowing smile. “It’s what you get to do.”

Shiloh: 8 Meals, 2005

Detail Shiloh: 8 Meals, 2005

This essay accompanies an exhibition at the Henry Koerner Center for Emeritus Faculty, Yale University 20 September to 21 December 2016. You can read part one here.