I first came across a Polaroid camera, what I now know as a Model 95, in my grandparents' attic sometime in the mid 1970s. I must have been about seven. It was a tremendously appealing object, a machine that unfolded and had a bellows and made very satisfying clicking and snapping sounds. Unfortunately, I never got to take a picture with it. But a little more than a decade ago, after editing a book of Ed Fella's instant photos of found typography, I went online and bought my own Polaroid, an SX-70, and I was hooked. I had little sense of Polaroid's curious history, however; of the amazing technological feats that made it possible, and the company's innovative design and marketing efforts. Christopher Bonanos has rectified that with Instant, his sympathetic and beautifuly told history of Polaroid and Edwin Land, the visionary who was the company's founder and presiding genius. It is the rare design-subject book with a truly dramatic arc, and storytelling that lives up to it.

Land did not start his company with an aim of making instant pictures. His first goal was to improve auto safety by reducing glare from headlights. (Land, in his younger days, actually looked quite a bit like Ralph Nader.) As a possibly apocryphal anecdote would have it, Land's daughter prompted her father's great innovation when she asked why it took so long to develop their vacation pictures. That was his eureka moment. But Eureka moments are rare, and Land actually had quite an inspiring work philosophy. In a 1958 speech at the Polaroid Christmas party, he told his employees, "You'll be unhappy part of the day. You'll fix that by doing something worthwhile, and then you'll be happy for four hours; the next morning you'll come in unhappy, and you'll fix that by doing something worthwhile that adds on to what you did yesterday." Eventually, you end up with something wonderful, or at least that's the hope. And then the loop begins again. It's a perceptive way of thinking about work, and I think beautifully describes the process of writing. To follow is a conversation with Bonanos about his work on Land and Polaroid.

ML: Let's begin with some basics. There have been other books about Edwin Land and Polaroid, so what prompted you to undertake this one? Did you have a family history with Polaroid? Were you always a Polaroid hobbyist, or did you come across the story more recently as a journalist, and realize there was an opportunity to look at it in a new way? How long did it take?

CB: Well, it felt like a good time to tell the full story, because Polaroid film went away in 2009. All the other books have their merits, but each of them ends when Polaroid is still sailing along as a company. So I was able to get into the long decline and collapse, which makes the optimistic first half of the story change in the retelling – it adds an undercurrent of poignancy, because we all know how it's going to end.

That said, I was always bewitched by Polaroid. When I was about 14, I bought a Model 900 camera in a secondhand shop. (Three bucks.) It took Polaroid's original roll film, which was already somewhat obscure by then, and I spent a bunch of time on the phone to a Polaroid customer-service rep, trying to figure out how to use it. I came back to Polaroid photography a few times over the years, drifting in and out, the way a lot of people did. And then, when Polaroid film was discontinued altogether in 2008, I wrote a little story for New York magazine, and discovered the depth and passion of the Polaroid cult, and the story of Land and his company. So what I had found myself was a well-structured story – rise, fall, small-scale revival – and a great central character to serve as the spine. Those three things, if you're a journalist, say "there's a book in here." Plus, when there's a cult around a given subject, you have a built-in readership, which means you can get a publishing house to take you on.

ML: You introduced me to a wonderful new term: a kludge, that being a jury-rigged technical fix that gets the job done but in a sloppy and somehow unsatisfying manner. Part of the story of Polaroid is the overcoming of kludges, and of course there is a lot of scientific and technical talk in this book. Explaining its science in a compelling way was a serious challenge for Land, and I imagine it was for you, too. One of the many merits of Instant is that you manage to do this with such apparent ease (though I am sure it took considerable effort), and without dumbing the material down. I think that's something those of us who write about architecture and design are constantly fighting: a need to dig into the nitty gritty of technical detail while not losing the attention of an untrained audience. How did Land do it? How did you? Did you learn anything from him, and do you have any suggestions for the rest of us?

