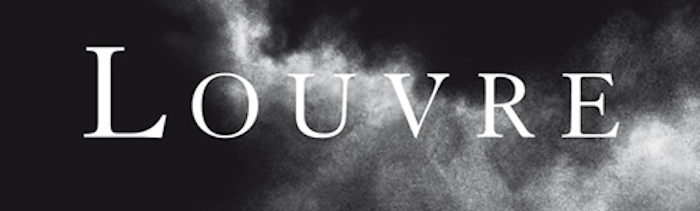

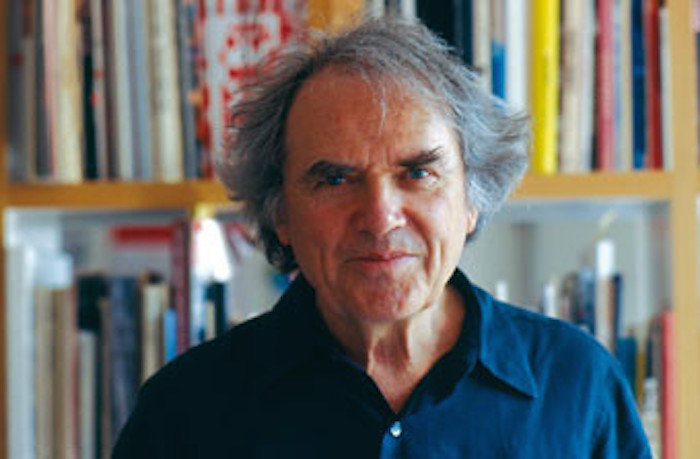

In 1992, Pierre Bernard created a logo for the Musée du Louvre. It was the closest thing to an unidentified flying object: the name of the museum was set against a black and white photograph of a cloud—a delicate patch of cirrus drifting over the Paris sky. Coming up with unusual design solutions was Pierre’s genius. Just as impressive was his ability to convince his clients to embrace visual concepts that transcended viewers’ expectations. The logo for the Louvre suggested that looking at works of art was a sublime experience—an emotion as universal as watching a sunset or marveling at the immensity of the sky.

Last month, as Pierre was fighting a losing battle against cancer, the Louvre decided to change the logo that had been its signature for more than two decades. Times are changing. Marketing concerns can no longer be ignored, and even the most prestigious cultural institutions of France must yield to it.

Pierre Bernard died yesterday, and the heartbreaking news of his untimely passing is a chilling reminder that nothing can bring back his time—a time when personal, philosophical, ethical, and political engagement had a role in shaping the way we communicate with each other. The moral stature of Pierre Bernard was his force. Once, I asked him how he had managed to “sell” the Louvre logo to the museum director. My question puzzled him. He hadn’t sold anything. He had never tried to get anyone to buy his ideas. The quiet power of his convictions was his methodology.

Pierre is best known as one of the founding fathers of Grapus, the design collective that dominated the Paris cultural scene after the student revolution of May 1968. Active between 1970 and 1990, the collective championed social conscience while at the same time conjuring up a street-inspired, rambunctious “style” whose impact has defined an entire generation of French graphic designers.

As the cohesion of the group was falling apart, Pierre Bernard began to work independently, founding the Atelier de Création Graphique, a design studio whose clients included (in addition to the Louvre) the Centre Georges Pompidou, the French national park service, and a number of other cultural institutions. He taught at the Ecole nationale supérieure des arts décoratifs (ENSAD). A member of the exclusive Alliance Graphique Internationale (AGI) since 1987, he was recognized with its prestigious Erasmus Prize in 2006.

His death makes orphans of everyone in the French graphic design community. He was our moral conscience—and an exemplary one to boot. Even though he never sold out, he was a successful practitioner of a discipline he described as “an immediate response to a perception that exists first and foremost in a social and urban context.”

His inspiration was life, ordinary life, but in all its unexpected dimensions.

Comments [7]

11.24.15

08:11

11.24.15

09:34

11.24.15

04:11

11.25.15

09:47

11.25.15

07:59

11.27.15

04:06

12.02.15

02:12