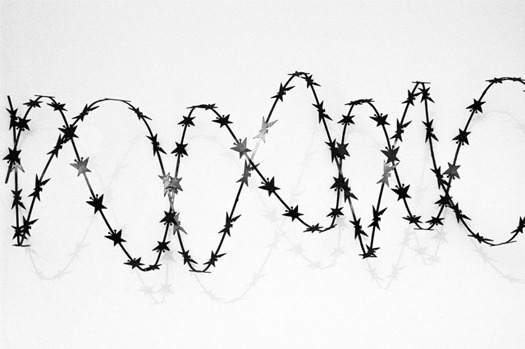

Matthias Megyeri's designs (shown above and below) "merge the need for protection with a desire for harmony and beauty".

In his new show at the German Architecture Center (DAZ) Matthias Megyeri has developed a design language for the artefacts of protection and security in public space.

Megyeri poses the question: does protection have to be inconsistent with harmony and beauty? His answer is a family of padlocks, chains, fences, and razor wire that he describes as ‘lovable objects’.

Megyeri’s work has a critical edge that was lacking in early design responses to the Age Of Fear. Entries to the Department of Homeland Security logo contest in 2003, for example, were devoid of nuance and critique.

The 2005 Computer Human Interaction (CHI) conference of 2005 was not much more questioning: It took as its theme, ‘Technology, Safety, Community’ and posed the ‘challenge for technology to make people feel safe again’.

Megyeri’s show prompted me to Google “design” and “homeland security” once again. I’ve repeated the exercise from time to time since July 2004 when the score was 600,000 — and the rate of growth never ceases to impress. Today’s score is no exception: At 12,500,000 hits it is proof, if any were needed, creative professionals remain fascinated by the design challenge of risk.

Follow That Money

To a critical or even curious person it is surely odd that the United States, which faces no military threat, spends more on its military and intelligence now than it did during the Cold War. And despite growing social precarity, total national security costs are as much as 2.5 times the baseline Defense budget and more than the combined cost of Social Security and Medicare.

This mountain of security spending by the state is stupendous enough — but it's but one part of a bigger picture. The larger security landscape also includes what David Braeber described recently as ‘the almost dazzling accumulation of private security agencies, militarized police, guards, and mercenaries‘

Corporations are leading the way. They may be slashing payrolls, and trimming worker benefits, but, as Sam Pizzigati has discovered, their spending on executive security, already high before hard times hit, is soaring.

Since 2007, Pizzigati reports, Starbucks has shelled out $1.6 million to protect CEO Howard Schultz; in 2009 alone, the Las Vegas Sands gaming giant paid $2.45 million to secure the person and property of CEO Sheldon Adelson and Oracle software has shoveled $4.6 million, over the past three years, into a “residential security program” for billionaire CEO Larry Ellison.

So: Are we safer?

Immediately after 9/11 Gregory Treverton, a risk analyst at the RAND Corporation, was asked what people could do to protect their family and home.

His response? They should do nothing. "Anyone’s probability of being killed by a terrorist today is essentially zero" he said at the time — and repeats that advice today.

Other writers have pointed out irrationalities at the heart of the security economy.

Yes, three thousand people died horribly on 9/11 — but that same number perish every single day as a result of road traffic injuries; 320 people per year drown in bathtubs.

Yes, Muslim extremists exist — but they’ve been responsible for one fiftieth of one percent of the homicides committed in the United States since 9/11.

Yes, one British nutter tried to blow up his shoes on a plane — but the number of terrorist incidents on American airliners over the last decade was one for every 16.5 million flights.

To state the obvious, security is not the objective here. Business is the issue.

A quarter of the American population is now engaged in “guard labor” for example — defending property, supervising work, or otherwise keeping their fellow Americans in line. (In Sweden, as a comparison, the guard labor share of the workforce comes in at less than half the U.S. level).

Defense and security think-tanks talk routinely these days about “the security market’s industrial base” and “the response-based nature of security contracting”.

The unique feature of this industry is its capacity to grow like topsy without providing meaningful value for money.

It’s true that some hard products are delivered by the industry — but most of the money goes on "services" and “software” — whatever that might mean. Unisys and IBM, to give two sureal exampkles, are both prime contractors for the Enterprise Acquisition Gateway for Leading Edge Solutions (EAGLE).

“Are we safer?” is probably the wrong question. As researchers in Australia have pointed out, posting a security guard at a building’s entrance enhances safety — but microscopically. The correct question is: “Are the gains in security worth the funds expended?”

It's a complicated question but the short answer is: not remotely.

To be deemed cost-effective, the Australian study found, “the industry would have to deter, prevent, foil, or protect against 1,667 otherwise successful Times-Square type attacks per year — or more than four per day”.

Otherwise stated: The security industrial complex is not selling safety, it‘s selling fear. Rather than detail the likelihood of the terrorist hazard and put it in reasonable context, officials in charge of public safety tend to focus on worst case scenarios — or, as Bruce Schneier put it, they ‘imagine the worst possible outcome and then act as if it were a certainty’.

Matthias Megyeri — Acts of Sweet Dreams Security® Until 19 May at DAZ, Köpenickerstr. 48/49, 10179 Berlin Wednesday - Sunday, 2pm - 7pm