Edwin Land at work. Nixon asked, "How do we make more Dr. Lands?" Photo: Nan Lane Rudolph

CB: It's a great word, kludge, isn't it? (I learned it from Tracy Kidder's The Soul of New Machine, which was about Data General, another great Massachusetts tech company that fell apart in the 1990s.) I definitely sweated over the physics-for-poets passages, but I came in with a basic advantage — I have a technology background of my own. In college, I studied engineering for a couple of years before switching to the history of science, and wrote a thesis on the aesthetics of the suspension bridge. Plus my father is an engineer — he specialized in building giant magnet coils — and I grew up hearing a lot about them over dinner. So I don't scare easily when faced with a technical subject, and I really try to understand what I'm reading before I boil it down. I guess the best advice is to read everything, slowly, over and over, until you can get your arms around it. And also to be willing to sound like a fool when you ask a scientist exactly how things work.

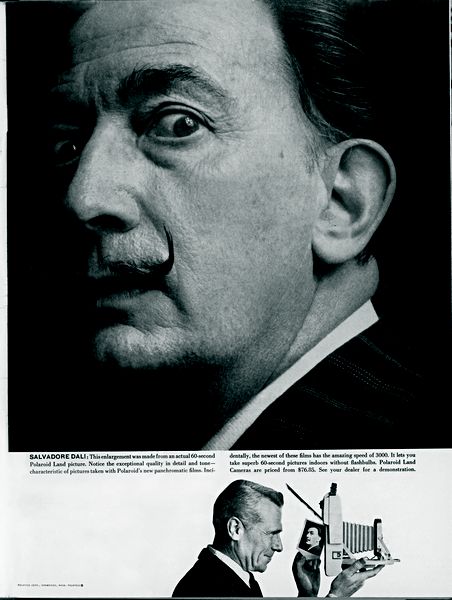

Land was the real master of explaining his science, though. He believed — correctly, I think — in the power of the dramatic demonstration, the kind that delivers an "aha!" moment. When he was trying to sell a sunglasses company on his first invention, the polarizing filter, he rented a hotel room facing the sun, and checked in with a bowl of goldfish, which he set on the windowsill. The businessmen showed up to meet him, and Land ushered them in while saying "I'm sorry for the glare. You probably can't even see the fish," and handed each of them a filter. That was a deal-maker, and also a template for his whole life. There's a great BBC film of Land in his seventies doing demonstrations with filters that illustrate his grand theory of the way color vision works, which he called Retinex.

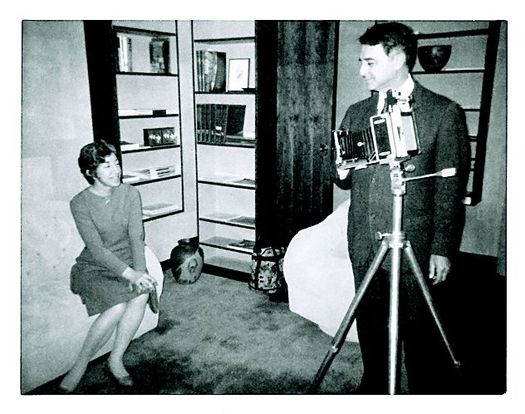

ML: I loved the goldfish anecdote. It's suggestive of the wonderful paradox or dichotomy of Polaroid. That is, a Polaroid photo is a kind of incantatory thing that magically comes to life before your eyes. But it is not magic at all, it's produced by this very tangible and tremendously alluring physical object. There is an almost sexual satisfaction in the process of taking a Polaroid picture. The locking of the camera into erect position; the click-whirr once you hit the button. Land said his camera "ejaculated" a picture. I suppose the shaking of the photograph kind of combines these two aspects, though you point out that this is actually not recommended. (Never mind OutKast.) And this raises the curious question: To what degree was the Polaroid story driven by porn.

CB: If it wasn't the first thing people figured out they could do with a Polaroid camera, it was close to the first. The Kinsey Institute, I'm told, has a bunch of Polaroid pictures in its collection — amateur stuff, from the first years of instant photography. (I haven't seen those photos, but I talked to a researcher who has, and he says they're pretty explicit.) You know, before Polaroid came along, you pretty much had to either send your film off to Kodak to be processed or build your own darkroom, and photos of a that type couldn't be sent through the mails without the risk of arrest. So a whole new world was opened up for your friendly neighborhood perv. It's said that the adoption of the VCR was largely propelled by the porn business, and it's certainly true of the Web. Porn, for better or for worse, is the killer app for a lot of technological advances.

