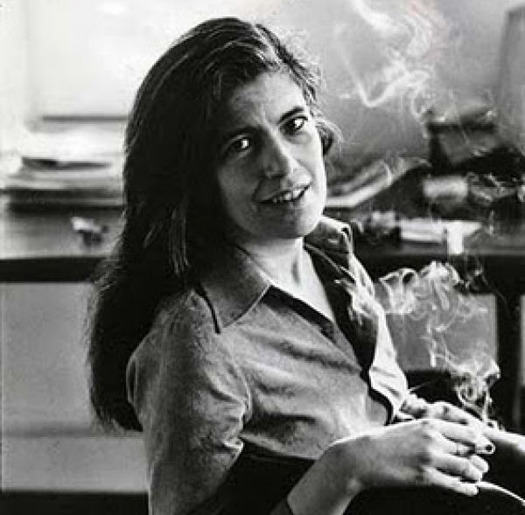

Photograph by Jill Krementz, from a print signed by Susan Sontag.

Over the years, as a designer, I have encountered an endless stream of CEOs, magazine editors, university presidents, and new media gurus — even a few Senators and a President. No one, however, scared me as much as Susan Sontag, who died yesterday after a long battle with leukemia. For more than twenty-five years I was her son's close friend, her occasional companion for dinner or a movie, and a fellow reader and book collector. I was never among her closest of friends.

But I was her graphic designer.

Susan was the most intelligent person I have ever met. She was intense, challenging, passionate. She listened in the same way that she read: acutely and closely. There was little patience for a weak argument. She assumed, often wrongly, that you possessed a general level of knowledge that would challenge even most college-educated professionals. She assumed you knew a lot and that you were interested in everything precisely because she was so interested in everything. Anything less left her unsatisfied, and, as she would not suffer fools, she wanted every encounter to be one in which she learned something.

Her interest in everything says a lot of my meetings with her over the years. There were early visits to her Upper West Side apartment in the 1970s, when I was still a young and impressionable student, in awe of someone who could own so many books (and who seemed to have read all of them). [The photograph above is from a print that hung in the Pomander Bookshop, our local bookshop in the 1970s. Long before it was popular, they specialized in the newest fiction from Latin America; Susan not only had read most of it already, she knew most of the the writers.]

My recollections of time spent with Susan Sontag have a great deal to do with her insatiable appetite for intellectual adventure, and perhaps it is this that has left its impression on me most of all. I remember a lunch in London, where she took me to a print shop and I bought two prints of Vesuvius by Sir William Hamilton. I would go on to collect volcano prints for another two decades, and Susan would later write The Volcano Lover, a novel based on the life of Hamilton. There were two Christmases in Venice, one spent in the company of the Nobel Prize-winning Russian poet, Joseph Brodsky, who took us on extended walking tours from church to church (anticipating his book on Venice, Watermark). Several years ago, we were at a wedding together in Washington D.C., and Susan insisted on stopping at the National Gallery of Art to see an Art Nouveau exhibition on our way to the airport. And just last winter, I met her to talk about a book project, but she rushed us off to the movies to see The Triplets of Belleville, the animated French film she had seen only days before. Finally, there was the recent dinner where she insisted, despite being weak from illness, on traveling across town for a feast by her favorite sushi chef.

Perhaps my most memorable evening with Susan was one when I came by to show her some book covers, and she invited me to stay for dinner. A mutual friend arrived, and Susan, who never cooked and seldom ate at home, served us dinner. It was all a set-up. She was so excited by some of her recent readings that she needed an audience to share her discoveries. Over dinner, she read us the first chapters of recently published books by Imre Kertész, Fleur Jaeggy, Anna Banti and Penelope Fitzgerald. She read aloud with a passion and urgency that eclipsed everything else around her. As dinner conversations go, it was, perhaps, a little one-sided. It was also an unforgettable performance.

*****

Susan Sontag will long be remembered for such enthusiasms, and I think it's fair to say that few writers have been as deeply involved or as influential in the cultural and political landscape of our times. Her apartment was full of carefully chosen objects, from many different periods and places, and her abiding interest in culture led to an appreciation of cultural artifacts. Mostly, though, she collected books: not as a rare book collector, but rather as the voracious reader she was. All of them were closely read and held, and at some point Susan came to care deeply about their design.

