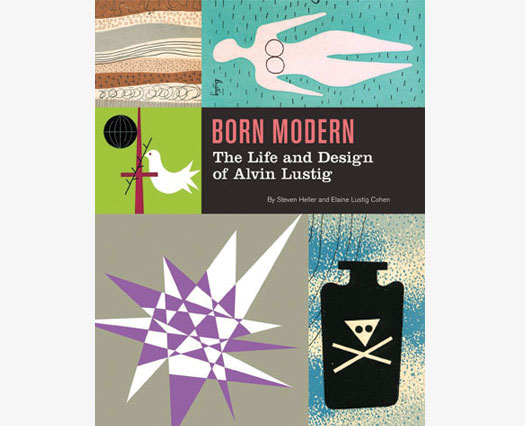

Cover of Born Modern: The Life and Design of Alvin Lustig, by Steve Heller and Elaine Lustig Cohen. Designed by Tamar Cohen. Published by Chronicle Books

In 1954, Alvin Lustig gave a lecture titled “What Is a Designer?” at the Advertising Typographers Association of America. It was one of many such talks he gave to organizations, art directors’ clubs and schools around the United States and Canada. However, this lecture was different. It was his first speech after he lost his eyesight. Yet there he stood, firmly planted on the stage, fervently spreading his gospel about the importance of good design to the world at large. Another person might have declined the invitation to speak after such a medical trauma, but Lustig was so committed to his message he couldn’t — and wouldn’t — miss the opportunity.

Lustig had a curious religious side; in fact, for a brief time in his youth he embraced Jesus and the idea of messiah, but just as quickly returned to being a cultural Jew. He possessed “a sense of order in the universe,” wrote Arthur A. Cohen, which fostered the belief that design was an essential means of making earth a better place. Since this conference was possibly one of Lustig’s last chances to take the bully pulpit, “What Is a Designer?” had an even more strident tone than earlier talks. He implored his audience to action. Addressing advertising art directors, who with few exceptions prior to the mid-’50s “Creative Revolution” did not hold truly influential positions, he urged them not to succumb to conventions, but to become “designers with a capital D.” This Modernist, holistic notion, born at the Bauhaus and other progressive academies, lay dormant with few exceptions for decades until the late twentieth century, when the so-called citizen designer emerged. Lustig’s fervency was ahead of the curve in the early ’50s.

One way to impact the world, if only in a small way, was to propagate design through writing. Lustig exhorted listeners and readers to view the commonplace in uncommon ways: In “What Is a Designer?” he explained, “design is related in some way to the world, the society that creates it. Whether you’re talking about architecture, furniture, clothing, homes, public buildings, utensils, equipment, each period of design is an expression of society, people will respond most warmly and directly to those designs which express their feelings and their tastes.” In just a few sentences, he clarified the responsibility of designers and the purpose of design, characterizing it as a noble yet profoundly misunderstood art and craft.

In his writing for trade magazines and journals, including the AIGA Journal, Design Quarterly, Publishers Weekly, Interiors and the newsletter Type Talks, utopian optimism was central to Lustig’s aims to raise the standards of design, especially graphic design. His prose, while formal and sometimes too wordy, is at once reasoned and critical. Nonetheless, he did not pull punches when the need arose, a trait that was uncommon in the overly polite design community.

In 1958, some of Lustig’s better texts were anthologized in The Collected Writings of Alvin Lustig, edited by Holland R. Melson and funded with a grant given to the Yale art department by Elaine Lustig. This small, limited-edition volume is the only collection of Lustig’s talks and essays ever published, although a few pieces have been published in larger anthologies. Through these essays, it is possible to “hear” Lustig’s thought process, although no recordings of him exist.

When Lustig started seriously writing about design in the late 1940s, only a few American designers were practicing basic journalism, while scholarly and professional criticism were virtually absent, although there were copious amounts of both in Europe. The most prolific among the American writers was the typographer and book designer William Addison Dwiggins, who coined the term “graphic designer” in an article titled “A New Kind of Printing Calls for New Design” in The Boston Evening Transcript in 1922. Industrial designers like Norman Bel Geddes and Walter Dorwin Teague were prolific and both wrote career-defining books (the former’s 1940 Magic Motorways suggests prescient guidelines for a new American infrastructure, and the latter’s 1940 Design This Day encouraged a nation emerging battered from the Depression to tap into design for strength and power). On the graphic design side, fewer designers were publishing. Paul Rand was an exception with Thoughts on Design, published by Wittenborn in 1947 (although it would be almost four decades until he published another book). A few professional “design writers” reported in professional journals or trade magazines such as Advertising Arts, American Printer, PM/AD and Print (and briefly in the lavish, short-lived Portfolio). These venues for “trade journalism,” however, lacked the rigor of art, literary, or architecture criticism. Of course, there was never an accepted vocabulary for graphic or industrial design criticism, so the language was ad hoc. Thus, it was something of an occasion when Lustig wrote about graphic design as a crucial discipline for practice and scholarship.