The Polaroid Swinger, the company's 1965 attempt to capitalize on its bedroom reputation. Photo Danny Kim

One thing you just said interested me especially, though: that it's not magic. That's an important point, one that a couple of Polaroid people emphasized to me. It's fun to think of the development of an instant photo as a little trick, but what's worth remembering is that it's a product of reason and sustained hard work and hard science, not superstition. The profound thing is that we, as a species, can do this with our brains and our will — figure out how (for example) to take something that's highly light-sensitive, expose a picture on it, and then two seconds later have it pop out into the sun and stay lightproof. Most people wouldn't have the foggiest idea how to begin doing that, and Land and his crew not only figured it out--they were able to mass-produce it, in such a way that it cost less than a buck.

ML: About that crew. You portray Land as, for the most part, a wonderfully progressive and generous leader. One of the unusual things about him was his willingness to hire bright women with no scientific background and place them in key research positions. Many of Polaroid's critical scientific innovations were made by women. Yet these women were also known, albeit affectionately, as his "Princesses." And, perhaps I am wrong, but I got the impression that few of them made it to the very top of the executive ladder. Is that true? Also, how did Polaroid do with other minorities?

Land was a pioneer in hiring women to research positions. Here with artist Marie Consindas. The photo was by top Polaroid researcher Meroë Morse.

CB: Most of the women working closely with Land were scientists, and did not go into the more corporate branches of the company, like marketing or production. So they tended to stay in the labs. But they did well: the head of the black-and-white film program was a woman named Meroë Morse, and one of Land's top researchers, Vivian Walworth, was not only doing very interesting work on film emulsions and thin-film coatings but still is. It really was an organization where a female scientist had a better shot at doing interesting work than almost anywhere. As for minorities, it was a good company for its time but also capable of some big fumbles.

Land was pretty idealistic about social reform — he was a good Massachusetts liberal — and Polaroid had EOE programs and such, well before many of its corporate peers did. Then, in 1970, an employee got wind of the fact that South Africa's government was buying Polaroid film to make the passbooks it used to enforce apartheid laws. A couple of people tried to get a boycott going, and the company responded awkwardly, trying to keep its distance — putting the responsibility on an independent distributor in South Africa — and then gave a lot of money to black charities in Boston, which looked somewhat craven. The irony is that a relatively progressive company with good intentions got badly tagged for its practices, when many others were so much worse. I mean, look at a company like Coca-Cola back then, and then at Polaroid, and there's no comparison.

ML: One aspect of public relations at which Land was especially adept was in building relationships with artists. Because a Polaroid camera is a bit clumsy in the hand and hard to focus, because the saturation of the film is so idiosyncratic and rich, and because the format is so unique, Polaroid encourages, as you note, a kind of self-conscious artiness. It's amazing what a broad spectrum of artists ended up working with Polaroid. I know when I started taking Polaroids, I was influenced by Walker Evans, one of the "house" artists.

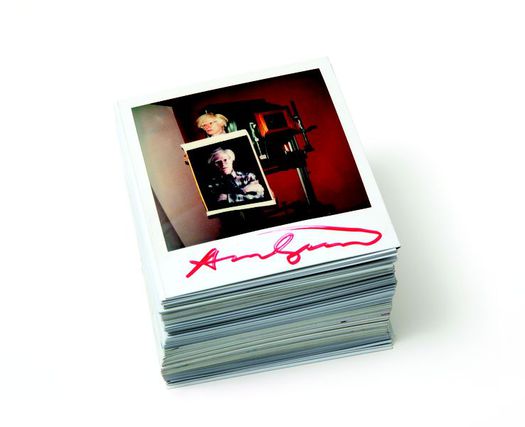

CB: That's somewhat true — though I'd say that it even more encouraged a kind of casual artless shooting that equates with what we do on social networks. The other day, I met an artist named Tom Slaughter who was a huge Polaroid user back in the eighties. We were going through his photos — he has thousands — and it's striking how much each box of them looks like an Instagram feed. They're the same kinds of casual snapshots that somehow also feel documentary and a little profound: people eating and drinking, sitting on the porch, whatever. And it's even the same square format, which is not an accident: the Instagram guys explicitly pay homage to Polaroid in their logo, and have a display of old Polaroid cameras in their offices. On the genuinely arty end of things, though, it's true that Polaroid opened up its own big niche. The spontaneity was valuable to some people, like Andy Warhol; the color was especially useful to others, like Marie Cosindas; and the unique technology was valuable to Ansel Adams and a lot of other people.