In the mid-1980s, Drenttel Doyle Partners designed a series of her books for Farrar Straus & Giroux. Susan had a favorite piece of art for each book. She always wanted to see what we'd propose, but it was hard to compete with what she had chosen, her selections suggesting, from her perspective at least, deep relationships to her writing. As a result, her first series was art-laden, boasting works by Isamu Noguchi, Andrea Mantegna and George Seurat. But there were also surprises: The Benefactor featured a work by Garnett Puett, a human form-like sculpture created by bee honeycombs, with the bees flying from New Jersey into the gallery in Chelsea, long before Chelsea had come of age as an art destination all its own. These books had all been published before, so Susan had had plenty of time for ideas and associations to germinate: and while the idiosyncratic art choices were generally hers, I learned a great deal in the process.

AIDS and Its Metaphors, our next project, was a new book and overtly a work about the language of illness. We used a passage from the book to create a typographic cover: "Infectious diseases to which sexual fault is attached always inspire fears of easy contagion and bizarre fantasies of transmission by nonvenereal means in public places." (Not an expected image; nor, perhaps, language that easily rolls off the tongue, but I think this cover was one of Susan's favorites.)

Fifteen years after this first series, Susan asked us to design a new paperback series of all her books for Picador. I agreed, with an unusual stipulation: the art on the book could have no meaning or association with the content. We worked with abstractions of images to create feelings and patterns and colors, and my conversations with Susan were purely about aesthetics — the beauty or sharpness or hue of an image. I used to look forward to these meetings: I think Susan loved getting lost in this unusual territory where content and language were less critical. While she was always the opera critic, I imagine seeing these covers were a bit like being awed by a beautiful stage set in the darkness of an opera house. This approach to bookmaking — less literal, highly subjective, even lyrical — was refreshing for me as well.

Earlier this year, Susan asked me to publish the speech she delivered upon winning the German Peace Prize. Literature is Freedom is a book I'm especially pleased to have made. In it, she writes: "To have access to literature, world literature, was to escape the prison of national vanity, of philistinism, of compulsory provincialism, of inane schooling, of imperfect destinies and bad luck. Literature was a passport to enter a larger life; that is, the zone of freedom. Literature was freedom. Especially in a time in which the values of reading and inwardness are so strenuously challenged, literature is freedom."

I have a more expansive view of the world from having read Susan Sontag's many books, from having worked with her as a designer and publisher, but mostly, from having known her. For so many of us, she was a lightning rod for ideas about everything: from illness and health to photography and painting to the politics of Vietnam, Bosnia, 9/11 and Iraq. In her writing, she insisted that we confront ideas in their full-fledged complexity. She deplored ignorance, and relished originality, creativity, imagination: but mostly what she championed was the importance of intelligence: "We live in a culture," she once wrote, "in which intelligence is denied relevance altogether, in a search for radical innocence, or is defended as an instrument of authority and repression. In my view, the only intelligence worth defending is critical, dialectical, skeptical, desimplifying."

As a designer, I relish every project I've done with her. She is my favorite author because she was so challenging, so fearless, so intelligent. She loved it all so much. And I loved her.

Comments [29]

I was put onto her in "Le Déclin de l'empire américain" by Denys Arcand (1986), where she was referred to - in a couple of lines - as _the_ female intellectual icon.

http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0090985/

Your blog is great.

12.29.04

06:00

12.29.04

07:59

Here she is, for instance, on the design vs. art debate:

But to define the poster as being, unlike "fine" art forms, primarily concerned with advocacy -- and the poster artist as someone who, like a whore, works for money and tries to please a client -- is dubious, simplistic. (It is also unhistorical. Only since the early nineteenth century has the artist been generally understood as working to express himself, or for the sake of "art.") What makes posters, like book jackets and magazine covers, an applied art is not that they are single-mindedly devoted to "communication," or that the people who do them are more regularly or better paid than most painters or sculptors. Posters are an applied art because, typically, they apply what has already been done in the other arts.

In the remainder of the paragraph, Sontag marshalls a long list of names from Toulouse-Lautrec to Cassandre in support of this thesis (which you'd be well-advised to read before mounting a disagreement), and all this is presented as almost no more than an aside in the much longer essay. By the end of the piece, she is confronting the fact that the book's Cuban revolutionary posters, concieved as anti-capitalist statements, are here being offered as their own kind of commodity. Few writers were able to look a contradiction like that in the face like Sontag.