In his essay titled “Graphic Design” in the short-lived Design magazine, Lustig explained a rationale behind conceiving the graphic design program at the Black Mountain Summer Institute. The essay became something of a manifesto for his pedagogy. He emphasized “the fact that graphic design is slowly emerging as a serious art on its own terms.”[1] While this was implicit in essays and manifestoes issued during the ’20s and ’30s by members of the European avant-garde, it was rarely discussed in the United States. Today Lustig’s words are as familiar as they were then unexpected — and they have become something of an anthem for contemporary design writers. “The basic difference between the graphic designer and the painter or sculptor,” he wrote, “is his search for the ‘public’ rather than the ‘private’ symbol. His aim is to clarify and open the channels of communication rather than limit or even obscure them, which is too often the preoccupation of those only dealing with the personal symbol.” While he was warning designers away from self-indulgence, he also acknowledged parity between graphic and other design forms and their industrial ties. “Graphic design, like architecture, is an industrial process and demands complete mastery of all the technical conditions, as the designer depends entirely on a set of skilled workmen he has never met to carry out his plans.”

Lustig’s essays regarding pedagogy are as valuable for what they reveal about the early stages of progressive design education as they are for illuminating his own role in the process. In “Designing, A Process of Teaching,” Lustig proffers design as its own art form. “I have a great interest in painting because I think painting at this moment still carries the superior vitality,” he wrote. “Certainly the painter is doing a kind of research that the designer can’t do,” but he adds that painting has its limitations and that design, which is a more public than private activity, is becoming a venue for progressive expression. “These great private symbols which [painters] have evolved are now waiting to be projected onto the public level, and the painter confronted by these gigantic gestures, is almost powerless.” In adhering to the Modern gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art) principle, Lustig was a proponent of the idea that art for art’s sake and art for function’s sake could be one and the same.

Here he admitted that rather than maintain carefully worked theories of design, “I would reverse the process and try to track down the instinctive, the quite often unconscious development which leads one later to feel that such a theory is necessary.” In one of his most eloquent essays on the process of design — a keen example of critical analysis — he wrote: “I have found that all positions men take in their beliefs are profoundly influenced by thousands of small, often imperceptible experiences that slowly accumulate to form a sum total of choices and decisions.” In fact, this essay is an explanation of how he became a “modern” rather than a “traditional” designer. He continued: “I hope the reader will forgive me if this becomes personal, but tracing this kind of organic development is very vital.” And he went on to discuss the ability to “see’ freshly, unencumbered by preconceived verbal, literary or moral ideas... The inability to respond directly to the vitality of forms is a curious phenomenon and one that people of our country suffer from to a surprising degree.”[2]

Lustig’s designs fluidly shift from past to present. For his early “experimental” work he built upon an armature of old technologies (metal type) and techniques (neo-constructivism), which evolved through new technologies (photographic manipulations) into unprecedented styles (his own interpretation of the Modern). Toward the end of his life, his typography turned into a playful amalgam of vintage letters composed in contemporary layouts with vibrant colors. In “Personal Notes,” he wrote, “As we become more mature we will learn to master the interplay between past and present and not be so self-conscious of our rejection or acceptance of tradition. We will not make the mistake that both rigid modernists and conservatives make, of confusing the quality of form with the specific forms themselves.”

He was also concerned with the state of Modernism in the design world, and weary of the traditionalist versus Modernist wars — while at the same time he was a staunch supporter of the modern ethos. “Like all revolutionaries the modern designers have always been a little self-conscious and even defensive,” he wrote in notes for an unpublished essay on the virtues of modern printing. “Now that the battle shows signs of having been won it is time to reexamine the situation. As is always the case with revolutions, some have reversed themselves completely. A man like [Jan] Tschichold, after evolving some of the basic tenets of modern typography, has decided that he is all wrong and has reverted to a kind of static conservatism that even outdoes the traditionalists. We will not go into the psychology of the turn-coat, but it is sufficient to say that the mentality that is capable of this kind of action certainly is not an example of the deeply felt inner necessity... It is a peculiarly European performance and is a direct outgrowth of the manifesto-spawning characteristics of their art activities. It is inconceivable that a personality like Frank Lloyd Wright would suddenly announce that he had been all wrong and henceforth he will build only in the classic style.”[3] He often used simple themes like “what is modern printing?” to expound on larger design issues.