ML: Let's talk about that digital world, because the sad and ironic fact is that Land basically foresaw the very devices that would bury his own company, decades before they became a reality. It is an incredibly poignant moment, as you describe it; Land, making a presentation at a shareholders meeting, pulls a wallet out of his coat and describes a camera that one would use as often as a pen or pencil. It's impossible not to think iPhone. And we learn that Steve Jobs very consciously modeled himself after Land, who had a tremendous gift for imagining a product, and then presenting it in the most alluring manner. The book leaves you with all of these what ifs. What if Polaroid did digital. What if they did printers. From a narrative perspective, though, I feel like you got the best outcome.

Andy Warhol, an artist closely identified with Polaroid. Photo: John Reuter

CB: Really true — as I said earlier, the poignancy of it all! Because the labs were working on all sorts of digital stuff. Polaroid had prototype digital cameras in the 1980s, and backed down on the project, saying "we're not in the electronics business." What needed to be said, loudly, was that SOMEONE was going to be in that business, and it was going to destroy Polaroid's film sales either way. Probably the real heartbreaker, though, is the inkjet-printer business they considered, then rejected. Because I can understand why a company that made almost all its profits on film was leery of filmless cameras. That would've required Polaroid to become a very different operation, built on a different model. But inkjet printers are a business they inherently understood: one sale of a cheap printer means many repeat sales of expensive ink and photo paper. That's exactly how they sold cameras and film all those years, and I can almost guarantee you that the PolaJet printer you never got to buy would have been nicer than the crummy one hooked up to my computer today. Of course, it's a lot easier to say that in hindsight. And, frankly, cheap printers are themselves now a business that's looking shaky--look at Hewlett-Packard, which is circling the same drain that Polaroid fell down: lots of profitable products, but no big ideas for the next irresistible thing.

Polaroid's One Step, left. Kodak's patent violating competitor at right. Photo: Danny Kim

ML: This discussion of obsolesence inevitably brings to mind the book. I found it somehow appropriate to be reading a book about one medium that has been super-annuated (the Polaroid) in another that is on the brink (the book). Were you conscious of this as you were working? The whole Polaroid experience is a lot like the experience of the book, in that it is this very tangible object that you perform and then becomes invested with meaning. But I also have to say that Instant makes a very strong case for the book, or at least a certain kind. It's a book you want to hold in your hand and put on your shelf.

CB: It did cross my mind while I was working, but mostly for reasons that didn't involve much big thinking — it mostly happened on, you know, those late nights when you're exhausted and typing away and wondering "is anyone actually going to read this thing?" Also, as I said, I started on this project in 2008, just as the economy fell off a cliff, and for awhile I was thinking it might be a lifeline in case I got laid off. Which was not much of an idea: one part of the publishing world (magazine journalism) looked like it was caving in on itself, so I started looking into an even dicier one. Brilliant, huh?

But I'll tell you: a physical book is actually a pretty good delivery system for 40,000 words and 90 photos, which is what we ended up with here. It's light and compact and simple to navigate with low eyestrain, and the photos look great. That said, if you need it fast or don't want a brick, we're also publishing a nice Kindle edition that's really not all that different-looking inside from the printed one. And this publishing house, Princeton Architectural Press, knows how to make a book into a covetable handsome thing — I was really overwhelmed by the level of care the designers took on both the interior and the jacket. We also produced a limited edition with a slipcase and a second booklet of photos and text, exclusively sold at The Impossible Project, that's really handsome. That, I think, may be the deep future of book publishing: e-books for plain old reading, and then, for those people who do want a highly designed and pleasing object, a luxury item at a higher price point. McSweeney's is great at that, and PAPress is, and I think others may be starting to follow on the same road.

ML: I would agree on all fronts there; certainly you will get no argument as to the genius of my erstwhile colleagues on Seventh Street. And with that let me congratulate you once more on the book and thank you for taking the time for this conversation. Click whirr.

Comments [5]

10.01.12

07:11

10.05.12

12:29

10.05.12

05:32

10.17.12

11:47

10.17.12

11:48