I'm not sure what the book's publishers had asked for: a single page appreciation would have done just fine. Sontag's essay, instead, is over 10,000 words long; it is by far the longest piece in Looking Closer 3: Classic Writings on Graphic Design, where it was reprinted in 1999 (thanks to Bill Drenttel and with an introduction from another Design Observer, Rick Poynor). All this from someone who had never written, as far as I know, on graphic design before. We are fortunate to have it.

12.30.04

01:32

12.30.04

10:47

12.31.04

01:51

12.31.04

10:52

for an article on sontag and stage sets see:

http://carmenmirada.blogspot.com

12.31.04

04:17

a very specially exciting HAPPY NEW YEAR 2005

and we will go on what she did.....

since 1980 in Bonn bei Altmanns I loved her

so much, the person and the word

all she wrote to us

und wir sahen sie noch in der paulskirche 2003

FFM

herzlichst

Dorothea

01.01.05

10:46

01.02.05

02:28

I remember the first day. The man standing in front of the class looked ancient to me; he was probably all of forty-five. I was sixteen. He wrote "Mr. Burke" on the blackboard. Then he began talking about the approach to literary texts he would be using. I thought, "This sounds familiar."

I'd already been reading Kenneth Burke on my own for several years--I read a lot of criticism and literary quarterlies. After class I went up to him and said, "Excuse me, Mr. Burke,"--I was very shy and didn't approach a teacher easily--"I hope you don't mind my asking, but could you please tell me your first name?"

"Why do you ask?" he said. I have to explain that at that time Kenneth Burke was not famous. I mean, he was famous to a tiny literary coterie, but he certainly didn't expect any undergraduate to know who he was.

I said, "Because I wondered if you might be Kenneth Burke."

He said, "How do you know who I am?"

And I said, "Well, I've read Permanence and Change and The Philosophy of Literary Form and A Grammar of Motives, and I've read . . ."

He said, "You have?"

01.03.05

07:00

01.05.05

02:03

Persuasive enough though, evidently, to clear whatever the bar is on the Upper West Side.

01.07.05

09:56

I believe the mayor Muhidin Hamamdžić announced a street will be named after Susan along with a small memorial.

May she rest in peace.

01.08.05

01:57

01.08.05

02:23

01.09.05

01:39

It is the easiest thing in the world when genuine talent and insight is lacking to become political or write about something like AIDS. Not that she is any different from 1000's of other so called intellectuals.

01.11.05

01:17

Rain

Rain, midnight rain, nothing but the wild rain

On this bleak hut, and solitude, and me

Remembering again that I shall die

And neither hear the rain nor give it thanks

For washing me cleaner than I have been

Since I was born into this solitude.

Blessed are the dead that the rain rains upon:

But here I pray that none whom once I loved

Is dying tonight or lying still awake

Solitary, listening to the rain,

Either in pain or thus in sympathy

Helpless among the living and the dead,

Like a cold water among broken reeds,

Myriads of broken reeds all still and stiff,

Like me who have no love which this wild rain

Has not dissolved except the love of death,

If love it be towards what is perfect and

Cannot, the tempest tells me, disappoint.

—Edward Thomas (1878-1917)

From The Poems of Edward Thomas, Handsel Books (2003).

I cannot reprint it here because of copyright, but Mort de A.D. by Samuel Beckett was also read. This is a poem I would recommend to anyone interested.

01.19.05

06:57

01.22.05

08:00

01.22.05

07:26

Many smart people have disagreed with Susan Sontag, some have even become angry at her opinions, but no serious person would ever accuse her of being banal. When Marc says, "Not that she is any different from 1000's of other so called intellectuals," he reveals his own ignornance. There are not 1000s of real intellectuals in the world, and certainly not thousands or hundreds or tens of the caliber of Susan Sontag. That he would respond negatively to isolated quotes in my post suggests the limited scope of his reading.

Responding to Peter D is more difficult. Read the language: "dry-mouthed over-earnest upper middle brow pseuds dispensing fatuous tosh." Peter D has no point-of-view, no argument, except the trashing of writer who has just died.

Even if I disagreed with a writer, I would not casually respond negatively to a heartfelt remembrance of someone who has just died. What kind of person feels obliged to add their own vindictive voice to a post such as this?