The more Lustig engaged in various disciplines in his studio, the more he wrote about subjects other than graphic design. Architecture was a significant theme, and despite his lack of architectural vocabulary, he was articulate on the subject. Various drafts of published articles and unpublished notes in his archive give voice to his interest in, and at times frustration with, contemporary architectural practice. In a short essay (perhaps notes for a lecture), he wrote about dichotomies that troubled him (and have in recent years risen to the surface of design consciousness): “Another strong line of division which has been too arbitrary has been the choice between purely esthetic gestures which pretend to ignore social consequences and architecture whose claim to worth has been based primarily on certain social attitudes ignoring a certain degree [of] refinement of design.” And in a similar text he argues on the side of modern American architecture having its own spirit: “America is a growing synthesis of extremely varied ethnic, political and religious strains and so will be her architecture... No less an American than Louis Sullivan in a lecture given in 1897 said that the destiny of American architecture will be to merge the apparently conflicting architectures of heart and mind, a fusion he pointed to that has not yet taken place in the history of man.” He was adamant in his own work, as well as his more general worldview that “America can still learn the lessons and discipline of intellectual rigor from Europe without fear of tainting or losing her on own vital character.”[4]

Ultimately, Lustig’s interest in architecture underpinned both his practice and theory of typography. In raw notes for yet another lecture, he resolutely sought to address “The relationship of the organizing principles of letterforms and organizing principles of architecture... [and] show those examples in which the letter and the building are conceived in the same terms of construction and those in which the letters have a life of their own and grow from principles quite independent of architecture.”[5] The graphic design and architecture nexus was eventually embraced by younger designers, in large part thanks to Lustig’s writing.

In May 1955, just six months before he died, Lustig submitted to Harry Ford, an editor at Alfred A. Knopf, a proposal for a monograph. “Enclosed is the précis for a book,” he wrote. “I’ve tried, as you suggested to make it rather detailed and specific although I found I didn’t have to much to say.” This last line is rather ironic given both the length of the précis and the depth of the proposal he sent to Ford on July 8. His thematic chapters/essays were decidedly progressive for American design, but consistent with European concepts. They include “The Designer in a Living Society,” “Structure and the Sense of Order,” “Private and Public Symbols,” “Design Education,” “Scale and Environment,” “Principles of Contemporary Typography,” and “An Approach to Architectural Lettering.” Subsequent correspondence with Ford and Sidney Jacobs, Knopf’s production manager, reveal that there was serious interest in doing the book. Lustig provided a “breakdown of the physical content [that] has been worked out rather carefully in relationship to the specific material and I think presents a fairly accurate picture.” After detailing his desires, Lustig notes: “This is about as specific as I can be without sitting down and actually designing the book. If we can come reasonably close to this general character I would be very pleased.” The intricate production specs Lustig proposed met with the following response from Jacobs: “I am completely confounded by the mathematics of your précis for the book you propose to do.” Discussion about the project did not go further.

The untitled monograph was never published; so we will never know how significant the book might have been in the world of design. By 1955, Lustig was garnering a sizeable amount of press (both in the trade and mainstream periodicals), so interest in a monograph was potentially high. The outline indicates that the themes elevate design and design writing to a higher level than existed at the time. The fact that the book was, in its formative stage, not solely celebrating Lustig’s achievements but also promoting good design, may have afforded this a much wider readership than typical design books.

The above text is by Steve Heller and Elaine Lustig Cohen, and is excerpted from Born Modern: The Life and Design of Alvin Lustig (Chronicle Books, 2010) and has been reprinted here with the author's permission.

Notes

1. Alvin Lustig, “Graphic Design” Design, 1946.

2. Alvin Lustig, "Design, a Process of Teaching," op. cit.

3. Alvin Lustig, undated unpublished essay. Collection of Elaine Lustig Cohen.

4. Alvin Lustig, unpublished notes, response to an article in House Beautiful.

5. Alvin Lustig, unpublished notes, undated. Collection of Elaine Lustig Cohen.

Comments [4]

12.09.10

06:43

There is much that continues to be pertinent in the 21st century, including this: "As we become more mature we will learn to master the interplay between the past and the present and not be so self-conscious of our rejection or acceptance of tradition."

I'm not so sure that we've reached that maturity at this point, but perhaps a lack of consensus adds necessary spice to our profession. I'm looking forward to seeing the new Lustig book.

12.11.10

06:35

12.12.10

10:51

12.18.10

10:06