The smart thing on a site like this would be to NOT respond to such animosity. We have a posting policy that allows me to remove such comments as "unnecessarily antagonistic, defamatory, foul." I choose, instead, to go on record: there should be a standard of decency for those who have nothing to say. Rather than ignoring your harsh words, I say go elsewhere. There are plenty of places on the internet for hate and ignorance.

Susan Sontag stood for the serious and continuous engagement with literature and war and illness and visual culture, among so many issues. Many of her friends disagreed with her, and would fight for their right to take another position. On one plane, however, her friends were united: a serious engagement with such issues requires intelligence, awareness of culture, and knowledge of history.

I hereby give warning to Marc, Peter D. and others of their type. I will take down unnecessarily antagonistic and gratuitous comments. This post was made to honor Susan Sontag. I do not care if you like her or agree with her, but if you do not have something intelligent to say, do not post.

01.24.05

02:05

My point had to do with literary and philosophical criticism. Everything Sontag said of significance appears to me to be derivative and I can immediately tell when she comes up with an idea of her own because it is the work of a lesser mind.

For example below are two quotes attributed to Sontag

"He who despises himself esteems himself as a self-despiser."

(Is attributed to Sontag and it is excelleent... but it is Nietzsche's idea)

"Any important disease whose causality is murky, and for which treatment is ineffectual, tends to be awash in significance."

(Is obviously Sontag's idea because she pontificates in a ponderous and obtusive manner what any 5 year old could readily tell us is)

This is merely my observation of her work. I am sure she was a very fine woman in many ways. If you want to remove a literary and philosophical criticism and call it "hate" that is fine. But what you ought to do out of intellectual conscience is restore my original post.

01.25.05

08:30

My orginal post was not deleted I see. It is above my name, not below.

my bad !

01.25.05

09:15

02.03.05

07:17

inderjit kaur

02.04.05

06:31

This marc fellow didn't criticize Sontag as a person, merely her work. Primarily her philosophic work.

Sontag has some good stuff but I would agree that much of it is derivative and can be awfully dumb at times.

Those that criticized this guy for his "hate" might wish to stop making such moralistic judgments. For example, How do they reconcile

Sontag's "comparison of an entire race of people to cancer" to their moralistic use of the word hate toward somebody that is merely making a criticism of someone's work ? It seems to me calling an entire race of people cancer is more hateful than a criticism of a persons work.

Sontag's art is perhaps another story. An artist should be given more latitude than a philosopher and I think some of her art is "not bad". But like so many people today I don't think she created any artistic oceans.

I suspect Sontag will go down, provided she is even remembered at all, as a minor cult figure of no real significance. Maybe I am mistaken but that is how I see it.

02.20.05

02:11

This fellow didn't criticize Sontag as a person, merely her work. Primarily her philosophic work. I looked into it and it was Nietzsche's idea which was attributed to Sontag and also the quote about illness was not among her finest. But two quotes does not a philosopher make.

Those that criticize this guy for his "hate" might ask themselves how they reconcile Sontag's comparison of an entire race of people to cancer to their moralistic use of the word hate toward somebody that is merely making a criticism of someone's work ? It seems to me calling an entire race of people cancer is more hateful than a criticism of a persons work.

Sontag's art is another story. An artist should be given more latitude than a philosopher and I like some of her art although I don't think it is "great".

It often takes 20 years or more after a persons death (although not always) to be able to judge the significant of a thinker or an artist. Edgar Allen Poe was grossly misjudged by his contemporaries and it was only later that he was recognized.

Ultimately, the strength of a persons work will find its way into light. My take on Sontag is that she is a passing fad among the scribbling class and academia - Destined to last until the next fad comes along.

02.22.05

03:45

03.01.05

07:05

by Arthur C. Danto, Hal Foster, Abigail Solomon-Godeau, and Wayne Koestenbaum.

READ ON for reflections on Sontag's "achievements and legacy, which challenge us to reconsider the role of the critic today. Danto's essay, posted here, focuses on Sontag's search for 'an erotics of art. . . rather than a hermeneutics.'"

Greetings, Shlomit

03.04.05

01:35

Iván E. Egües P.

Quito - Ecuador

5 del Julio del año 2005

07.05.05

11:46